Mahā-Moggallāna Thera

The second of the Chief Disciples of the Buddha. He was born in Kolita-

After some time, Sāriputta, wandering about in Rājagaha, met Assaji, was converted by him to the faith of the Buddha, and became a Stream-

On the day that Sāriputta and Moggallāna were ordained, the Buddha announced in the assembly of monks that he had assigned to them the place of Chief Disciples and then recited the Pāṭimokkha. The monks were offended that newcomers should be shown such great honour. However, the Buddha told them how these two had for an incalculable aeon and one hundred thousand years strenuously exerted themselves to win this great eminence under him. They had made the first resolve in the time of Anomadassī Buddha. Moggallāna had been a householder, named Sirivaḍḍha, and Sāriputta a householder, called Sarada. Sarada gave away his immense wealth and became an ascetic. The Buddha visited him in his hermitage, where Sarada and his seventy-

After the Buddha’s departure, Sarada went to Sirivaḍḍha, and, announcing the Buddha’s prophecy, advised Sirivaḍḍha to wish for the place of second disciple. Acting on this advice, Sirivaḍḍha made elaborate preparations and entertained the Buddha and his monks for seven days. At the end of that time, he announced his wish to the Buddha, who declared that it would be fulfilled. From that time, the two friends, in that and subsequent births, engaged in good deeds.²

Sāriputta and Moggallāna are declared to be the ideal disciples, whose example others should try to follow.³ In the Saccavibhaṅga Sutta ⁴ the Buddha thus distinguishes these “twin brethren” from the others: “Sāriputta is as she who brings forth and Moggallāna is as the nurse of what is brought forth; Sāriputta trains in the fruits of conversion, Moggallāna trains in the highest good. Sāriputta is able to teach and make plain the Four Noble Truths; Moggallāna, on the other hand, teaches by his psychic powers (iddhi-

Several instances are given of this special display of iddhi. Once, at the Buddha’s request, with his great toe he shook the Migāramātupāsāda, and made it rattle in order to terrify some monks who sat in the ground floor of the building, talking loosely and frivolously, regardless even of the fact that the Buddha was in the upper storey.⁸

On another occasion, when Moggallāna visited Sakka to find out if he had profited by the Buddha’s teaching, he found him far too proud and obsessed by the thought of his own splendour. He thereupon shook Sakka’s palace, Vejayanta, until Sakka’s hair stood on end with fright and his pride was humbled.⁹ Again, Moggallāna is mentioned as visiting the Brahma world in order to help the Buddha in quelling the arrogance of Baka Brahmā. He himself questioned Baka in solemn conclave in the Sudhammā-

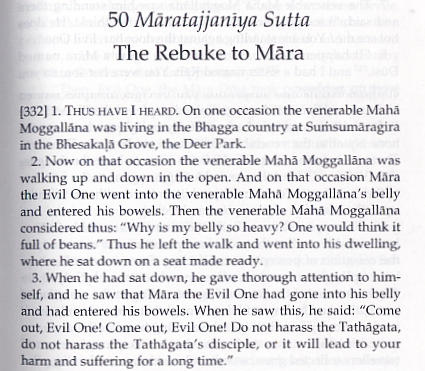

In the Māratajjanīya Sutta ¹¹ we are told how Māra worried Moggallāna by entering into his belly, but Moggallāna ordered him out and told him how he himself had once been a Māra named Dūsī whose sister Kāḷī was the mother of the present Māra. Dūsī incited the householders against Kakusandha Buddha and was, as a result, born in purgatory.

However, according to the Commentaries,¹² Moggallāna’s greatest exhibition of psychic power was the subjugation of the Nāga Nandopānanda. No other monk could have survived the ordeal because no other was able to enter so rapidly into the fourth jhāna; which was the reason why the Buddha would give permission to no other monk but Moggallāna to quell the Nāga’s pride. Similar, in many ways, was his subjection of the Nāga who lived near the hermitage of Aggidatta (q.v.)¹³ Moggallāna could see, without entering into any special state of mind, hungry ghosts (peta) and other spirits invisible to the ordinary mortal eye.¹⁴ He would visit various worlds and bring back to the Buddha reports of their inhabitants,¹⁵ which the Buddha used in illustration of his discourses. The Vimānavatthu ¹⁶ contains a collection of stories of such visits, and we are told ¹⁷ that Moggallāna’s visits to the deva worlds — e.g., that to Tāvatiṃsa — were very welcome to the devas.

