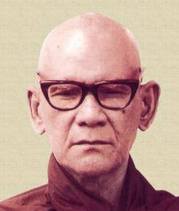

Mahāsi Sayādaw

Mahāsi Sayādaw

Dhamma Therapy Revisited

By the Venerable Mahāsi Sayādaw

Download the » PDF file (764 K) to print your own booklets.

Contents

How the Buddha Was Cured of Illness

Two Cases Related by Mahāsi Sayādaw

Seven Cases Narrated by Sayādaw U Sujāta

Some Remarkable Cases: Sayādaw U Paṇḍita

Special Cases of Cures: Sayādaw U Saṃvara

Healing as a Result of the Enlightenment Factors

Editor’s Foreword

HIS book started life as a talk to students at Rangoon University in 1974, published in Burmese as the book “A Special Discourse on Vipassanā.” Ven Aggacitta Bhikkhu translated the appendix to it compiled by Ven Mahāsi Sayādaw and this was published as “Dhamma Therapy,” in 1984 by the Malaysian Buddhist Meditation Centre. Ven Aggacitta Bhikkhu updated this work and it was published by the Sāsanārakkha Buddhist Sanctuary in 2009.

HIS book started life as a talk to students at Rangoon University in 1974, published in Burmese as the book “A Special Discourse on Vipassanā.” Ven Aggacitta Bhikkhu translated the appendix to it compiled by Ven Mahāsi Sayādaw and this was published as “Dhamma Therapy,” in 1984 by the Malaysian Buddhist Meditation Centre. Ven Aggacitta Bhikkhu updated this work and it was published by the Sāsanārakkha Buddhist Sanctuary in 2009.

With the permission of Ven Aggacitta, I have reformatted and edited this 2009 edition for the Association for Insight Meditation. I have made some minor changes to replace some Pāli terms with their English translations to make the work easier to read for those less familiar with Buddhist terms than Asian Buddhists would be.

I first met Aggacitta in 1979 at the Mahāsi Yeikthā where he obtained the Higher Ordination with the Mahāsi Sayādaw as his preceptor in December of that year. He was also the translator of the talks given by Sayādaw U Paṇḍita at Barre Mass, which were later published in book form as In This Very Life.

Bhikkhu Pesala

September 2021

Dhamma Therapy Revisited

Dhamma Therapy Revisited

by

Venerable Mahāsi Sayādaw

Translated by Aggacitta Bhikkhu

Preface

N the early ’80s I started to translate the appendix compiled by Ven Mahāsi Sayādaw in the book version of “A Special Discourse on Vipassanā,” a talk he delivered to Rangoon ¹ University students in 1974. Sandwiched between his scholarly introduction and conclusion lies the appetising main portion of the work dealing with the miraculous healing of sicknesses in the course of intensive vipassanā meditation.

N the early ’80s I started to translate the appendix compiled by Ven Mahāsi Sayādaw in the book version of “A Special Discourse on Vipassanā,” a talk he delivered to Rangoon ¹ University students in 1974. Sandwiched between his scholarly introduction and conclusion lies the appetising main portion of the work dealing with the miraculous healing of sicknesses in the course of intensive vipassanā meditation.

These cases were either related personally by the yogis or recorded by highly competent meditation teachers. In the process of finalising the translation, I coined the term ‘Dhamma therapy’ as vipassanā meditation is the heart of Dhamma, the teaching of the Buddha. While the aptness of ‘Dhamma therapy’ seems to be self-evident because the subject matter deals with healing through vipassanā meditation, it is even more obvious when you realise that ‘Dhamma-striving’ and ‘Dhamma-sitting’ are popular Burmese expressions for meditation.

It is indeed a most humbling experience to look anew at a published translation done more than 25 years ago when my knowledge of Pāḷi was still rudimentary. Neither the fact that the work was published without my vetting the proofs (I had just begun my private quest for forest seclusion) nor that I had merely translated Ven Mahāsi Sayādaw’s Burmese translation of the Pāḷi passages is valid justification for the glaring deficiencies that I now perceive in it. In this revised edition, I have tried to make amends to the best of my current ability.

One of my original motivations for undertaking the translation of this somewhat obscure appendix was to provide inspiration for English-speaking newcomers to the practice of vipassanā. Many of them, unlike their more fortunate Burmese counterparts, would probably not have the opportunity to do long-term intensive retreats under the daily scrutiny and guidance of skilful teachers ever ready to give inspiration and persistent encouragement. They must therefore be content with having to fight the often losing battle against painful, boring, restless, or sleepy sitting sessions.

However, after completing the first draft of the translation, it occurred to me that old-timers may also be inspired by many of the accounts which remind us of the unfailing power of courage, persistence, endurance and patience. Such accounts may even whet the appetite of more adventurous general readers who may not be so interested in liberation and enlightenment. Being inspired by the miraculous success stories, they may be drawn to a more profound appreciation of the wonderful Dhamma by personally experimenting with vipassanā practice—even though they may be initially motivated by a purely mundane wish to be rid of some chronic ailment. Any initial success may spur them to become more committed to the practice and eventually upgrade their motivation to a loftier one.

The hardcore Theravādin stickler for evidence from canonical, commentarial and sub-commentarial sources to support the claims of contemporary yogis will find a welcome challenge in Ven Mahāsi Sayādaw’s authoritative introduction and conclusion to the main exposition.

Aggacitta Bhikkhu

July 2009

Acknowledgement

Acknowledgement

ANY people contributed to the publication of the translation in the early ’80s. Sayādaw U Paṇḍitābhivaṃsa, then Ovādācariya Sayādaw of Mahāsi Meditation Centre, Rangoon, Burma, clarified some of the more difficult Burmese translations of Pāḷi terms in his typically precise and succinct way. The late Dr U Ba Glay, then Vice-President of the Buddhasāsanānuggaha Organisation (which manages the Mahāsi Meditation Centre in Rangoon/Yangon), gave encouragement and supplied English equivalents for some Burmese medical terms and English spellings of Burmese proper nouns. When I was briefly back in Malaysia (April – June 1982) editing the second draft translation, a couple of Burmese medical expatriates then attached to the Tanjung Rambutan Psychiatric Hospital helped to check, confirm or supply alternatives for some of the more abstruse English translations of symptoms and illnesses found in the Burmese original. The inquiries were made through Lim Koon Leng, a staff member of the hospital who was also a lay supporter and member of the meditation society in which premises I was then residing.

