Mahāsi Sayādaw

Mahāsi Sayādaw

Brahmavihāra Dhamma

Download the » PDF file (1.83 Mbytes) to print your own booklets.

Contents

How to Develop Loving-kindness

Eleven Advantages of Loving-kindness

Method of Reflection to Subdue Anger

Tree Deities Terrify Five Hundred Monks

Ordinary Way of Developing Loving-kindness

How to Contemplate for Insight

Continuation of the Second Metta Sutta

How to Develop Sympathetic-joy

Developing 132 Kinds of Equanimity

Unreliable Unwholesome Things to Avoid

Wholesome Things to Investigate

Editor’s Foreword

As with my other editions of the translated works of the late Venerable Mahāsi Sayādaw, I have removed many of the Pāḷi words for the benefit of those who are not familiar with the technical terms. Where Pāḷi passages are included they are explained word by word, using the Nissaya: method. In this book, a Pāḷi word or phrase is highlighted in blue, followed by its translation in English. The entire passage is then summarised after the word-by-word translation.

The original translation was published in Rangoon in July 1985, about six years after the Sayādaw gave the Dhamma talks, which spanned a period of many weeks. To transcribe and translate many hours of tape-recordings is a huge task, but one productive of great merit as it enables a much wider audience to benefit from the late Sayādaw’s profound talks.

This edition aims to extend the audience further still by publishing the book on the Internet. Since my target audience may be less familiar with Buddhism than most Burmese Buddhists, and many may know little about the late Mahāsi Sayādaw, I have added a few footnotes by way of explanation.

References are to the Pāḷi text Roman Script editions of the Pali Text Society — in their translations, these page numbers are given in the headers or in square brackets in the body of the text. This practice is also followed by modern translations, like that below:

302 Mahāgovinda Sutta: Sutta 19 ii.224

Thus a reference to D.ii.224 would be found on page 224 of volume two in the Pāḷi edition, but on page 302 of Maurice Walshe’s translation. It would be on a different page in T.W. Rhys David’s translation, but since the Pāḷi page reference is given, it can still be found. In the Chaṭṭha Saṅgāyana edition of the Pāḷi texts on CD, the references to the pages of the PTS Roman Script edition are shown at the bottom of the screen, and can be located by searching.

I have attempted to standardise the translation of Pāḷi terms to match that in other works by the Sayādaw, but it is impossible to be totally consistent as the various translations and editions are from many different sources. In the index you can find the Pāḷi terms in brackets after the translations, thus the index also serves as a glossary.

Bhikkhu Pesala

September 2021

Translator’s Preface

Translator’s Preface

This “Brahmavihāra Dhamma” expounded by the Venerable Mahāsi Sayādaw, Aggamahāpaṇḍita reveals the systematic method of developing loving-kindness, etc., towards all beings and the way to lead a Life of Holiness. The style of presentation and the informative material contained therein stand witness to the depth and wealth of mature spiritual and scriptural knowledge of the eminent Author. The warmth and sympathetic understanding of the human nature with which the author is moved, reflects the noble qualities of a true disciple of the Buddha who was committed to the weal of all living beings, and who had throughout his lifetime from the time of His Supreme Enlightenment, devoted his Compassionate skill to the aid of others for their emancipation from the woes, worries and sufferings.

A careful reading of this Dhamma followed by an unfailing practice of meditation that has been clearly explained in this discourse will, I believe, amount to inheriting a fortune in the shape of happiness in the present lifetime as also the spiritual attainment.

As a world religion, Buddhism has been a guiding force to human civilization and to all mankind who are in misery. Life is full of suffering, and what seems pleasurable is, in reality, miserable. It was only after the appearance of Buddhism, which inculcates moral discipline and loving-kindness, that the people find a happier and more peaceful world. The way to cultivate loving-kindness and compassion (karuṇā) has been vividly shown in this Brahmavihāra Dhamma, apart from other fine qualities that one should possess and practise for one’s own benefit and that of others. Full instructions are given in this teaching to develop noble practices — particularly the four Brahmavihāra: loving-kindness, compassion, sympathetic-joy, and equanimity according to what was taught by the Buddha in a subtle and profound way with Great Compassion flowing freely towards all living beings. The Buddha could see how all beings are suffering and bearing the burden of their aggregates as long as they are drifting in the current of saṃsāra. The Dhamma teaches us to have compassion for all others in distress, from minute insects to enormous mammals. The Venerable Mahāsi Sayādaw has elucidated this to remove the dust from our eyes to discern the truth.

This teaching is enriched with a number of anecdotes that lucidly illustrate the value of developing loving-kindness, compassion and sympathetic-joy, and also how to control anger, avoid envy, practise patience and self-reliance and other virtues. It has been emphasized that human life is vulnerable to pain and suffering. Life is a process of change from the simple to the complex, birth to death, from beginning to end. Nothing ever remains the same in a person, which is composed of mind (nāma) and matter (rūpa), which are arising and vanishing at every moment of seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, touching, and thinking. The appearance and disappearance of vibrating manifestations are the becoming and cessation process of mind and matter, which are transient by nature. This fact of impermanence brings in its wake discomfort, pain, illness, and unhappiness, because what is erroneously considered as joy and pleasure are, in fact, pleasant feeling (sukha vedanā). The Buddha taught that a person who is undisciplined in morality will lack wisdom, and in consequence, even a trivial evil committed will lead to a state of misery. The Buddha taught us the way to our own salvation, i.e., to practise nobly and diligently to get rid of all suffering. The Buddha could only teach us the way to happiness. Purity and impurity belong to oneself, no one can purify another,” said the Buddha. This brings us to the law of kamma. We are the heirs of our own kamma, good and bad actions that we did in the past, and that we are doing now. In the matter of developing compassion towards a being who is suffering, and in extreme misery beyond succour, one will have to nurture a feeling of indifference (upekkhā). In essence, it is to view the kamma of that being as his own personal property (kammassakā). Good kamma produces good, and bad kamma produces evil. For example, generosity yields wealth, morality leads to rebirth in noble families and in states of happiness, anger causes ugliness, and so on. These have been shown citing relevant stories, which are authentic as taught by the Buddha.

Rare indeed is this Dhamma which has been so elaborately expounded by the author, the Venerable Mahāsi Sayādaw that our heartfelt gratitude goes to the Sayādaw, and also to U Thein Han, a retired judge and Executive Member of this Buddha Sāsanānuggaha Organization, for his pains in tape recording this noble Dhamma taught by the Venerable Mahāsi Sayādaw for sixteen times to cover the subject fully. These recordings were transcribed, and the manuscript was given to the Sayādaw for scrutiny, rewriting, and approval before the final draft went to the Press.

Life has been described as a continuous becoming (bhava) like a wheel moving on and on in the wilderness of saṃsāra. One is born, one grows up and suffers, and eventually dies to be reborn and continue the endless journey in existence. The Buddha pointed out that insight can be gained only by attaining morality (sīla), concentration (samādhi), and wisdom (paññā) through cultivating the Noble Eightfold Path. Wisdom constitutes a great accomplishment for one who aspires to know the three characteristics by contemplation and noting, which will finally lead to complete liberation from suffering after attain the knowledge of the Path and its Fruition. The Venerable Mahāsi Sayādaw has given us guidelines to achieve that wisdom by the practice of insight meditation (vipassanā) even while developing loving-kindness, compassion, etc. The impermanence of all things is evident, but when we are young, we were only vaguely aware of this. Due to lack of wisdom, health and vigour act conceal the burdens of life. As we grow older, with grey hairs and other signs of decay, we come to see what is actually happening to us in its true perspective, and the significance of the ceaseless change occurring in and around us. The Buddha’s teaching is as vital and relevant today as it was when he lived centuries ago.

I have translated this wonderful Dhamma with as much scholarly accuracy as I could, and with my humble spiritual perceptiveness that is within my practical knowledge of the Dhamma that I have been able to acquire under the guidance of my spiritual teachers. May this humble work contribute towards a wider knowledge of the Dhamma and a deeper appreciation of the morality of Buddhism, which is highly pragmatic. May the constant practice of the Dhamma along the lines indicated in this Dhamma teaching prevent unwholesome deeds and ultimately destroy all the fetters that keep us away from our final goal of nibbāna.

Min Swe (Min Kyaw Thu)

Secretary

Buddha Sāsanānuggaha Organization.