Though Moggallāna’s pre-

The Buddha placed great faith in his two chief disciples and looked to them to keep the Order pure.³¹ Their fame had reached even to the Brahma world, for we find Tudu Brahmā singing their praises, much to the annoyance of the Kokālika monk.³² When Devadatta created a schism among the monks and took five hundred of them to Gayāsīsa, the Buddha sent Sāriputta and Moggallāna to bring them back. They were successful in this mission.³³ Kakudha Koliyaputta, once servant of Moggallāna and later born in a huge mind-

The love existing between Moggallāna and Sāriputta was mutual, as was the admiration. Sāriputta’s verses in praise of Moggallāna ³⁹ are even more eloquent than those of Moggallāna in praise of Sāriputta.⁴⁰ Their strongest bond was the love of each for the Buddha; when away from him, they would relate to each other how they had been conversing with him by means of the divine ear and the divine-

Moggallāna died before the Buddha, Sāriputta dying before either. The Theragāthā contains several verses attributed to Moggallāna regarding Sāriputta’s death.⁴⁶ Sāriputta died on the full-

Moggallāna’s body was of the colour of the blue lotus or the rain cloud.⁴⁹ There exists in Sri Lanka an oral tradition that this colour is due to his having suffered in hell in the recent past!

Mahā-

Footnotes

¹ For details see Pacalā Sutta, A.iv.85 f, where the village is called Kanavālamutta.

² AA.i.84 ff; Ap.ii.31 ff; DhA.i.73 f; SNA.i.326 ff; the story of the present is given in brief at Vin.i.39 ff.

³ E.g., S.ii.235; A.i.88. ⁴ M.iii.248. ⁵ BuA.31. ⁶ A.i.23.

⁷ Thag.vs.1183; he is recorded as saying that he could crush Sineru like a kidney bean (DhA.iii.212), and, rolling the earth like a mat between his fingers, could make it rotate like a potter’s wheel, or could place the earth on Sineru like an umbrella on its stand. When the Buddha and his monks failed to get alms in Verañjā, Moggallāna offered to turn the earth upside down, so that the essence of the earth, which lay on the under surface, might serve as food. He also offered to open a way from Naḷerupucimanda to Uttarakuru, that the monks might easily go there for alms; but this offer was refused by the Buddha (Vin.iii.7; Sp.i.182 f; DhA.ii.153).

⁸ See Pasādakampana Sutta, S.v.269 ff; also the Uṭṭhāna Sutta, SNA.i.336 f.

⁹ See the Cūḷataṇhāsaṅkhaya Sutta, M.i.251 ff.

¹⁰ Thag.vs.1198; ThagA.ii.185; S.i.144 f; other visits of his to the Brahma world are also recorded when he held converse with Tissa Brahmā (A.iii.331 ff; iv.75 ff; cp. Mtu.i.54 ff).

¹¹ M.i.332 ff. ¹² E.g., ThagA.ii.188 ff. ¹³ DhA.iii.242.

¹⁴ See, e.g., DhA.ii.64; iii.60, 410 f., 479; S.ii.254 ff; where he saw hungry ghosts (peta) while in the company of Lakkhaṇa; cp. Avadāna Śataka i.246 ff.

¹⁵ See also Mtu.i.4 ff. regarding his visit to the hells.

¹⁶ See also DhA.iii.291, re Nandiya, and DhA.iii.314.

¹⁷ S.v.366 f. ¹⁸ DhA.iii.227. ¹⁹ S.iv.183 ff. ²⁰ S.iv.262‑9. ²¹ A.v.155 ff.