ANY people contributed to the publication of the translation in the early ’80s. Sayādaw U Paṇḍitābhivaṃsa, then Ovādācariya Sayādaw of Mahāsi Meditation Centre, Rangoon, Burma, clarified some of the more difficult Burmese translations of Pāḷi terms in his typically precise and succinct way. The late Dr U Ba Glay, then Vice-President of the Buddhasāsanānuggaha Organisation (which manages the Mahāsi Meditation Centre in Rangoon/Yangon), gave encouragement and supplied English equivalents for some Burmese medical terms and English spellings of Burmese proper nouns. When I was briefly back in Malaysia (April – June 1982) editing the second draft translation, a couple of Burmese medical expatriates then attached to the Tanjung Rambutan Psychiatric Hospital helped to check, confirm or supply alternatives for some of the more abstruse English translations of symptoms and illnesses found in the Burmese original. The inquiries were made through Lim Koon Leng, a staff member of the hospital who was also a lay supporter and member of the meditation society in which premises I was then residing.

Hoe Soon Ying and Lee Saw Ean prepared the first typescript at very short notice, while Goh Poay Hoon assiduously made amendments through seemingly endless rounds of revisions. In those pre-PC days, this was quite a feat of patient dedication. Steven Smith of Hawaii who was then Ven U Dhammadhaja took valuable time off from his meditation retreat at Vivekasrom, Chonburi, Thailand (February – March 1983) to read through a late draft and gave some valuable suggestions. Finally, Buddhasāsanānuggaha Organisation approved the translation for publication in 1984.

To all these contributors, I am abundantly grateful.

Notes on the Translation

Notes on the Translation

General

HAVE replaced the word-for-word, Pāḷi to English (nissaya) style of translation employed in the main text of the original edition with a simpler, less literal translation and shifted the accompanying Pāḷi texts to the footnotes. This retains the translator’s freedom of rendering, while enabling the more knowledgeable reader to critically appraise the interpretation. Apart from these Pāḷi texts and unless otherwise stated, I am responsible for the contents of the footnotes.

HAVE replaced the word-for-word, Pāḷi to English (nissaya) style of translation employed in the main text of the original edition with a simpler, less literal translation and shifted the accompanying Pāḷi texts to the footnotes. This retains the translator’s freedom of rendering, while enabling the more knowledgeable reader to critically appraise the interpretation. Apart from these Pāḷi texts and unless otherwise stated, I am responsible for the contents of the footnotes.

Sati and mindfulness

More popular among the English translations of the Pāḷi word sati are ‘mindfulness’ and ‘recollection.’ The Burmese Pāḷi scholars formally render it as ‘recall’ (literally, ‘getting the mark,’ ‘note’). Sati has been assimilated into the Burmese language and combined with other words, giving meanings such as ‘remember,’ ‘remind,’ ‘pay attention,’ ‘be careful,’ ‘beware,’ ‘be aware,’ ‘warn,’ ‘caution,’ and so on. ‘Recall’ may be an accurate and sound translation of the Pāḷi term, but to use this formal rendition in the practice of vipassanā meditation without first clarifying its sense would be confusing.

Hence, Ven Mahāsi Sayādaw does not hesitate to point out that ‘recall’ practically means “the observant noting, by labelling ‘seeing, seeing,’ ‘hearing, hearing,’ etc. at each of their respective occurrence.” It should be noted that the stress on the ‘here and now’ in vipassanā practice refers to the moment of perceptible occurrence of all sensory processes within oneself—including mental activity such as thoughts, imaginings, emotions, etc.—and not to the ‘present’ of the Abhidhamma time-scale of unit-consciousness.

In this work I use ‘mindfulness’ for sati and change it according to the Pāḷi grammatical form, e.g. sato = ‘being mindful’ or ‘mindfully.’ Note that “mindfulness” should also connote the ‘recollective’ mode implicit in the original meaning of ‘recall.’ In practical vipassanā terms, this means ‘looking’ back at an immediate past occurrence, e.g. when you note “thinking, thinking” the moment you realise that a thought has occurred. Obviously when you are noting “thinking, thinking,” the thought is an immediate past object that you are ‘looking’ back at, i.e. remembering, recollecting, or recalling.

Dhamma-striving and meditation

‘Striving for the Dhamma’ and ‘Dhamma-striving’ are variations of ‘to Dhamma-strive,’ a literal rendering of the short but precise Burmese phrase used to express a practice that demands so much exertion, perseverance, and commitment. In the original edition entitled Dhamma Therapy, I experimented with these renderings in place of the English ‘meditation’ and ‘to meditate’ in order to convey their connotations, but I now think that the nuances are not worth preserving at the expense of the word ‘meditation’ which is now widely understood to roughly mean “Engaging in mental activity of a spiritual nature, but not necessarily confined to thinking.” While this is not exactly the meaning of the Burmese terms ‘Dhamma-striving’ or ‘Dhamma-sitting,’ I nevertheless concede to render them as ‘meditation’ for the sake of easy reading.

Guide to non-English words

Any non-English word, other than proper nouns, that occurs only once in the main text is either accompanied by its English translation in round brackets or explained in a footnote. Other non-English words in the main text, including some proper nouns, and a few medical terms are explained in the Glossary.

How the Buddha Was Cured of Illness

How the Buddha Was Cured of Illness

URING his forty-fifth and final Rains Retreat (vassa) the Buddha was residing at Vesāli Township, in the village of Veḷuva. It is recorded in the Mahāvagga of the Dīgha Nikāya (DN 16, LDB p244) and the Mahāvagga of the Saṃyutta Nikāya (SN 47:9, CDB p1636) that the Buddha was then afflicted with a serious and pervasive illness, of which he was eventually healed through Dhamma therapy:

URING his forty-fifth and final Rains Retreat (vassa) the Buddha was residing at Vesāli Township, in the village of Veḷuva. It is recorded in the Mahāvagga of the Dīgha Nikāya (DN 16, LDB p244) and the Mahāvagga of the Saṃyutta Nikāya (SN 47:9, CDB p1636) that the Buddha was then afflicted with a serious and pervasive illness, of which he was eventually healed through Dhamma therapy:

“At that time [in Veḷuva Village] a severe illness arose in the Blessed One who had entered the Rains Retreat (vassa). Deadly, excruciating [physical] feelings occurred. Being mindful and aware, the Blessed One endured them without being distressed [or oppressed].” ²

The above canonical record of how patience was maintained while he was being mindful and aware, and of the apparent non-occurrence of oppression or distress due to pain are further elaborated on in the Commentary:

“Being mindful and aware he endured” means “having made mindfulness such that it manifests clearly [i.e. having properly established mindfulness], having discerned [the nature of feeling] through [insight] knowledge, he endured.” ³

The Subcommentary glosses:

“Having discerned through knowledge” means “having discerned with [insight] knowledge the momentary existence of the [painful] feelings [as they break up into segments], or their suffering nature, or the absence of atta.” “He endured” means “while subduing the pain and by virtue of noting/noticing whichever mannerism [i.e. anicca, dukkha or anatta] thoroughly ‘digested’ [by insight], he accepted and tolerated those feelings within himself. He was not overwhelmed by the pain.” ⁴

The Commentary continues:

“Without being distressed” means “without making repeated or frequent shifting/moving actions in order to alleviate the painful sensation, he endured, [as if] not being oppressed, [as if] not undergoing pain or suffering.” ⁵

The above is an exposition according to the Commentary and Subcommentary. Nowadays when yogis gain an insight into the moment-to-moment occurrence of pain and its segmental breaking up while engaged in mindfully noting “pain, pain,” and so forth, the relief of pain and the painless state of ease and comfort may be experienced. That the foregoing exposition is in conformity with the practical experience of yogis today is quite obvious.