February 5, 1983

Brahmavihāra Dhamma

Brahmavihāra Dhamma

Part One

Namo Tassa Bhagavato Arahato Sammāsambuddhassa

The Meaning of Brahmavihāra

Today is the full-moon day of July, 1327 BE.¹ Beginning from today, I will talk on the Brahmavihāra Dhamma. In the compound “Brahmavihāra,” the word “Brahma” means “Noble.” This word, if properly pronounced in Pāḷi should be pronounced “Birahma.” In Burmese, it is spoken with a vocal sound as “Brahma.” This can be easily understood. The word “vihāra” conveys the meaning of “dwelling,” “abiding,” or “living.” Hence “Brahmavihāra” conveys the meaning of “Noble Living,” or “Living in the exercise of good-will.”

When analysed, the expression “Brahmavihāra” includes loving-kindness (mettā), compassion (karuṇā), sympathetic-joy (muditā), or rejoicing in their happiness or prosperity of others, and equanimity (upekkhā), or indifference to pain and pleasure. These are the four kinds of Brahmavihāra. In the Mahāgovinda Sutta ² it is referred to as “Brahmacariya.” Therefore, Brahmavihāra Dhamma is commonly called “Brahmacāra Dhamma.” Brahmacariya means chastity or living the holy life. Therefore this can also be called Brahmacāra Dhamma from now onwards.

In the Abhidhamma, the Brahmavihāra Dhamma is referred to as illimitable (appamaññā), a term derived from the meaning “infinite” or “boundless.” It is called “illimitable” because, when developing loving-kindness, it should be practised with unlimited friendliness towards all living beings.

Analysis of the Meaning

Among the four kinds of Brahmavihāra Dhamma, mettā means loving-kindness, karuṇā means compassion, muditā means sympathetic-joy, and upekkhā means equanimity. Of these four meanings when translated into Burmese, only the meaning of the word “compassion” is clear and precise without mingling with any other sense. The term “love” may convey the sense of clinging attachment with passion (rāga), or sexual desire. Joy also concerns rejoicing for fulfilment of one’s own desires, besides those connected with Dhamma. “Indifference” covers various mental attitudes. As such, if the meanings of the terms: “mettā,” “muditā,” and “upekkhā” are rendered in Burmese as “love,” “joy” and “indifference,” it might convey different shades of meaning. It would be more obvious if they are expressed in Pāḷi usage, as mettā bhāvanā, karuṇā bhāvanā, and upekkhā bhāvanā. I will use Pāḷi, which is clearer for the purposes of this Dhamma talk.³

Meditation on loving-kindness (mettā bhāvanā) just means developing thoughts of loving-kindness towards others. Even if a thought occurs wishing prosperity to others, it is just a virtuous thought. What is meant by meditation on compassion (karuṇā bhāvanā) is developing compassionate feelings towards other beings. Ordinarily, if one feels compassion for others, wishing them to escape from suffering, it is a virtuous thought of compassion. Sympathetic-joy (muditā) means joy or rejoicing with others in their continued happiness and prosperity. Equanimity (upekkhā) is a feeling of indifference with no concern or anxiety regarding other’s happiness or sorrow, having a neutral feeling thinking that things inevitably happen according to the law of kamma, as the consequence of wholesome or unwholesome deeds. Of these four kinds of Brahmavihāra, first I will deal with the development of loving-kindness.

Making Preparations for Meditation

In the Visuddhimagga, before explaining how contemplation should be done on the earth device (pathavī kasiṇa), the subject of preliminary arrangements (parikamma) is elaborated exhaustively. In brief, priority should be given to the proper observance of morality, and then to settle anything that may give rise to obstructions (palibodha), leading to anxiety regarding one’s residence. The next point is to accept with confidence the instructions given relating to the method of developing meditation on loving-kindness, which one intends to take up from a well-qualified meditation teacher (kammaṭṭhānācariya). This is the method I am now going to prescribe and teach. It is necessary to stay in an appropriate monastery, or better, a retreat centre, and settle all minor matters such as shaving the head or cutting the finger nails. Take a brief rest after meals to avoid sluggishness or inertia. Then after finishing any chores, choose a quiet, solitary place, and take up a sitting posture that is comfortable.

Crossed-legged Sitting Posture

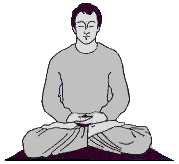

Sitting comfortably means to find a way of sitting that one can maintain for a long time without interrupting one’s meditation. To begin training, the best way is to sit erect and cross-legged. There are three sitting postures. 1) That seen in most Buddha statues. This is not easy for most people.

Sitting comfortably means to find a way of sitting that one can maintain for a long time without interrupting one’s meditation. To begin training, the best way is to sit erect and cross-legged. There are three sitting postures. 1) That seen in most Buddha statues. This is not easy for most people.

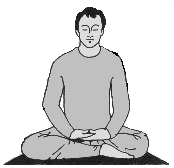

2) The way that nuns used to sit, without interlocking the legs. This position is most comfortable for many people. It keeps the legs parallel while sitting without pressing one against the other. It may be easiest since this posture does not block the flow of blood through the veins.

2) The way that nuns used to sit, without interlocking the legs. This position is most comfortable for many people. It keeps the legs parallel while sitting without pressing one against the other. It may be easiest since this posture does not block the flow of blood through the veins.

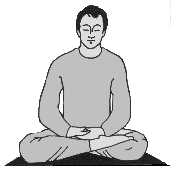

3) Sitting with half the length of the legs crossed. Any one of these three sitting postures may be chosen, whichever suits you the best. Women may sit as they please. The sitting posture as stated is required only at the initial stage of meditation. Thereafter, sitting postures with knees up or with legs stretched may be taken up according to circumstances.

3) Sitting with half the length of the legs crossed. Any one of these three sitting postures may be chosen, whichever suits you the best. Women may sit as they please. The sitting posture as stated is required only at the initial stage of meditation. Thereafter, sitting postures with knees up or with legs stretched may be taken up according to circumstances.

Meditate in All Four Postures

Meditation can be done while walking, standing, sitting, or lying down, which are the four usual postures. It is clear that meditation exercises can be done by adopting any of the four postures as stated in the Metta Sutta: “Tiṭṭhaṃ caraṃ nisinno vā, sayāno yāvatāssa vitamiddho, etaṃ satiṃ adhiṭṭheyya.” The meaning of this phrase is:

Tiṭṭhaṃ: either in the act of standing, ciram: or in the act of walking, nisinno vā: or while sitting, sayāno: or while lying down, yāvatā: for the duration of that period, vitamiddho: the mind will be free from sloth or sleepiness, assa: and it will so happen, yāvatā: for that particular length of time, etaṃ satim: this practice of mindfulness that arises with loving-kindness, adhittheyya: should be developed by fixing the mind upon it and letting oneself remain in this state of mind.

It has been clearly instructed to contemplate and note by way of assuming the four usual postures not only in respect of meditation on loving-kindness, but also in regard to practising mindfulness for insight (satipaṭṭhāna vipassanā) relating to which it has been taught as “when walking, he knows that he is walking (gacchanto vā gacchāmī’ti pajānāti),” and so forth. Hence, although instructions have been given to take up a cross-legged sitting posture at the initial stage of meditation, all four postures can be adopted as appropriate in developing meditation on loving-kindness. The essential point is to develop loving-kindness on all occasions, continuously, leaving aside about four to six hours at night for sleep. When going to bed at about 9:00 or 10:00 p.m., while lying in bed and before falling asleep, it should also be developed.

Reflect on the Faults of Anger

After taking up the cross-legged posture, the faults of anger or malice and the advantages of patience should be imagined and reflected on. If these have been already reflected upon earlier, it would be sufficient. This was taught because benefits will accrue from such reflection, but it is not essential. If practised with firm faith and enthusiasm, beneficial results will be obtained. Nonetheless, if one is going to undertake any kind of work, there may be things that should first be reflected upon or considered. Rejection can be done only if one sees the fault. For example, in the case of a person sweeping and cleaning a room with a broom, he or she would pick up and throw away scraps of paper, cloth, or broken pieces of wood if they are considered to be worthless trash. If such trash is kept or put aside in a corner, the room will not be free from rubbish. In the same way, if the fault of anger is not perceived, one is likely to accept that anger without rejecting it. There is every possibility that such a state of affairs would prevail.