²² S.iv.269‑80. ²³ E.g., S.iv.391 ff. ²⁴ A.ii.196 ff. ²⁵ DhA.iii.219.

²⁶ DhA.224; J.iv.265; cp. Dvy.375. ²⁷ Ibid., iv.62. ²⁸ Ibid., i.369 f; J.i.347.

²⁹ ThagA.i.536. ³⁰ DhA.i.414 f.

³¹ There is one instance recorded of Moggallāna seizing a wicked monk, thrusting outside and bolting the door (A.iv.204 ff). Once, when a monk charged Sāriputta with having offended him as he was about to start on a journey, Moggallāna and Ānanda went from lodging to lodging to summon the monks that they might hear Sāriputta vindicate himself. (Vin.ii.236; A.iv.374).

³² Kokālika had a great hatred of them — e.g., A.v.170 ff; SN., p.231 ff; SNA.ii.473 ff.

³³ DhA.i.143 ff; see also DhA.ii.109 f., where they were sent to admonish the Assaji-

³⁴ Vin.ii.185; A.iii.122 ff.

³⁵ J.i.161; see SNA.i.304 f., where the account is slightly different. There Moggallāna is spoken of as the reciter of Rāhula’s formal act of ordination (kammavācāriya).

³⁶ Thag.vss.1146‑9, 1165 f. ³⁷ Ibid., 1162, 1163, 1174 f. ³⁸ S.i.194 f.

³⁹ Thag.vss.1178‑81. ⁴⁰ Thag.vss.1176.

⁴¹ E.g., S.ii.275 ff; Moggallāna elsewhere also (S.ii.273 f) tells the monks of a conversation he held with the Buddha by means of these divine powers. For another discussion between Sāriputta and Moggallāna, see A.ii.154 f.

⁴² M.i.212. ⁴³ S.v.174 f., 299. ⁴⁴ S.v.294 f.

⁴⁵ Veḷukaṇḍakī in Dakkhiṇāgiri (A.iii.336; iv.63); and Citta-

⁴⁸ J.v.125 ff. The account in DhA.iii.65 ff differs in several details. The thieves tried for two months before succeeding in their plot and, in the story of the past, when the blind parents were being beaten, they cried out to the supposed thieves to spare their son. Moggallāna, very touched by this, did not kill them. Before attaining parinibbāna, he taught the Buddha, at his request, and performed many miracles, returning to Kāḷasilā to die. According to the Jātaka account his cremation was performed with much honour, and the Buddha had the relics collected and a Thūpa erected in Veḷuvana.

⁴⁹ Bu.i.58. ⁵⁰ J.iii.469. ⁵¹ J.i.354. ⁵² J.iii.90. ⁵³ J.ii.155. ⁵⁴ J.vi.157.

⁵⁵ J.v.192. ⁵⁶ J.iv.218. ⁵⁷ J.i.220. ⁵⁸ J.iii.543. ⁵⁹ J.iii.341. ⁶⁰ J.iv.332.

⁶¹ J.iv.69. ⁶² J.iv.314. ⁶³ J.vi.219. ⁶⁴ J.iv.297. ⁶⁵ J.vi.68. ⁶⁶ J.vi.255.

⁶⁷ J.ii.5. ⁶⁸ J.iii.193. ⁶⁹ J.vi.329. ⁷⁰ J.ii.358. ⁷¹ J.i.32. ⁷² J.v.67.

⁷³ J.v. 151. ⁷⁴ J.iii.56. ⁷⁵ J.v. 412. ⁷⁶ J.iv. 491.

Finding Footnote References

References in the notes are to the Pāḷi texts of the PTS. In the translations, these are usually printed in the headers near the spine, or in square brackets in the body of the text, thus it would be i 332 in the spine or [332] in the text. References to the Commentaries are usually suffixed with A for Aṭṭhakathā (DA, MA, SNA, etc.) but references to the Jātaka Commentary are given as J, not JA, which would normally be used, as that is reserved for the Journal Asiatic.