Continuing with the canonical record:

“At that time it occurred thus to the Blessed One: “If I should pass away into parinibbāna ⁶ without having informed my attendant disciples, without having notified the community of monks, this act of mine would indeed not be proper. It would be well if I should dwell, having removed this illness by [diligent] effort and undertaken the repair of vitality.” ⁷

The Commentary points out two types of [diligent] effort—one relating to vipassanā meditation and the other to phalasamāpatti. That the latter is meant by “diligent effort” may not be so clear since phalasamāpatti is due merely to the effect of the Noble Path (ariyamagga) brought forth by the power of vipassanā meditation. Instead it will become quite clear that diligence in vipassanā meditation only is being referred to.

“Then (after thinking thus) the Blessed One dwelled, having removed the illness through (meditative) effort (and) undertaken the repair of vitality. (Thus dwelling) at that time the (deadly and intense) illness of the Blessed One was stilled (i.e. cured).” ⁸

In this connection the Commentary further elaborates on how the illness vanished.

“On that day [probably on the 1st waning night of Waso],⁹ the Blessed One—just as he had induced new[ly discovered] vipassanā meditation on the seat of the great bodhi tree [beneath which he was to attain Buddhahood]—having executed the seven ways of contemplating matter (rūpa) and the seven ways of contemplating mind (nāma) ¹⁰ without obstruction, without entanglement; having conducted to completion the fourteen ways of meditation; having rooted out the pain [of the illness] through great (panoramic) vipassanā,¹¹

At this point it becomes apparent that painful sensations can be removed by vipassanā meditation.

…resolved thus: ‘For ten months [from the 1st waning day of Waso till the full moon day of Kasone] ¹² let these [painful sensations] not occur,’—and attained phalasamāpatti. Rooted out by samāpatti, for ten months [till the morning of the full moon day of Kasone] the [painful] sensations [of the illness] never did arise.” ¹³

In the Pāḷi Canon and Commentary it is clearly shown that painful sensations can be removed by means of vipassanā meditation or phalasamāpatti. It should therefore be noted that Noble Ones (ariya) ¹⁴ may be relieved of painful sensations through two ways, namely vipassanā and the attainment of fruition (phalasamāpatti); while for ordinary worldlings (puthujjana),¹⁵ only by means of vipassanā. The possibility of healing sicknesses and removing painful sensations through the one way of vipassanā can also be credibly noted in the contemporary case accounts related [by leading meditation teachers of the Mahāsi tradition] in the next chapter.

Two Cases Related by Mahāsi Sayādaw

Two Cases Related by Mahāsi Sayādaw

1. Cured of chronic wind illness

ROUND the year 1945 at a village by the name of Leik Chin about four miles north-west of Seik Khun Village, an elder (thera) who had merely heard about Mahāsi Sayādaw’s technique of vipassanā meditation believed in it and practised accordingly in his own monastery. It seems that just a few days later, extraordinary vipassanā concentration and insight knowledge arose and the chronic ‘wind’ illness,¹⁶ which he suffered from for over twenty years, completely vanished. The chronic illness had tormented him ever since he was an eighteen-year-old novice (sāmaṇera) and necessitated daily medicine and massage. Apart from that he was also afflicted by rheumatic aches, which had also required daily massage for relief.

ROUND the year 1945 at a village by the name of Leik Chin about four miles north-west of Seik Khun Village, an elder (thera) who had merely heard about Mahāsi Sayādaw’s technique of vipassanā meditation believed in it and practised accordingly in his own monastery. It seems that just a few days later, extraordinary vipassanā concentration and insight knowledge arose and the chronic ‘wind’ illness,¹⁶ which he suffered from for over twenty years, completely vanished. The chronic illness had tormented him ever since he was an eighteen-year-old novice (sāmaṇera) and necessitated daily medicine and massage. Apart from that he was also afflicted by rheumatic aches, which had also required daily massage for relief.

With the complete disappearance of those ailments while engaged in observant noting, he was thenceforth able to live quite comfortably without having to resort to medicines and massage. It was learnt through his bhikkhu disciples that the elder had deep faith and confidence that any illness whatsoever can vanish if observant noting is done in accordance with the technique of satipaṭṭhāna ¹⁷ meditation. Therefore, whenever he felt unwell or sick he always had recourse to Dhamma therapy without relying on conventional medicine. He would instruct and advise his own bhikkhu disciples, sāmaṇeras, and lay pupils to do the same when they fell sick.

2. Breaking toddy addiction through mindfulness

Seik Khun born Maung Ma lived in Zaung Dan Village, about two miles west of his birth-place. He was young, married, and heavily addicted to toddy. Around the year 1945, his brothers and sisters who had meditated in Mahāsi Monastery persuaded him to do the same. He promised that he would do so and agreed to start on an appointed day. On that day when his brothers and sisters called to get him to start his retreat, they found him intoxicated with toddy. The next day, leaving very much earlier, they arrived before he could take the toddy and successfully escorted him to the meditation hut. Maung Ma meditated seriously according to Mahāsi Sayādaw’s instructions and found so much satisfaction in the Dhamma that he refused to leave the monastery for home. He said he was going to become a bhikkhu.

“Since you have a family, do carry on till you’ve fulfilled your obligations. Next time, when it’s suitable to be a bhikkhu, then do so.” So the meditation Sayādaws cajoled him into going home.