For instance, people who bear a grudge against someone or have a grievance against others for something done to their detriment, may be said to be harbouring anger or malice as a close friend. An aggrieved person may feel sore or bitter even if others try to appease his anger by consoling him with kind words. If entertaining such brooding resentment, he might even become infuriated at these attempts to reconcile him. Moreover, it is likely that he would blame them for interfering. This resembles a person who keeps a venomous viper in his pocket, by keeping the anger through not realising the dangers of it. To reject the anger, one should reflect upon the faulty nature of anger and malice. The reflection to be done according to the texts is as follows:

At one time, on being asked by a wandering ascetic by the name of Channa,⁴ “For what kind of danger inherent in passion (rāga), anger (dosa), and delusion (moha), has it been taught to reject them?” Venerable Ānanda replied:

Āvuso: Friend Channa, duṭṭho: a vicious person who is bearing ill-will or becoming angry, dosena abhibhūto: being overwhelmed with anger, overpowered by anger or resentment, pariyādinacitto: which has used up or erased all noble or virtuous thoughts, without goodwill because of anger, attābyāpādhayā pi ceteti: plots to cause his own misery and, parabyāpādhayā pi: plots to cause misery to others and, ubbhayabyāpādhāya pi ceteti: plots to cause misery to both. … Kāyena: physically, duccaritaṃ: evil deeds, such as killing, carati: are committed, vācāya: verbally, duccaritaṃ: evil deeds, such as uttering abusive words, mānasa: and mentally, duccaritaṃ: evil deeds such as wishing others’ ruin or destruction of life, property, and so on.

In essence, the method is to reflect and exercise restraint based upon this teaching. By allowing aggression to arise, it is obvious that one becomes miserable. Any feelings of joy or happiness that he previously had immediately disappear. Mental distress occurs, which changes his demeanour to become grim due to his unhappiness. He becomes agitated, and the more furious he becomes, the more he is distressed and embarrassed both physically and mentally. Anger may incite him to commit murder or utter obscene words. If he reflects on such evil deeds, he will at least feel remorseful and humiliated by being conscious of his own fault. If he has committed a crime, he will definitely suffer at once by receiving due punishment for his crime. Furthermore, in his next existence he can descend to the lower realms (apāya) where he will have to undergo immense suffering and misery. This is just a brief description of how anger will bring dire consequences. Such incidents can be personally experienced and known merely by retrospection.

Misery caused to others by anger is more obvious. Making others unhappy by word of mouth is common. A person who is railed at may be very upset and suffer mental anguish. An angry mood may deteriorate to the extent of killing others or causing them severe mental suffering. Even if there is no terrible consequence in the present life, an angry person will be reborn in the lower realms in his future existences. If he is reborn in the world of human beings by virtue of his wholesome kamma, he will suffer from a short life, many diseases, and ugliness. Anger cuts both ways endangering both the person who is angry and the victim. I do not need to say any more about reflection on the faults of anger — I should use the remaining time to explain how loving-kindness can be developed.

Benefits of Patience

Next, in the matter of reflecting on the merits or fruits of patience (khantī) it is a mental quality opposed to anger. In other words it is the absence of anger (adosa). It is similar in essence to loving-kindness. Particularly, patience endures any kind of provocation and remains calm without anger or evil deeds. Loving-kindness is more extensive in meaning than patience. It embodies the quality of goodwill, rejoicing with others’ happiness. The advantages of patience have been described in the Visuddhimagga ⁵ as: “Khantī paramaṃ tapo titikkhā,” which means “Patience is the highest austerity.” It is the noblest and pious practice of virtue. “Khantibalaṃ balānīkaṃ” means that since patience has its own strength, it should be understood as taught by the Buddha that the beneficial fruits of patience by symbolising the attributes of a noble person — a Brahmaṇa — have the force or strength that is patience. What is meant by this is that the strength or vigour of patience that is capable of preventing anger resembles an army, which is capable of defending against an enemy. The Buddha has, therefore, taught that a person who is equipped with the strength of patience is a Brahmaṇa, a Noble One.

The gist of the Pāḷi phrase, “Sadatthaparamā atthā, khantyā bhiyyo na vijjati” ⁶ is one’s own benefit is the noblest, and the best is the beneficial results of forbearance or patient endurance. The advantages of patience should be realised as stated by Sakka, cited above.

As stated in the foregoing passages, patience is the noblest and best practice. It is noble and admirable because one who has patience will be able to tolerate criticism or irritating remarks, which would ordinarily incite a retort or refutation, and by virtue of this noble attribute, one will earn the respect and approval of others. He will receive help and assistance when occasion arises and can bring about greater intimacy between oneself and others. Nobody would hate a patient person. These benefits are quite conspicuous. If retaliation is made against any verbal attacks, hot controversy will ensue between the two parties and quarrels will break out. Feelings of hatred and animosity will creep in and the parties may become antagonistic to one another with malice and become enemies for life. If tolerance or patience is not practised, one will be inclined to cause harm to another, maybe, throughout one’s lifetime. If, however, patience is cherished and nurtured, it would bring many benefits. This can be known clearly by retrospection. Hence, the Blessed One prescribed in the Ovāda Pātimokkha:⁷ “Khantī paramaṃ tapo titikkhā nibbānaṃ paramaṃ vadanti Buddhā,” as mentioned earlier.

Nibbānaṃ paramaṃ: the noblest and highest goal of nibbāna. This was taught by the Buddha because all practices for the cultivation of merit can be carried out successfully only if there is patience. When donation is offered on a magnificent scale with great generosity, it needs great patience. To observe morality a person needs to practise patience, and in practising meditation, patience is also vital. All kinds of physical discomfort and pain will have to be tolerated, so only by contemplating and noting with patience, can concentration and insight-knowledge be gained. If one change one’s posture frequently due to discomforts such as stiffness, heat, and pain, it will be difficult to gain concentration. This makes it unlikely that insight-knowledge would arise. Only if one contemplates and notes with patient endurance can concentration develop, then special knowledge of the Dhamma leading to knowledge of the Path and its Fruition (magga-phala-ñāṇa), can be realised. Thus, it is said that patience is the noblest and highest practice.

The saying, “Patience leads to nibbāna,” is most appropriate. In practising for the fulfilment of the ten perfections (pāramī), it can be fully achieved if patience is applied. Among these perfections, determination, exertion, and wisdom are proximate causes for the attainment of nibbāna. Only if relentless and persistent effort is made as originally intended to reach nibbāna with a firm determination. Insight-knowledge and path knowledge will be fully accomplished. If diligently practised with patience, Arahantship will be attained. An Arahant is said to be a noble Brahmaṇa who is fully endowed with the strength of patience. That is what the Buddha has said.

Patience is a noble practice that can lead to nibbāna. When developing loving-kindness, practice of patience is essentially fundamental. Only in the absence of ‘anger’, and by practising patience, mindfulness on loving-kindness will become developed. This is the reason why it has been instructed to reflect upon the advantages of patience prior to developing loving-kindness.

How to Develop Loving-kindness

How to Develop Loving-kindness

When developing loving-kindness meditation, keep the mind on all human beings or all living beings, who may be seen, heard, or visualised. The way of developing with feelings of benevolence as stated in the Pāḷi texts and Commentaries, which say, “May they be happy (sukhitā hontu),” or “May all beings be blessed with happiness (sabbe sattā bhavantu sukhitattā).”

Whether one is in one’s own room, or whether one is moving about or working, if a person or any living being is seen or heard, loving-kindness should be developed with a sincere and sympathetic feeling as: “May he be happy! May he be blessed with happiness!” Similarly, on entering a large gathering, keep the spirit of loving-kindness in your heart, wishing, “May all beings be happy.” This is an easy and excellent practice since everyone wants to be happy. This method of developing loving-kindness is the mental kamma of loving-kindness (mettā mano kamma). At the moment when monks and laity are paying homage to the Buddha, they may develop loving-kindness by saying, “May all beings be free from enmity (sabbe sattā averā hontu).” It is the vocal kamma of loving-kindness (mettā vacī kamma),” as the feeling of loving-kindness is expressed verbally.

Besides developing loving-kindness mentally and verbally, special care should be taken to render physical assistance to others whenever possible, to make them feel happy. It would be meaningless to cultivate loving-kindness, if one caused misery to others physically, verbally, or mentally. It is therefore essential to do good to others, and by doing so, the act of developing mindfulness on loving-kindness may be said to be effective. For instance, while loving-kindness is radiated from his heart to a person who is coming face to face with him in a narrow lane wishing him happiness, it would also be necessary to give way to him, if he is worthy of respect. Such behaviour would then amount to honouring him with a virtuous thought and would be in tune with one’s inner feeling of loving-kindness. One who develops loving-kindness while travelling, would make room for fellow-travellers who may be looking for accommodation in the same carriage, provided of course, that there is space. He should assist others as far as possible if he happens to find them burdened with a heavy load. In connection with business affairs, it amounts to exercising loving-kindness by instructing another person in matters with which he is not acquainted, speaking gently and kindly, offering a warm reception with a graceful gesture and a smiling face. One should help a person to the best of one’s ability. These are genuine manifestations of loving-kindness. To speak kindly is the vocal kamma of loving-kindness; giving physical help to others is the physical kamma of loving-kindness.

Radiation of Loving-kindness

When it is stated in the Paṭisambhidāmagga that 528 kinds of loving-kindness are developed, it refers to the way of developing loving-kindness by those who have achieved absorption. Nowadays, the traditional practice is for monks to develop loving-kindness by recitation for the achievement of merits and perfections. The Pāḷi formula usually recited is the same as that learnt by heart by the majority of lay people. I will first recite that formula in Pāḷi for the purpose of categorisation and explanation.

Sabbe sattā, sabbe pāṇā, sabbe bhūtā, sabbe puggalā, sabbe attabhāvapariyāpanṇā.

These five phrases denote all sentient beings without distinction and limitation. Herein, the expressions: sabbe sattā: all beings, sabbe pāṇā: all who breathe, sabbe bhūtā: all who are born, sabbe puggalā: all individuals, and sabbe attabhāvapariyāpānnā: all those who have aggregates, convey the same meaning. Each expression refers to all beings.

“Sabbā itthiyo: all women,⁸ sabbe purisā: all men,⁹ sabbe ariyā: all noble ones, sabbe anariyā: all ordinary individuals, sabbe devā: all celestial beings, sabbe manussā: all human beings, sabbe vinipātikā: all beings in the lower realms (apāya). These expressions denote the seven different types of beings: the male and female genders, noble ones (ariya), and ordinary individuals (puthujjana), and three classes of beings: celestial beings, human beings, and beings in the lower realms.

Loving-kindness that is developed radiating towards the seven species separately and individually, identifying them in their respective types is known as specified loving-kindness (odhisa mettā). The first five phrases earlier stated, having no limitations with reference to all beings, is called universal loving-kindness (anodhisa mettā), which means loving-kindness without any distinction or limit.

In developing loving-kindness, these two groups forming twelve verses should be recited verbally or mentally in combination with the four phrases: “May they be free from enmity (averā hontu),” “May they be free from mental distress or suffering (avyāpajjhā hontu),” “May they be free from bodily suffering or injury (anighā hontu),” “May they keep themselves happy and carry the burden easily (sukhi attānaṃ pariharantu).” The last phrase conveying goodwill, “May they keep themselves happy and carry the burden easily,” is very significant and meaningful. All beings are prone to external dangers of all sorts. There are also internal dangers of diseases and painful feelings in the body. Moreover, for the sake of one’s own good health and proper livelihood, everything possible should be done and achieved without fail. Only when free from these dangers, and when life’s necessities are sufficient, then happiness could be gained both physically and mentally. If the burden can be carried easily, it can be said to be satisfactory from the point of worldly affairs. That is why development of loving-kindness should be seriously made with a benevolent frame of mind by uttering the words, “May they keep themselves happy and carry the burden easily.”

If loving-kindness is developed saying, “May all beings be free from enmity,” etc., which comprises five phrases of universal loving-kindness combined with the above four phrases for developing loving-kindness, there are twenty ways of developing universal loving-kindness.

Further, if development of loving-kindness is practised saying, “All women,” etc., comprising seven phrases of specified loving-kindness combined with the above four phrases, “May they be free from enmity,” there are twenty-eight ways of developing specified loving-kindness. Adding these to the twenty ways of developing universal loving-kindness, the total is forty-eight. Developing loving-kindness meditation without specifying the direction is called loving-kindness with unspecified direction (disa anodhisā mettā).

Similarly, developing loving-kindness towards all beings living in the East ¹⁰ (puratthimāya disāya), as “May all beings in the East be free from enmity,” would total forty-eight. Likewise, the remaining cardinal compass points: the West, the North, the South, the South-east, the Northwest, the North-east, the South-west, the Nadir (heṭṭhimāya disāya) and Zenith (uparimāya disāya): when multiplied by the ten directions will total 480. This way of developing directional loving-kindness, is known as specified directional loving-kindness (disā odhisa mettā). If this 480 is added to the 48 of loving-kindness with unspecified direction, the total will be 528 kinds of loving-kindness.

To summarise: the five hundred and twenty-eight kinds of loving-kindness: let us develop loving-kindness by reciting as follows:

1. “May all beings be free from enmity,” “May they be free from mental distress or suffering,” “May they be free from bodily suffering or injury,” “May they keep themselves happy and carry the burden easily.” (4 kinds)

2. “May all those who breathe be free from enmity,” “May they be free from mental distress or suffering,” “May they be free from bodily suffering or injury,” “May they keep themselves happy and carry the burden easily.”(4 kinds).

After the recitation of the words, “May they be free from danger” in the course of developing loving-kindness, the mind that concentrates and the voice of utterance immediately cease. This cessation of mind and matter must also be contemplated. If such contemplation is done, tranquillity and insight are developed in pairs. The continuous contemplation of tranquillity and insight in pairs is called “yuganaddha vipassanā.” Let’s recite and develop loving-kindness by applying this method of ‘yuganaddha.’

3. “May all those who are born be free from enmity,” “May they be free from mental distress or suffering,” “May they be free from bodily suffering or injury,” “May they keep themselves happy and carry the burden easily.” (4 kinds)

4. “May all individuals be free from enmity,” “May they be free from mental distress or suffering,” “May they be free from bodily suffering or injury,” “May they keep themselves happy and carry the burden easily.”(4 kinds)

5. “May all those who have aggregates be free from enmity,” “May they be free from mental distress or suffering,” “May they be free from bodily suffering or injury,” “May they keep themselves happy and carry the burden easily.” (4 kinds, total = 20).

1. “May all women be free from enmity,” “May they be free from mental distress or suffering,” “May they be free from bodily suffering or injury,” “May they keep themselves happy and carry the burden easily.” (4 kinds)

2. “May all men be free from enmity,” “May they be free from mental distress or suffering,” “May they be free from bodily suffering or injury,” “May they keep themselves happy and carry the burden easily.”(4 kinds)

3. “May all Noble Ones be free from enmity,” “May they be free from mental distress or suffering,” “May they be free from bodily suffering or injury,” “May they keep themselves happy and carry the burden easily.” (4 kinds).

4. “May all ordinary individuals be free from enmity,” “May they be free from mental distress or suffering,” “May they be free from bodily suffering or injury,” “May they keep themselves happy and carry the burden easily.” (4 kinds)

5. “May all celestial beings be free from enmity,” “May they be free from mental distress or suffering,” “May they be free from bodily suffering or injury,” “May they keep themselves happy and carry the burden easily.” (4 kinds)

6. “May all human beings be free from enmity,” “May they be free from mental distress or suffering,” “May they be free from bodily suffering or injury,” “May they keep themselves happy and carry the burden easily.” (4 kinds)

7. “May all beings in the lower realms be free from enmity,” “May they be free from mental distress or suffering,” “May they be free from bodily suffering or injury,” “May they keep themselves happy and carry the burden easily.” (4 kinds: total = 28 kinds).

These are the twenty-eight kinds of specified loving-kindness. If these are added to twenty kinds of universal loving-kindness mentioned previously, it would total 48 kinds of loving-kindness. Thereafter, let us recite and develop mindfulness on loving-kindness in the following way beginning with the East, each directional phase having 48 kinds. This way of developing loving-kindness is acceptable to every Buddhist. It is easy to do, and even those who have little knowledge can understand. Let’s begin reciting.

1. “May all beings in the East be free from enmity,” “May they be free from mental distress or suffering,” “May they be free from bodily suffering or injury,” “May they keep themselves happy and carry the burden easily.”

“May all those who breathe in the East be free from danger …

“May all who are born in the East be free from danger …

“May all individuals in the East be free from danger …

“May all who have aggregates in the East …

“May all women in the East be free from danger …

“May all men in the East be free from danger …

“May all Noble Ones in the East be free from danger …

“May all ordinary individuals in the East be free from danger …

“May all celestial beings in the East be free from danger …

“May all human beings in the East be free from danger …

“May all beings of the lower realms in the East be free from enmity,” “May they be free from mental distress or suffering,” “May they be free from bodily suffering or injury,” “May they keep themselves happy and carry the burden easily.”