Maung Ma truly revered the Dhamma. It is said that even as he carried goods over his shoulders and peddled his wares, he would maintain unbroken mindfulness; and while reaping paddy too, at each stroke he would try to make at least three mental notes.¹⁸ At one time he wondered whether he still had any longing for toddy. He sniffed a large mug of liquor and then quickly looked into his mind to see if there was any desire to drink it. It seems that while doing so for four, five, or six times vipassanā insight arose and, gathering momentum, culminated in a cessation experience.¹⁹

Later when Maung Ma was undergoing intense suffering due to a fatal illness, he did not lay aside his precious mindfulness. On the night he was to die, he related to his wife, while mindfully noting the sensations in his body: “Oh, now the part of my leg from the ankle to the knee is no longer alive. There is only life till the knee-cap. Oh, now there is life only till the hips…now only to the navel…and now only till the centre of the chest, in the heart.” Stage by stage, he described the changes that took place in his body.²⁰

Finally he uttered, “Soon, I will die. Do not be afraid of dying. One day you too shall have to die. Do make it a point to meditate…” And indeed, soon after those last words to his wife, he died.

This is an account of how Dhamma therapy can free someone from toddy addiction.

Seven Cases Narrated by Sayādaw U Sujāta

Seven Cases Narrated by Sayādaw U Sujāta

1. Woman cured of tumour in the abdomen

N the 3rd waxing day of Tawthalin, 1324 BE [some time in September 1962], Daw Kin Thwe, a woman from Ta Mew, Rangoon, commenced meditation at the city’s Mahāsi Meditation Centre. Three days later I saw a group of yogis massaging her.

N the 3rd waxing day of Tawthalin, 1324 BE [some time in September 1962], Daw Kin Thwe, a woman from Ta Mew, Rangoon, commenced meditation at the city’s Mahāsi Meditation Centre. Three days later I saw a group of yogis massaging her.

“What’s happening?” I asked.

“I’m having gripping pains,” Daw Kin Thwe explained. “There’s a tumour in my belly, so I can’t sit for long. At home too, when friends or visitors come to sit and chat, after only about half an hour or so, my belly aches so badly I have to excuse myself and get a massage to relieve the pain. I visited the doctor for a check-up and he said there was a large tumour in the belly and an operation was necessary to remove it. That was four years ago. This year he said, ‘It won’t do. It must be operated on!’ However, I may die during the operation and I have not yet attained the Dhamma that is a reliable source of refuge. I have to meditate, I thought. With that intention I came here and now after sitting for barely an hour, I get such terrible pains in my belly…”

“And you never even let me know of this at the very start!” I exclaimed. “The Buddha has already expounded in the Mahāsatipaṭṭhāna Sutta (DN 22, LDB p335ff ) that one can be mindful in all the four postures of walking, standing, sitting, or lying. In your case, to prevent the pain from occurring in the belly, you can lean on a wall while you sit, sit on a reclining chair, or even lie down and carry on observant noting. Sit only in such a way that will not be painful. You may sit or lie down, and be mindful as you please. When concentration and insight knowledge arise, your tumour may possibly vanish,” I pointed out to her.

“I will continue to strive according to Sayādaw’s instructions. However, I would still like to visit the doctor for a check-up,” she requested, and I gave her my permission. So she went back home and saw the doctor. It seemed that after examining her the doctor said, “You shall have to undergo an operation to have it removed. You must not continue to meditate. If you do, you might die!”

I came to know that only when she returned, after having spent two days at home.

“In that case you should persist in your meditation. Whether or not you’ll die or the tumour will disintegrate, we shall surely know. If you wish to sit on a chair or sit leaning against the wall and the like, you may do so. While lying down also be mindful. During meal-time too, while gathering food with your fingers, taking and lifting it, opening the mouth, putting it into the mouth, chewing, swallowing and so on, you should continuously be mindful of all that as you eat. All this is in accordance with what the Buddha discoursed on, namely in eating, drinking, chewing, tasting, one does so with full awareness,²¹ and which Mahāsi Sayādaw had further explained and instructed as the task of vipassanā meditation…”

Daw Kin Thwe continued meditating according to the above instruction. About fifteen days later, while mindfully taking her meal, she perceived a very putrid odour. Wondering what it was, she reflected for a moment; then thought that it must be due to her tumour.

“If that is the case, your tumour is probably disintegrating,” I reminded her and continued to encourage her. Sure enough, just as I said, her large tumour was gradually disintegrating and it eventually vanished from her belly. Daw Kim Thwe was overjoyed. When she went back to her doctor for another medical examination, he was taken aback.

“Ha! Your tumour’s no longer there! Whatever did you do?” he asked in surprise.

“I meditated at the Mahāsi Meditation Centre, see. Though you said that if I did I might die, not only am I not dead now, but even my tumour has completely disappeared!” she triumphantly replied.

The doctor exclaimed, “Hey, is that so? Your Dhamma is truly a wonder, huh!” The doctor was an Indian, it seems.

2. Monk cured of tumour in the abdomen

A bhikkhu of eight vassa from Kim Byar Village, Shwe Bo Town, arrived in Mahāsi Meditation Centre, Rangoon, and commenced meditation on the 3rd waxing day of Tasaungmone, 1336 BE [some time in November 1974]. His name was U Sobhana and he had suffered from a tumour in the abdomen ever since he was a seventeen-year-old novice (sāmaṇera). After meals the tumour would press against the right side of the abdomen and become tight so that it was almost impossible to sit, he said. If he had no alternative, he would have to press his hand against the part under which the tumour was situated, and then only could barely sit. Many told him that he had to be hospitalised to surgically remove the tumour, but he was afraid of being operated on, and so just left things as they were.

During his first retreat at Mahāsi Meditation Centre, Rangoon, he did not lie down after meals but instead headed straight for the sīmā Hall to sit and continue meditating. While sitting, he pressed his hand on the tumour spot. After about twenty days of ardent effort, he no longer had to press against the tumour spot for he found that he could sit very comfortably after meals and with good mindfulness too. Only then did he realise that his tumour had vanished. He could sit for over three hours and for a period of five days he was able to maintain unbroken mindfulness throughout the day and night without even lying down to sleep. On the 45th day into his retreat he qualified for Nyanzin.²² Even now (in the late ’70s), at Mahāsi Meditation Centre, Rangoon, U Sobhana is carrying out his duties as a resident bhikkhu.²³ His tumour never recurred and he is ever in good health.

3. Large tumour disintegrates

Fifty-four-year-old U Aung Shwe of Daing Wun Kwin, Moulmein, had a large tumour in his abdomen. When he visited a doctor for a medical examination, he was informed that an operation was necessary. Instead, with the support of the Dhamma which is a dependable source of refuge, he arrived at Mahāsi Meditation Centre, Rangoon, and started meditation on the 5th waning day of Nayone, 1330 BE [around June 1968]. One day while meditating he experienced, through insight, a sudden bursting of the tumour in his abdomen followed by its disintegration and the rapid discharge of gushing blood. It was as if he was actually hearing it with his ears and seeing it with his eyes. He was completely rid of the tumour. Continuing meditation to the satisfaction of his teachers, he eventually attained all the vipassanā insights to full completion. Even till this very day he is healthily and happily rendering his service to the Sāsana in both fields of study (pariyatti) and practice (paṭipatti).

4. Cured of arthritis of the knee

On the 1st waning day of Wagaung, 1313 BE [around August 1951] forty-year-old Ko Mya Saung arrived at Myin Gyan Yeikthā, a Mahāsi branch meditation centre, and commenced meditation under the resident Sayādaw. Ko Mya Saung had suffered from arthritis of the knee for five years. Despite treatment by various doctors, the ailment was not cured. He was stirred by saṃvega and came to Myin Gyan Yeikthā to meditate. While meditating, his knees swelled, and the more the pain was noted, the more intense it grew. As Sayādaw had instructed, he persisted in noting it unrelentingly. The pain became so excruciating that tears rolled down his cheeks and his body was thrown forwards and backwards or suddenly jerked upwards in the most awkward manner. This lasted for about four days. And while thus engaged in mindful noting he saw, in a vision, his knee together with the bones breaking apart. In great alarm he screamed, “Haw! Do it man! It broke! My big knee broke!”

After that incident he was so scared that he did not dare to meditate. However, with Sayādaw’s encouragement, he resumed mindful noting. Eventually the swelling and pain completely disappeared and Ko Mya Saung was never troubled by it again.

5. Sayādaw cured of occult affliction

Fifty-five-year-old Sayādaw U Sumana from Nga Da Yaw Village Monastery, north-west of Myin Gyan, arrived at Myin Gyan Yeikthā on the 2nd waxing day of the 2nd Waso, 1319 BE [around August 1957], and meditated. The Sayādaw suffered from unbearable discomfort due to a large lump in his belly and although he had been able to obtain some temporary relief through the treatment by various doctors, he was unable to get it completely cured. Spurred by saṃvega, he decided to meditate.

It seems that in the course of his retreat, he was pushed, pulled, nudged, jolted and constantly molested by four spell-casting witches. He related that he could even see their shapes and forms, and when he persisted to make incessant note of them, he experienced unbearable constriction and pain in his belly. Terrified, he started to make preparations to go home. Then the Myin Gyan Yeikthā Sayādaw said to him, “Don’t be afraid. The affliction will surely vanish in time. Note mindfully to overcome it. Noting mindfully means developing the seven causal factors of insight (satta sambojjhaṅgā)… If you’re really scared, we’ll post a guard to watch over…” Soothed by his teacher’s words of assurance and encouragement, Sayādaw U Sumana changed his mind about going home and strove on. Early one morning, an intense pain inside the abdomen prompted him to empty his bowels. While doing so, he noticed greenish, reddish, yellowish and bluish lumps and mucus being excreted. His body felt light and nimble; thenceforth, he was completely cured of his affliction. He was so immensely satisfied and overjoyed that he quickly went up to his teacher at the Yeikthā and exclaimed, “My afflictions are all gone! Completely gone! They’ve vanished!” Thus Sayādaw U Sumana started meditation on the 2nd waxing day of the 2nd Waso month, and within the following month of Wagaung he was completely healed. Restored to normal health, he continued to strive on at the Yeikthā till the end of the Rains Retreat.

6. Old man cured of asthma

Seventy-year-old U Aung Myint of Le Thit Village, east of Myin Gyan, commenced meditation at Myin Gyan Yeikthā on the 7th waning day of Tawthalin, 1326 BE [around September 1964]. He had suffered from asthma for about thirty years. Handing over thirty kyats,²⁴ which he had brought with him, to Myin Gyan Sayādaw’s kappiya,²⁵ he requested of his teacher, “If I die, please make use of this money to perform my funeral rites.”

“Don’t you worry, dakāgyi! ²⁶ I shall take care of everything,” Sayādaw assured him. “Just try hard and strive on!”

Six days later as a result of meditating, his condition became much worse. For two whole days he could not even eat rice gruel because he had fits of breathing difficulty, which greatly weakened him so that he slumped over like a hunch-back while sitting. Other yogis who had gathered around to help him thought that the old man was about to die and informed their teacher. Sayādaw arrived and gave some words of encouragement as he instructed the aged yogi to note his tiredness. U Aung Myint faithfully began noting, “tired, tired.” After two hours the tiredness was replaced by a sense of ease and comfort.

About a week later he had a relapse and again for three whole days was unable to eat. Many thought that he was surely going to die. Sayādaw once again assured him that the affliction was about to vanish and, after further encouragement, instructed him to endeavour to be mindful. Hearing that, the people around the aged yogi smiled incredulously and commented, “He’s almost at the point of death! How can he be mindful any longer?”

As for U Aung Myint, while intently being mindful—just as Sayādaw had encouraged—he saw with insight, in the mind’s eye, his belly burst open and mucus and lumps of green, red, yellow, and blue matter issuing forth.

“My big belly’s burst open, sir!” he cried out.

After that he continued noting mindfully according to Sayādaw’s instructions, and was never again bothered by asthma, for it had completely vanished. Because U Aung Myint had once been a bhikkhu who later disrobed, his acquired preaching ability enabled him to show the Dhamma ²⁷ to friends and relatives back at home. Even till this day (1973) he is still alive and in good health.

7. Cured of leukodermic rashes, itch and pain

On the 4th waning day of Tazaungmone, 1336 BE [around November 1974], twenty-year-old Maung Win Myint of 90 Upper Pan Zo Tan Road, Rangoon, commenced meditation at the city’s Mahāsi Meditation Centre. Eventually he was cured of his skin disease. This is his testimony:

When I was just over sixteen years old, I went to stay in Shwe Gyin. There I ate various types of venison, the flesh of wild cats, snakes, iguanas, and other sorts of smelly meat, with little discretion. A year after eating those meats, my whole body including the arms and legs, began to itch and become painful. My blood turned unclean and impure. My complexion was spotted with white patches of leukoderma. Every night I constantly had to get up to scratch the irritating itch, which seemed to be erupting throughout the night. Because of this disease I could not make progress in school and fell behind in promotion.

I went to Dr M J for exactly three months of treatment without missing a single day. I had to take medicine and an injection daily. Each shot cost me eight kyats. I was not cured.

Then I went to a skin specialist, Dr K L, and again was given injections and medicines. After two months of treatment nothing much changed. Medical fees came up to ten kyats per day. I could only enjoy myself for brief moments when attending theatrical shows and other entertainment. Most of the time I felt pretty depressed by the irritating itch. From the age of sixteen until twenty I had to endure these sensations without even getting a single day of mental ease or comfort.