Likewise, loving-kindness should be recited and developed in respect of the remaining nine directions. For now, it would be sufficient to recite and develop the first and the last phrase. Let’s do the recitation.

2. May all beings in the West be free from enmity,” “May they be free from mental distress or suffering,” “May they be free from bodily suffering or injury,” “May they keep themselves happy and carry the burden easily.”

“May all beings of the lower realms in the West be free from enmity,” “May they be free from mental distress or suffering,” “May they be free from bodily suffering or injury,” “May they keep themselves happy and carry the burden easily.”

3. “May all beings in the North …

4. “May all beings in the South …

5. May all beings in the South-east …

6. May all beings in the North-west …

7. May all beings in the North-east …

8. May all beings in the South-west …

9. May all beings in the Nadir …

10. May all beings in the Zenith …

What has now been recited is a brief, but comprehensive, account of the 528 kinds of loving-kindness. This how those who are accomplished in meditation on loving-kindness immerse themselves in absorption. Those who have not yet achieved absorption, could also radiate loving-kindness in the same way. Those who have special perfections may attain absorption. Even if they fail to attain absorption, benefits will undoubtedly accrue as mentioned below.

“Monks! A monk, by practising loving-kindness (for the sake of another’s happiness), even for a moment,¹¹ (and if borne in mind attentively), the monk who has thus developed loving-kindness is called ‘One not devoid of concentration.’ He conforms to the Teacher’s instruction, and does not eat the country’s almsfood in vain. What, then, could be said regarding those monks who have frequently practised and developed the thought of loving-kindness? This is the teaching of the Buddha, so there is no doubt that developing loving-kindness is highly beneficial.

According to this teaching, even if the thought of loving-kindness is fostered for a split-second, he who exercises this goodwill or benevolent feeling towards others may be said to be a person who is not devoid of concentration. He should be regarded as a person who practises in accordance with the instruction of the Blessed One. If he is a monk, he is worthy of enjoying the meals offered by his supporters. He may be regarded as having appreciated the meals offered, enabling the donor to gain merits and benefits. If the meals are taken by the monks without reflection, it would amount to accepting meals by way of borrowing. The reason being that if a monk, not being accomplished with morality, eats the meals that should be consumed only by a monk fully endowed with all four kinds of moral purity,¹² it is like taking meals on credit, saying that he would only later repay it by fulfilling the required morality. Also full benefits will only be derived by the alms-giver if he offers anything in charity to a monk who is fully accomplished with fourfold moral purity. The Commentaries say that partaking of the four requisites — almsfood, robes, medicines, and dwelling — without due reflection, amounts to using things on credit, which he will have to account for later.

A monk who develops loving-kindness towards others even for a moment shall be deemed to have accepted the gifts as a true owner. He is like one who inherits property. That is why it may be construed as partaking of things offered without futility. The Commentary goes on to say “Offerings given to the Saṅgha (saṅghe dinnā dānaṃ) have great reward (mahāthiyaṃ hoti mahapphalaṃ).” For being beneficial it may be said to be consumed without futility.

Loving-kindness Practised by the Elder Subhūti

The exercise of mindfulness on loving-kindness can bring about great benefit for the donors. Since this is so, the elder Subhūti, an Arahant, used to enter into the absorption on loving-kindness while stopping for a while in front of every house when going round for alms. Only after arising from this absorption on loving-kindness, did he accept the offering of food. He did this to bestow beneficial results on the donors. The elder Subhūti later received the highest praise from the Buddha, being declared pre-eminent among all of his disciples as a recipient of alms. Nowadays, when religious functions are held in connection with the offerings of charity, the Metta Paritta is recited by the monks for the benefit of the donors. Hence, whenever chanting the Mettā Paritta as a blessing on such occasions, it should be reverentially recited while practising loving-kindness.

It is important to note that developing loving-kindness while listening to a talk is really advantageous. Loving-kindness needs to be developed as and when an opportunity occurs, wherever you may be. At least it should be developed immediately after worshipping the Buddha, as time permits. If circumstances are favourable, absorption can be achieved quickly when loving-kindness meditation is developed, as in the case of Dhanañjāni, a Brahmin.

Loving-kindness Practised by Dhanañjāni Brahmin

When Dhanañjāni, the Brahmin, was on the threshold of death in his sick-bed, a request was made at his behest to invite the elder Sāriputta. The elder responded to the invitation and came to see Dhanañjāni. The elder asked him how he was getting on, whether he was feeling better or not, and then, taught as follows:

When asked, “Of the two, rebirth in hell or rebirth as an animal, which is better?” Dhanañjāni answered, “Animal rebirth is better.” On being questioned further, regarding animal rebirth or as a hungry ghost, as a hungry ghost or a human, human rebirth or rebirth among the deities of the Four Great Kings (Cātumahārājikā devā), and thus up to the highest heaven of the deities who delight in the creation of others (Paranimmitavasavattī devā), Dhanañjāni replied each time that the latter was best. Then the elder asked which was better, the life of a deva or that in the Brahma realm. On hearing ‘Brahma realm,’ Dhanañjāni became encouraged and asked with an exultant feeling, “Did you, my dear Venerable Sāriputta, really mean to say ‘Brahma realm’?” This question made the elder realise that Dhanañjāni was mentally inclined towards rebirth in the Brahma realm, so he said that he would explain the practice leading to the Brahma realm. Then he started teaching as follows:

“Idha, Dhanañjāni, bhikkhu mettāsahagatena cetasā ekaṃ disaṃ pharitvā viharati, tathā dutiyaṃ, tathā tatiyaṃ, tathā catutthaṃ; iti uddhamadho tiriyaṃ sabbadhi sabbattatāya sabbāvantaṃ lokaṃ mettāsahagatena cetasā vipulena mahaggatena appamāṇena averena abyābajjhena pharitvā viharati. Ayaṃ kho, dhanañjāni, brahmānaṃ sahabyatāya maggo.”¹³

Dhanañjāni: Dhanañjāni Brahmin, Idha bhikkhu: a monk in this noble dispensation, mettāsahagatena cetasā: with a mind of loving-kindness wishing others to be happy, ekaṃ disaṃ: towards all beings living in one region or direction, pharitvā viharati: abides radiating loving-kindness, tathā dutiyaṃ: likewise he remains radiating loving-kindness to a second direction, tathā tatiyaṃ … tathā catutthaṃ: and in the same way he radiates loving-kindness to the third and fourth directions; iti: thus, uddham: to all beings in the higher realms, adho: to all beings in the lower realms, tiriyaṃ: to all beings in the four directions, sabbadhi: everywhere, sabbattatāya: regarding all beings equally with loving-thoughts, sabbāvantaṃ lokaṃ: to all other beings in the entire universe, mettā sahagatena cetasā: develops the mind wishing happiness to others, vipulena: and spreading the mind to cover all areas. Mahaggatena: with a lofty mind, appamāṇena: which is boundless, averena: free from hatred, abyābajjhena: free from thoughts of oppression, pharitvā viharati: radiates loving-kindness, Dhanañjāni: Dhanañjāni Brahmin, ayaṃ: the practice of diffusing or radiating loving-kindness, brahmanaṃ sahabyatāya: is for the purpose of staying in the company of Brahmas, maggo: it is the path leading one to become a Brahma.

The gist of it is that radiating loving-kindness to all beings in the ten directions is the path of practice to ascend to the Brahma realm. The way of radiating compassion (karuṇā), rejoicing in others’ happiness (muditā), and abiding in equanimity (upekkhā), has been taught in the same way. After benevolently teaching thus, the Venerable Sāriputta returned to the Jetavana monastery. There, he respectfully related to the Buddha the teachings he had given to Dhanañjāni. Thereupon, the Blessed One reprimanded Venerable Sāriputta thus: “Why did you instruct Dhanañjāni on the path to the Brahma realm, which is inferior when compared to nibbāna, and then get up from your seat and leave?”

The Buddha went on to say that Dhanañjāni had passed away, and had been reborn in the Brahma realm. The Commentary adds that having received this admonition from the Buddha, Venerable Sāriputta visited the Brahma realm and delivered a sermon on the Four Noble Truths to Dhanañjāni Brahmā, and, from that time onwards, whenever any teaching was given relating even to a single verse of four lines, it was always done without omitting the Four Noble Truths.