On 2 December 1974, my grandfather sent me to this Yeikthā so that I could start meditation. Within two minutes after I sat down the itch came. It did not disappear, though I mindfully noted it. On 11 December the itch grew so intolerable that I fled from the Yeikthā, but even back at home the itch persisted, and I alternated between scratching and trying to be mindful. Dawn soon broke and Grandpa called to send me back to the Yeikthā. Though not really wanting to follow him, I had to come back. In the afternoon I went up to Sayādaw and told him that I had not been able to be mindful because the itch was unbearable.

“Note to overcome it! The itch will eventually disappear. When you take an injection, you have to pay for it and you will feel its pain. If you just note mindfully, you don’t need to spend anything and you don’t feel any pain at all!” Sayādaw answered in encouragement. Then he went on to urge me, “Be patient and intently note the itch with uninterrupted mindfulness! Eventually it will vanish.”

Inspired, I went back to sit for the 4.00 ‒ 5.00 pm session. Barely five minutes had gone by when the itch came. Resolute in overcoming it, I duly noted “itching, itching,” and sure enough, eventually it disappeared! I was overjoyed. During the first sitting session of the night, from 6.00 ‒ 7.00 pm, the itch returned. This time it was really intense, and it caused tears to fall. Though I was persistent and firmly continued to note it, quivering and shivering like someone possessed by spirits, the itch did not go away. Then I brought my attention back to the rise and fall of the abdomen, and began watching and noting that instead. While I was doing so the itch suddenly and miraculously disappeared! I haven’t the slightest idea how that happened.

In the days that followed, every time that itch occurred, it would eventually vanish upon being noted. I was very happy and my enthusiasm for sitting was tremendously strengthened. On the 20th the itch came again. At first it simply would not go away though I noted it. Tears fell, and I was sweating. Suddenly, the entire body was seized by convulsions, but I was resolute, and it was only through persistent noting that the itch finally vanished. How that could have happened, I simply had no idea at all!

During the 3.00 ‒ 5.00 am sitting session on 10 January 1975, my legs, arms, back and head were itching badly. With mindful noting, the itch disappeared, but later, while I was still engaged in the process of mindful noting, the en-tire body suddenly became itchy. On being firmly noted, all itching sensations abruptly vanished, as though leaving the body through the crown of the head. The uncomfortable heat that I had also been feeling disappeared too in a similar way. At around 11.00 am, as I was sitting outside for a while just before bathing, a stray dog came to sit beside me. I chased it away because I could not stand its stench, but the stink was still there even when I entered my room.

“Wherever is the stink coming from?” I wondered, and started to look around, only to discover that my own body was the very source of the stench! Quickly I bathed, washing and scrubbing my body with soap, but to no avail, for the foul odour could not be eliminated. For exactly two days, until the 12th, I stank, but because I felt rather embarrassed, I did not tell Sayādaw about it at that time. After that, while I was mindfully noting it, the dog-stink vanished. All the itching and irritating sensations also disappeared. My blood became clear and pure again, the white patches of leukoderma vanished, and my skin was restored to its normal fresh, smooth and pleasant complexion.

Afterwards when I went to the Dermatological Hospital for a medical check-up, the nurses were greatly surprised, for they had once said, “No matter how many injections you are given, this disease might never be cured!” No wonder they were surprised! Then when they asked how the disease got cured, I explained, “I went to Mahāsi Meditation Centre and meditated. As I continuously observed and noted all the mind and matter arising, the disease vanished altogether.

“Hey!” they exclaimed, full of praise, “This Dhamma is really powerful, huh!”

This is the testimony of Yogi Win Myint who had suffered from an itchy skin disease called leukoderma for three years, as related to Sayādaw U Sujāta.

Cases from Sayādaw U Nandiya

Cases from Sayādaw U Nandiya

(of Satipaṭṭhāna Yeikthā, Taw Ku Village, Mu Done Township)

Abandoned incurable cured

HEN U Nandiya, a meditation teacher, was still a layman he was afflicted by numerous illnesses. He had suffered for years from hemiplegia, hydrocele and frequent spells of giddiness. Abandoning him as an incurable, native doctors refused to treat him.

HEN U Nandiya, a meditation teacher, was still a layman he was afflicted by numerous illnesses. He had suffered for years from hemiplegia, hydrocele and frequent spells of giddiness. Abandoning him as an incurable, native doctors refused to treat him.

After becoming a bhikkhu, he had a serious attack of fever and four months of medical treatment brought only slight improvement. Mustering up as much strength as possible from the little left, he resolutely approached Sayādaw U Paṇḍava of Mahāsatipaṭṭhāna Monastery, Moulmein for meditation.

However, he did not immediately commence his retreat upon arrival because he was feeling rather weak, but while waiting to recover strength he again contemplated, “Old age, pain, and death do not put off the days or tarry. If I keep postponing I will surely fall into the abyss of foolishness. On this very day I shall start meditation!”

So, with a resolute mind he began to meditate right on that day. He did not speak to a single person, locked himself up in his room and resolutely meditated. He relentlessly watched and noted all sensations that arose, with diligence.

By not changing postures frequently and being patient, he could steadily remain attentively mindful for longer and longer stretches of time—from an hour to two, two to three, three to four hours, and so forth. By the time he was able to do so for a six-hour stretch, the coarser painful sensations had diminished, and when he could remain immovable and mindful in one single posture for twelve hours, all the finer sensations completely vanished. In the most natural way he was relieved of all evident painful sensations as well as the various illnesses he was then suffering from. It should be noted with conviction that this healing and relief resulted from great fortitude in the persistent application of intent mindfulness.

It may justly be said that it is extremely difficult to find such rare qualities of great fortitude and diligent effort as were found in U Nandiya. Any painful sensation whatsoever that occurred was never ignored, but made the very object of intent mindfulness; not with the attitude of “I simply will not stand it if I don’t win.” Instead, with the view of “My task is to be mindful of whatever occurs,” he continued noting mindfully. And in doing so he was indeed eventually relieved of all painful sensations.

Fifteen years ago when he had 17 Rains (vassa), U Nandiya started showing the Dhamma ²⁸ to yogis. The method shown was of course, based on Mahāsi Sayādaw’s way of meditation. Special encouragement was given to maintain any one posture. By instructing yogis intending to change positions to be mindful of those very initial intentions to shift, before they actually changed, he gradually lengthened the time of a posture from fifteen minutes to half an hour, and so forth. This prolongation of a posture may seem to be a tall order—to be mindful to the extent of “Shouldering an unbearable burden.” Not so. As the Burmese saying goes, “If strength is inadequate, lower your pride.” So too, if yogis were unable to continue being mindful, they could change postures and then be mindful.²⁹ In this way, yogis were able to strive for an hour to two, two to three hours, and so forth, for increasingly longer periods. They were also able to be mindful of whatever sensations that occurred.