In this connection what is really intended to be known is that Dhanañjāni, the Brahmin, had been asked to develop loving-kindness, etc., and had thereby attained absorption within a short time of about half an hour before his death. By virtue of this absorption, he reached the Brahma realm. It should therefore be remembered that in the absence of any other special merits on which one can rely at the verge of death, the development of loving-kindness will prove to be a dependable asset. The best thing, of course, is to contemplate, note, and become aware of all phenomena like those who practise and benefit from the method of mindfulness meditation.

Furthermore, the highly beneficial effect of developing loving-kindness was taught by the Buddha in the Okkhā Sutta ¹⁴ of the Nidāna Saṃyutta as described below:

Developing your mind with loving-kindness for a brief period of time involved in milking a cow once in the morning, once in daytime and once at night time, or smelling a fragrance for once only, is far more advantageous than the offering of meals by cooking a hundred big pots of rice, once in the morning, once in the daytime and once at night time, which would, of course, be tantamount to feeding about (3,000) people in all.

It is therefore evident that developing loving-kindness even for a moment is really precious, and one benefits without incurring expenses, spending time, and exerting great labour. Moreover, the advantages of meditation on loving-kindness were taught in the Metta Sutta of the Graduated Discourses, in the Book of Elevens, as follows:

“Mettāya, bhikkhave, cetovimuttiyā āsevitāya bhāvitāya bahulīkatāya yānīkatāya vatthukatāya anuṭṭhitāya paricitāya susamāraddhāya ekādasānisaṃsā pāṭikaṅkhā. Katame ekādasa? Sukhaṃ supati, sukhaṃ paṭibujjhati, na pāpakaṃ supinaṃ passati, manussānaṃ piyo hoti, amanussānaṃ piyo hoti, devatā rakkhanti, nāssa aggi vā visaṃ vā satthaṃ vā kamati, tuvaṭaṃ cittaṃ samādhiyati, mukhavaṇṇo vippasīdati, asammūḷho kālaṃ karoti, uttari appaṭivijjhanto brahmalokūpago hoti. Mettāya, bhikkhave, cetovimuttiyā āsevitāya bhāvitāya bahulīkatāya yānīkatāya vatthukatāya anuṭṭhitāya paricitāya susamāraddhāya ime ekādasānisaṃsā pāṭikaṅkhā”ti.

Eleven Advantages of Loving-kindness

Eleven Advantages of Loving-kindness

In brief, the eleven advantages of loving-kindness, which are worthy of note and bearing in mind, are the mental states that have been developed, practised, and frequently relied upon, like vehicles that have been maintained properly and kept ready for use. They are those mental states that have been properly practised and firmly established. The thoughts of loving-kindness should be free from hindrances such as ill- will. Ordinarily, loving-kindness is regarded as merely the mind of good-will. However, when speaking of serenity emancipated from human passions (cetovimutti), it should be regarded as mettā-jhāna. It has been explained as such in the Commentary.

The eleven advantages of loving-kindness are:

Sukhaṃ supati: he sleeps happily.¹⁵ (1) Those who lack practice in meditation are restless before falling asleep; they may perhaps snore. On the other hand, a person accustomed to meditation on loving-kindness has a peaceful sleep with an undisturbed mind. Once fallen asleep, he or she sleeps happily just like a person in absorption. This is the first advantage.

Sukhaṃ patibujjhati: he awakes happily. (2) When waking up from sleep some get up with a grumble. Some have to stretch their arms and legs, roll over, or make other movements before getting up from bed. Those who go to sleep after developing loving-kindness will not suffer such discomfort. They awake from sleep happily and as fresh as flowers in full bloom. According to the Dhammapada verses: “Those who recollect the noble attributes of the Buddha, sleep soundly and wake happily.” It should be noted that special emphasis has purposely been made on the peculiar characteristics of meditation on loving-kindness because of its qualities in deriving such benefits.¹⁶

Na pāpakaṃ supinam passati: he dreams no evil dreams. (3) Some have nightmares such as falling down from a high altitude, being mistreated by others, or being bitten by a snake. A person who develops loving-kindness will not have such frightening dreams, but will have pleasant dreams, as if worshipping the Buddha, flying through the air with psychic powers, listening to sermons, and such things that give delight.

Manussānaṃ piyo hoti: he is pleasing to human beings. (4) Others will adore the meditator because of his or her noble attributes. The meditator radiates loving-kindness to others and will never harm anyone. Relatives and friends will not find fault, and since a meditator is tolerant, having serenity and compassion for others, he or she is loved and respected by all. Sincere loving-kindness is a noble attribute that invokes the affection and respect of others.

Amanussānaṃ piyo hoti: he is also loved by non-human beings. (5) The fourth and the fifth advantages show that he is loved by all human and celestial beings. An instance is related in the Visuddhimagga to show how love and respect are bestowed by celestial beings.

The Story of Visākha

At one time, a rich man by the name of Visākha lived in the city of Pāṭaliputta. While residing in Pāṭaliputta, he heard travellers tales regarding the existence of Buddhist shrines and pagodas in the island of Sri Lanka so numerous that they resembled a necklace of flowers. The entire place was said to be glowing with the bright colour of yellow robes worn by the Saṅgha. Every place was safe and secure and one could reside peacefully, spending the night anywhere without fear. The weather was moderate and conducive to good health. The serenity of the monasteries was matched by the refined and gentle behaviour of the people, both in thought and deed, creating a congenial atmosphere for listening to the Dhamma talks with peace of mind and devotion.

These idyllic impressions aroused in him the wish to go to Sri Lanka and enter the Saṅgha. With this intent, he transferred all of his property and business assets to his wife and children, and having done so, left home with only one rupee in his pocket. He had to wait for a month at a seaport before he could set off by an ocean-going vessel. In those days, ocean-going vessels were not steamships, but large sailing boats. Since he had a natural gift for doing business, he started trading, buying and selling goods here and there while waiting for the boat to arrive. Within a month, he had earned a thousand rupees by honest trading. Trading in an honest way means buying goods for their true value and selling them on at a fair profit. In ancient times, a profit margin of only two two percent was usually taken. Trading goods by fair means with the correct price means legal and honest trading (vammika vaṇijjā). Trading in a legitimate way for one’s livelihood is right-livelihood (sammā-ājīva). However, it seems that Visākha’s intention was not to trade for a profit motive, but was just his natural inclination.

This is evident from the fact that he had later discarded all his money derived from his business venture. Visākha left the port and reached Sri Lanka, where at the Mahāvihāra, he requested to be ordained as a monk. On his way to the ordination hall (sīma), one thousand rupees that he carried in a pouch tucked up at his waist, slipped out accidentally. When the senior monk who was escorting him to the ordination hall asked him what this money was for, he replied, “Venerable sir, this is my own money.” On being told by the senior monks, “Lay disciple, according to the monastic rules, from the time of your ordination, you cannot handle or make use of money. You should dispense with this money right away.” Visākha replied, “I do not wish to see those who favour me with their presence at my ordination return home empty-handed.” So saying, he threw away the thousand rupees, letting them fall among the crowd of devotees outside the precincts of the ordination hall. Having done so, he received ordination.

The rich man was named as Venerable Visākha. For five years, he studied hard, and undertook training in the disciplinary rules and precepts called “Dvemātikā.” After the completion of five rainy seasons, he took up meditation practice for four months at each of four different monasteries. While practising thus, he once made his way to a forest retreat, and there made a joyous utterance, reflecting on his noble attributes, as follows:

“Yāvatā upasampanno, yāvatā idha āgato.

Etthantare khalitaṃ natthi, aho lābhā te mārisa.”¹⁷

Yāvatā upasampanno: from the time of my ordination, yāvatā idha āgato: until I arrived at this forest retreat, etthantare: during this period, khalitaṃ: failure in the observance of moral precepts, natthi: had never happened, mārisa: O, Venerable Visākha, te: your, lābhā: gains and benefits relating to morality, aho: are wonderful!

Later, Venerable Visākha proceeded to a monastery on Cittala mountain situated at the extreme end of the southern range. On his way, he reached a junction in the road where he stopped for a while, undecided as to which route he should take. At this point, a guardian angel of the mountain appeared and directed him towards the right path saying, “This is the route that you should take.” After four months had elapsed since his arrival at Cittala monastery, on one day at dawn he was lying down, planning to leave the monastery for another place. While he was thus reflecting, the guardian deity of a maṇila tree, which stood at the head of the walking path, sat on the stairs, crying. The elder Visākha asked, “Who are you and why are you weeping?” The guardian deity replied, “I am the guardian deity of that maṇila tree.”

When asked why he was weeping, the deity replied that he felt sad and dejected due to the imminent departure of the elder. Visākha then asked again, “What advantages have you derived from my stay here?” The guardian deity replied, “Venerable sir, your presence here has brought about a loving-kindness among the deities; and if you leave this place, quarrels will break out among the deities who will utter harsh speech hurting one another’s feelings.” Visākha then said, “If my stay here will bring happiness to you all, I will have to stay on.” He continued to reside at the monastery for another four months.¹⁸ Similar incidents happened again at the end of every four months, and the elder Visākha therefore had to remain at the Cittala monastery until the time of his parinibbāna. This anecdote in the Visuddhimagga is a clear example showing how a person who develops loving-kindness is loved and respected by celestial beings.

Devatā rakkhanti: the deities protect him. (6) The manner of giving protection is said to be similar to the kind of protection given by parents to their only son through love. If the deities are going to render help and protection, one will definitely be free from dangers, and will gain happiness.

Nāssa aggi vā visaṃ vā satthaṃ vā kamati: neither fire, nor poison, nor swords can harm him. (7) When a person is developing loving-kindness, neither fire, nor poison, nor swords (or any other dangerous weapon) can cause physical harm. In other words, no weapon can injure an individual who is developing loving-kindness. Firearms, bombs, missiles and such other modern weaponry that can inflict harm on a person may be regarded as included in the list of lethal weapons.

Therefore, when any kind of danger is imminent, it is advisable to seriously develop meditation on loving-kindness. The Visuddhimagga cites a number of instances, such as that of the female devotee Uttarā who escaped scalds from boiling oil, or that of Cūḷasiva Thera, a famous scholar of the Saṃyuttanikāya who was immune from poison, or the case of Saṃkicca Sāmaṇera who had escaped from the deadly effects of sharp weapons. A story of a cow that was invulnerable to the blows of a spear was also cited. At one time, a cow was feeding an infant calf. A hunter tried to hit this cow several times with his spear. However, every time the sharp-pointed spear-head struck the body of the cow, the pointed edge of the spear twisted or coiled up like a palm leaf instead of penetrating through the skin. This happened not because of access concentration or absorption, but because of her pure and intense love for her young calf. The influence of loving-kindness is indeed that powerful. Among these stories, the one relating to Uttarā found in the Dhammapada Commentary is outstanding. This is a brief account:

The Story of Uttarā

Uttarā’s father was a poor man named Puṇṇa, an employee of Sumana, a millionaire in the city of Rājagaha. One day, he donated a thin stick of a vine, a kind of tooth-brush used by monks for cleaning the teeth, and clean water for washing the face, to the elder Sāriputta who had just arisen from the attainment of cessation. On the same day, his wife, on her way to the place where he was ploughing the field bringing a packet of rice for him, met the elder. With overwhelming joy at the sight of the elder, she offered the rice to the Arahant and shared her merits with her husband. By virtue of these meritorious deeds, it is said that the entire plot of land ploughed by Puṇṇa suddenly transformed into a field of pure gold. At the present day, this kind of incident may be considered ludicrous — a mere fairy tale. However, in those ancient times, special and extraordinary benefits were derived due to the outstanding moral virtues of certain recipients or donors who possessed special noble attributes. There is reason to believe these stories, considering the remarkable inventions of electronic and mechanical devices such as computers, missiles, and satellites which would ordinarily be considered unbelievable. Peculiar and astonishing events might, therefore, have occurred in those days.

Since his plot of cultivable land had turned into solid gold, the poor man Puṇṇa became fabulously rich. Therefore, the wealthy Sumana proposed that Puṇṇa give his daughter Uttarā in marriage to his own son. Puṇṇa, his wife, and Uttarā became Stream-winners after listening to a sermon delivered by the Buddha at the time of the opening ceremony of their new mansion held soon after Puṇṇa had acquired his immense fortune. However, Sumana’s family were of a different religion, and none of the members of their household were Buddhists. For this reason, the proposal made by Sumana was not accepted by Puṇṇa, the millionaire. He told Sumana directly that Sumana’s son had faith in heretical teachers whereas his daughter, being a devout Buddhist, could not help but take refuge in the Triple Gem so the proposed marriage would be incompatible. For this reason he was unable to give his consent to the proposal made by Sumana. However, on being advised by many of his friends not to quarrel with Sumana, he finally acquiesced, and Uttarā was eventually given in marriage to Sumana’s son.

On the full-moon day of July, Uttarā had to accompany her husband to Sumana’s house. Since the day of her arrival at her husband’s house, she had had no opportunity to take refuge, and pay homage to the monks or nuns. Nor did she get any chance to do any act of charity, or listen to the Dhamma. After two and a half months, Uttarā sent a message to her father about her plight. What she had conveyed in her message was: “Why should I be locked up and kept under detention? It would be better to declare me outright that I am their slave. It is unjustifiable to let me be tied down and married to a heretic. Since my arrival here, I have been deprived of the opportunity to see or pay homage to the Saṅgha or perform any meritorious deeds.”

Hearing this news, her father felt very sad, and thought, “My daughter is undoubtedly suffering greatly.” He therefore sent fifteen thousand rupees to his daughter. At that time, a well known prostitute by the name of Sirimā lived in Rājagaha. She earned one thousand rupees a night. Uttarā hired the services of Sirimā for fifteen thousand rupees to look after her husband for fifteen days, using the money sent by her father, to enable her to perform merits during that period. Uttarā’s husband readily gave his permission for Uttarā to devote herself to performing merits for fifteen days, being delighted by Sirimā’s beauty and charm.

Beginning from that day, Uttarā invited the Saṅgha headed by the Buddha daily, and offered alms at her residence. She listened to his talks on the Dhamma, and personally managed the preparation of meals and so forth for the Saṅgha. On the fourteenth waxing day of the full-moon, when looking down at the kitchen from the window of his mansion, her husband saw Uttarā personally managing and supervising the work of cooking food and preparing meals for the Saṅgha. She was perspiring and looking dirty with soot on her face. Seeing her, he mused, “What a fool! She cannot find enjoyment in the luxury of this mansion. How extraordinary that she could only find satisfaction in serving these bald-headed monks!” He then retreated from the window smiling. When Sirimā saw him smile, her curiosity was piqued. Wishing to know the reason for his delight, she went to the window and saw Uttarā in the kitchen. Jealousy rose up in her and she thought, “This millionaire’s son still seems to have affection for this serving woman.” How remarkable, that she considered herself as the lady and owner of the big mansion after only fifteen days. She was oblivious of the fact that she was living there on hire. Thus she became envious and resentful towards Uttarā.

Wishing to hurt Uttarā, she went down the stairs, made her way to the kitchen, took a ladle full of boiling ghee and approached Uttarā to do her harm. Seeing Sirimā, Uttarā immediately reflected and began developing a feeling of loving-kindness, thinking, “My friend Sirimā has been of great benefit to me. The universe is narrow compared to the immeasurable benefits bestowed upon me by Sirimā. The benefits are immense, and it is due to her care and attention given to my husband that I have been able to perform charitable deeds and listen to the Dhamma. If I harbour any feeling of resentment or anger, may this scolding hot ghee that Sirimā is carrying cause me harm. If I have no animosity towards her, may no harm or injury befall me.” Thus she solemnly took an oath regarding her noble-mindedness, and radiated loving-kindness to Sirimā. The hot ghee that Sirimā cruelly poured upon her felt just like cold water. Sirimā then reflected. “This ghee appears to have become cold.” She fetched another ladle of boiling hot ghee from the frying pan. Seeing her doing this evil deed, the maids helping Uttarā became indignant and shouted, “Begone, you ungrateful wretch. Don’t pour burning ghee on our mistress.” They abused her, gave her a good beating, and kicked her, so that she fell to the ground, and Uttarā was unable to stop them. Then Uttarā asked Sirimā, “What made you commit such an evil deed.” So saying, she bathed her with warm water and anointed her bruises with soft cream to relieve her pain.