Some yogis could remain mindful in a single posture for twelve hours and even up to fifteen hours without shifting their bodies or limbs. Some were instructed to practise more in postures that were appropriate for their states of health.

For instance, those suffering from giddiness and hemiplegia were instructed to be mindful mainly in the standing posture, while those suffering from piles, mainly in the sitting posture. Accordingly, when they could remain mindful for six hours or more, they were relieved of their illnesses. As they noted mindfully their postures became much more stable. Subsequently all the painful sensations and ailments completely vanished and they felt great ease and comfort.

Yogis were recommended to start being mindful in the sitting posture. When unable to prolong mindfulness in that position they were advised to be mindful while walking. So too from walking to standing and from standing to lying, but since the yogi is most likely to fall asleep in the lying posture, instructions were given to start by being mindful while sitting and then change postures as in the order listed above, maintaining each posture for one to two hours. While thus engaged in unbroken mindfulness and the changing of postures, the yogi’s body will become heavy, unmoving and stiff as a corpse as he lies stretched on the bed. He will not fall asleep. Instead, unclouded by avijjā (not-knowing), but indeed with mindfulness and knowledge, he will remain still and calm, noting without any interruption. This tranquillity may last for one whole day or even as long as a day and night. Yogis have recounted personal experiences of discovering their illnesses and painful sensations actually disappearing, with the body feeling very light when they moved from the still and mindful state.

Below are some cases, from among the many, of yogis who experienced the disappearance of illnesses and pain through gradual prolongation of a posture and in the case of male yogis, with Sayādaw U Nandiya nearby, personally watching over the frightened ones.

1. Cured of bronchitis and malaria

Sayādaw U Vaṃsapāla of Dhammikāyone Monastery, Kyaik-Kar Village, Mu Done Township, had suffered from giddiness, asthmatic bronchitis and malaria since 1950. Though he had recourse to what he thought was suitable medicine, they gave only temporary relief. The ailments recurred every now and then.

Spurred by saṃvega he meditated, at first for a period of two weeks. In the month of Tawthalin, 1335 BE [around September 1973], he again meditated for a second time for about three months. He was able to be continuously mindful through the sitting and standing postures for twelve and eight hours respectively and was appreciably relieved of the ailments and pain.

Thus inspired, he returned to strive for the third time so that the ailments might be completely cured. Indeed, within a week he could be continuously mindful for fourteen hours in all the three postures of lying, sitting, and standing. Giddiness, asthmatic bronchitis, malaria and all the former painful sensations vanished once and for all. This third meditation retreat lasted for five months and thirteen days.

One day while Sayādaw U Vaṃsapāla was thus engaged in being mindful of painful sensations, the gong for lunch was struck. In spite of that he did not shift but continued observant noting. Later in the night, after the pain had vanished, unpleasant sensations of giddiness, hunger and heat occurred almost simultaneously. With mindful noting of those very sensations, giddiness disappeared after about two hours, followed by hunger and finally heat.

2. Cured of a host of ailments

Senior monk U Uttara of Ga Mone Monastery, Tagun Village, Mu Done Township, had been afflicted for years with giddiness, heart ailment, piles, urinary troubles, jaundice, ache in the buttocks, and lumbago. In the year 1975 he entered the Rains in Mahāsatipaṭṭhāna Monastery and meditated. He was almost at the point of tears as intense and unbearable pain occurred. Instructions were given to be mindful of it just as it happened. At first he was only fairly able to note mindfully, but day by day, mindfulness improved. By the time he was steady in his posture, the painful sensation had diminished in intensity; and when he could be mindful for a continuous stretch of six to seven hours, all the above-mentioned painful illnesses vanished. Today he lives quite comfortably in his resident monastery, continuing to practise mindfulness with no need for massage.

3. Cured of urinary problem

A resident bhikkhu, U Ñāṇadhaja of Mahāsatipaṭṭhāna Monastery, Taw Gu Village, Mu Done Township, suffered from constricting pains in the abdomen. A doctor advised an operation.

“Before going for the operation, try meditation!” Sayādaw U Nandiya advised him.

“I frequently feel the need to urinate every now and then. Yet when I do go, only a little bit comes out.”

“Your belly pain could probably be due to this,” said Sayādaw U Nandiya encouragingly, and instructed him to be mindful. “Whenever you feel like wanting to urinate, you should intently note ‘wanting to urinate, wanting to urinate’.”

He noted mindfully as instructed and expelled a total of twenty-seven tiny white stones in succession. U Ñāṇadhaja was thus completely cured of abdominal pain and the frequent urge to urinate.

4. Complete cure for a bhikkhu

U Sin, a late-comer into the Saṅgha who had been ordained under, and was then residing with his preceptor (upajjhāya) U Nandiya, suffered from giddiness, fatigue, constricting pains and was hard of hearing. One day, meditating according to Sayādaw U Nandiya’s instructions, he was able to be continuously mindful for about six hours; whereupon the painful sensations diminished, and he felt quite relieved. With continuous observant noting he was completely cured. All those painful sensations never occurred again even when he maintained mindfulness for increasingly longer periods of time, right up to twelve hours.

5. Cured of giddiness

Eighteen-year-old Ma Than Yi, daughter of Tagun villager U Thein Hlaing, had suffered from giddiness for over ten years. She came to the Yeikthā, and with faith and diligence, meditated intently. On the third day she was able to be continuously mindful in a single posture for about three hours. She could then also mindfully note her giddiness. Each time it was noted, the giddiness vanished. Later on, though she was mindful for prolonged periods, the giddiness never occurred again. She had been completely cured.

6. Cured of ten-year ailment after ten days

Twenty-year-old Ma Khin Than, daughter of Taw Gu villagers U Ngo and Daw Win Kyi, had suffered from constricting pains in the abdomen for over ten years when she came to the Yeikthā to meditate. On the third day when mindfulness could be maintained for three hours, she vomited some lumps from her belly. She also had diarrhoea. Instructions were given to be mindful of her symptoms as they happened. After ten days the ailment never occurred again, right up till today.

7. Abdominal pains disappear

Sixty-year-old U Win of Naing Hlone Village had suffered from constricting pains in the abdomen for many years when he arrived at the Yeikthā to meditate. At about 8.00 pm on the third night, as he was being mindful according to instructions, he vomited about two spittoons of hard solid matter.³⁰

The abdominal pain disappeared too. With his continued observant noting, the sickness never occurred again.