Only then, Sirimā realised that she was rendering her services on hire. She begged Uttarā to forgive her. Uttarā told Sirimā to ask for forgiveness from her spiritual father, the Buddha. As arranged by Uttarā, Sirimā went to the Buddha, paid homage, offered alms, and asked for forgiveness. Buddha then gave an exhortation, teaching the Dhamma in the form of a verse which, in essence, conveys the meaning, “Conquer anger by patience without spite or retaliation.” After hearing this teaching, Sirimā and five hundred other women attained Stream-winning. The significant point in the story is that Uttarā, the female devotee, escaped from the scalding heat of the boiling ghee poured over her by virtue of developing loving-kindness.

Regarding the story of the elder Cūḷasiva who became invulnerable to poison, no elaborate account was found in the Commentaries or Subcommentaries. The events concerning the novice Saṃkicca, have already been mentioned in my Discourse on the Tuvaṭaka Sutta, where reference is made only to the fact that he had immersed himself in absorption. It was not obvious as to what kind of absorption he had developed. However, according to what is stated in Visuddhimagga, it is to be regarded as developing absorption on loving-kindness. This would mean that immunity was gained from the dangers of fire, poison, and other lethal weapons, such as a sword or a machete.

Tuvaṭaṃ cittaṃ samādhiyati: means that the mind quickly becomes stabilized and calm. (8) To develop mindfulness wishing others to be happy is appropriate and easy in as much as everybody wishes to be happy, so the mind is likely to become tranquil within a short time.

Mukhavaṇṇo vippasīdati: his face is serene. (9) Again, it should be developed as it is appropriate and easy. This will undoubtedly bring a clear complexion to the face.

10) Asammūḷho kālaṃ karoti: he dies unconfused. That is death takes place without bewilderment or perplexity. This is really important. When one is approaching death, one is likely to die without being able to gain proper concentration or mindfulness due to very severe pain or dullness that one has to endure. One is likely to pass away with thoughts of greed, anger, or delusion imagining all kinds of erroneous thoughts. This is how death usually comes upon a person with the mind perplexed and burdened with all kinds of attachments. When death occurs in this way, it is almost certain that one is destined for one of the four lower realms. However, when one is in a semi-consciousness state, if the mind can latch on to thoughts relating to meritorious deeds, or onto signs regarding fortunate destinies such as the abode of celestial beings or the human world, a person can hope to reach an existence where happy conditions prevail.

11) Uttari appaṭivijjhanto brahmalokūpago hoti: if he attains nothing higher he is reborn in the Brahma realm. This is the eleventh advantage, which says that if Arahantship is not realised, which is superior to absorption on loving kindness, he will be reborn in the Brahma realm. An ordinary worldling can reach the Brahma realm if he or she has achieved absorption on loving-kindness. Stream-winners and Once-returners may also be reborn in the Brahma realm. Of course, a Non-returner is likely to be reborn in the Pure Abodes (Suddhāvāsa) in the Brahma realms. If absorption is not attained and if only access concentration is achieved, one can reach the world of human beings and celestial realms, which are fortunate realms of existence. Brahmin Dhanañjāni, whose story was related earlier, reached the Brahma realm by developing loving-kindness, within about half-an-hour prior to his death. This is particularly noteworthy, and worthy of emulation.

Having given fairly comprehensive teachings relating to the Sublime Abidings, I will now say something about insight meditation.

Developing Loving-kindness With Insight

Developing Loving-kindness With Insight

After achieving absorption by developing meditation on loving-kindness a person can reach Arahantship if he or she continues to develop insight with that absorption as a basis. Even if falling short of Arahantship, he or she can become a Non-returner. The way to contemplate is to first enter into absorption on loving-kindness, and when this absorption ceases, to contemplate that absorption. This method of plunging into absorption, then contemplating it by alternately developing tranquillity and insight in pairs is called “yuganaddha.” The method of developing insight is the same as the method of noting and contemplating used by the meditators here. It is to contemplate and note what has been seen, heard, touched, or imagined as “seeing,” “hearing,” “touching,” or “imagining,” as appropriate. Likewise, after leaving absorption, this absorption should be noted and contemplated. The only difference is that a person who has attained absorption, contemplates the absorption, whereas other meditators, not being endowed with absorption, should note and contemplate the mind or consciousness that is aware of what was seen, and so forth.

What should be done according to this method of contemplation in pairs is to develop loving-kindness by repeating: “May all beings be happy.” Then, contemplate with the thoughts of loving-kindness. Developing loving-kindness along with the contemplation of the thoughts in pairs is the “yuganaddha” method. If one contemplates like this, the mind that is radiating loving-kindness to a particular person while reciting, the material element of the sound, the ear-consciousness that hears, and the mind-consciousness that dwells in the heart while reciting: “May all be happy,” will all be found to vanish instantaneously and repeatedly. Such realisation is genuine insight knowledge that knows the characteristic of impermanence. This is stated as having vanished instantly (khayaṭṭhena aniccaṃ), so it is impermanent. Let us bear it in mind and contemplate while reciting like this:

“May all the monks, meditators, and individuals residing in this meditation centre be happy.”

“May all beings in this meditation centre be happy.”

“May all monks and individuals within this town be happy.”

“May all beings in this town be happy.”

“May all people living in this country be happy.”

“May all beings be happy.” (Repeat thrice)

Every time it is recited as: “May all be happy” with consciousness, the mind that is put into this consciousness, and the mind that intends to recite, the vocal action, and the sense object of the voice that utters, immediately vanish.

Part Two

Part Two

On the full-moon day of July, I taught how to develop loving-kindness. Most of the teachings given then, referred to the cultivation of perfections and wholesome kamma by developing loving-kindness. From the method as explained in the Visuddhimagga, we have so far only covered the way of reflecting the faults of anger, and the benefits of patience. I will now continue to teach how to develop loving-kindness.

Way of Sitting Comfortably

I will add a little more according to the teachings of the Buddha relating to assuming a comfortable sitting posture. The Blessed One advised going into or residing in a forest (araññagato vā), or sitting at the foot of a tree (rukkhamūlagato vā), or staying in an empty building (suññāgāragato vā), and that one should sit down (nisīdati). Obviously the Buddha gave priority to practising meditation in a forest. If one is unable to go to a forest, he advised meditating at the foot of a tree in a quiet place. If that is not convenient, then one should practise meditation in a monastery, house, or other empty building. It would be best to select a secluded place where there is solitude and tranquillity. If any others are meditating in the same place, it would be best if they are of the same sex. Ideally, the best place would be a secluded spot in a remote area where there is no other person. The sitting posture to be adopted is stated as cross-legged (pallaṅkaṃ ābhujitvā). I have already explained about this in full. Furthermore, the instruction is given that the upper portion of the body above the waist should be kept erect (ujuṃ kāyaṃ paṇidhāya). If one sits bending the back or twisting the spine, one’s effort will be weakened. That is why it is necessary to sit erect keeping the body above the waist perfectly upright. After taking a sitting posture as described, the practice to be followed is to establish attention only on the sense objects as they arise in the present moment (parimukhaṃ satiṃ upaṭṭhapetvā) and to engage in active meditation without letting the mind wander. In the case of meditation on loving-kindness, the mind should be directed towards people for whom loving-kindness is to be developed. It is essential to know who are those to whom loving-kindness should not be radiated at first, and who are not suitable.

Unsuitable Persons

At the beginning of the practice, loving-kindness should not be developed towards: 1) those who are hostile, unfriendly, or disliked; 2) those who are dear to you, that is, those for whom you hold a deep affection; 3) those for whom you feel indifference; and 4) those who are enemies.

Not developing loving-kindness for such people when beginning meditation is justified because it would be difficult to send loving-kindness to one whom you hate. It is also unwise to send loving-kindness to your children, brothers, and sisters for whom you have a strong affection and attachment. Neither will it be easy to develop loving-kindness for people such as your own pupils or disciples, because if persons for whom you have deep love and affection are found to be unhappy or suffering trouble and misery, you would probably become anxious or dejected. Again, it may be difficult to put a complete stranger or a neutral person in the role of a beloved person. It is nearly impossible to radiate constant loving-kindness to a complete stranger, let alone to an enemy. The moment you remember an enemy, feelings of anger will arise when you recall his or her evil deeds or faults. These are the four kinds of people for whom one should not develop loving-kindness at the initial stage of meditation.

Furthermore, loving-kindness should not be developed at all towards:

1) Persons of the opposite sex. Loving-kindness should not be developed and radiated to persons of the opposite sex.

2) Loving-kindness should not be developed towards the dead.