8. No more dependent on a masseur

Seventy-year-old U Tut of Tagun Daing Village suffered from giddiness and pains; so he always had to have a masseur standing by to attend to his needs. He was also afflicted with piles and bronchitis. He came to the Yeikthā for meditation. At first he was able to be mindful for only about an hour. He prolonged it progressively to up to four hours. All the various painful sensations gradually diminished until eventually they vanished completely.

9. Cured of a stomach tumour

Daw Ngwe Thein of Tagun Village had intestinal colic and a tumour in her belly. Medicine dispensed by a clinic did not cure her ailments; so she went to the General Hospital for a check-up and was told by the doctor that she would have to undergo an operation. She was already seventy-five years old and because of weakness she did not dare to undergo the operation.

“If I die, let me die with mindfulness,” she said, and came to the Yeikthā for meditation. At the beginning, she could not be mindful for long in a single posture, but was gradually able to prolong her mindfulness. As much as she could be mindful, her ailments diminished too. When she was able to maintain mindfulness in a single posture for a five to six-hour stretch, all her sicknesses vanished. Now (1975) at the age of seventy-eight, it has been three years since they disappeared, never to recur.

10. Another cured of a tumour

Fifty-five-year-old Daw Sein Ti of Kyaik Kwe Village suffered from constricting pains due to a tumour in the abdomen. For the past fifteen years she had had to take soda. She came to the Yeikthā for the Dhamma therapy prescribed by the Buddha ³¹ and was mindful according to the teacher’s instructions. Day by day, as her posture became steadier, the intensity of the illness diminished too. When she could be mindful for a seven-hour stretch, the illness and all painful sensations completely vanished. Now (1975) she is already sixty, and no longer needs to take soda, nor are there any more constricting pains in the belly. Her meditation retreat lasted sixteen days.

11. Chronic pains of forty years eradicated in a retreat

Ever since she was thirty, Daw Ma Le of Tagun Daing Village had suffered from abdominal pains. In the past, meditation centres ³² had not yet been established. So the thought of meditation did not occur to her. When she was seventy years old, a meditation centre near her village had become quite prominent; so one day she went and meditated. Just like most people, she could only be fairly mindful at the beginning, but practising according to the teacher’s instruction to gradually prolong and maintain the posture, she could eventually be mindful for five to six hours at a stretch. Then her illness vanished. Now (1975) she is already eighty-eight and her illness has never recurred.

12. Cured of illness of twenty years

U Yasa, a resident bhikkhu of Mahāyin Monastery, Kun Dar Village, Mu Done Township, had suffered from giddiness and hydrocele for over twenty years when he arrived at the Yeikthā to meditate. Only when he reached the stage where posture could be maintained for four hours did his illness diminish in intensity, giving some relief. As he carried on noting mindfully, they completely disappeared. And when he could be continuously mindful in the standing posture for twelve hours, the sickness never recurred.

13. Cured of paralysis

Daw Khyi, a lady from Kant Baloo Town, Shwe Bo District, had fallen from a tree and a leg became partially paralysed. At Mahāsi Meditation Centre, Rangoon she met a nun from Myowa Mahāsatipaṭṭhāna Monastery, Moulmein and followed her via Moulmein to arrive at Taw Gu Village Yeikthā. At first she still could not be very mindful. However, as she gradually improved and could be mindful for four hours at a stretch, her disability and pain diminished in intensity, giving some relief. About a month later she was able to be continuously mindful for seven hours and was completely healed of hemiplegia.

14. Persuaded by relatives to meditate

Before U Nandiya established Taw Gu Village Yeikthā, he was residing at Mahāsatipaṭṭhāna Monastery in Kok Karait Town teaching the Dhamma. Around the year 1963, there was a woman in the town called Daw Kyawk Khin who suffered from ascites, which swelled up her belly as though she was pregnant. She went for a medical check-up, and the doctor said, “We must operate. It will cost about a thousand kyats, but we do not guarantee it will be cured.”

Because of fear, she did not go for the operation, but because of her relatives’ encouragement and pressure on her to meditate, she arrived at the Yeikthā quite against her own wishes.

“There are bold ghosts and fierce spirits of the departed (peta) in that Yeikthā, and they could very well scare the wits out of you!” This rumour had gone round and Daw Kyawk Khin had heard it too—only too well. No wonder she did not want to come!

Upon her arrival, Sayādaw U Nandiya gave instructions to be mindful in the lying position, the posture most appropriate for her condition. As she mindfully noted her posture, her body felt increasingly heavy until it became immovable. Thinking that she was being possessed by a bold ghost, she lost her mindfulness.

“I’ve been possessed by a bold ghost! I’m going to die! You all have come to kill me, huh! I’m not staying any longer! Send me back,” she cried hysterically as she struggled in a frenzy to get up. Angry at all those people who had sent her to the Yeikthā, she scolded them roundly.

“Don’t leave, dakamagyi. Don’t be angry.³ Well, do apologise for what you’ve unwittingly said, of course. You’ve been very fortunate to be able to come and meet me, you know, and I’m regarding the situation on an intimate brother-sister basis. If you don’t want to lie down, don’t, but listen to what I have to say. Well, you can walk over there for a while. When feeling heavy, note ‘heavy, heavy,’ and if you feel light, note it as ‘light, light.’ Do keep on noting for an hour or two; for as long as you can. If you can’t walk any more, just stop and stand over there. When you feel heavy, note ‘heavy, heavy’ and if it’s light, note ‘light, light.’ Do keep noting for as long as possible. Then if you can’t stand any longer sit by the side of your bed and note for a while. When feeling heavy, note ‘heavy, heavy,’ and when light, note ‘light, light’ for as long as you can. If again you can’t sit any more lie gently on the bed and if you feel heavy, note ‘heavy, heavy.’ If you feel light, note ‘light, light.’ Just carry on noting, that’s all. If you should fall asleep, let it be! When you’re lying down, don’t be afraid of anything! I will send loving-kindness (mettā) and watch over…” Thus Sayādaw coaxed her to keep on noting.

The dakamagyi, who was afraid to lie down, finally assumed the lying position because she could no longer be mindful in the other three postures. With the intention to sleep, her whole body became heavy and immovable and she was quite calmly mindful. However, instead of falling asleep, she maintained mindfulness for three hours and the whole body became light. Her distended belly also deflated and regained its normal condition. Upon getting up she reported joyously to Sayādaw, “I’m so amazed, Bhante,³⁴ really amazed! My whole body has become so light, Bhante! My belly has gone down too, Bhante!”

15. Sickly after a fall

A boy named Yang Aung of Taw Gu Village suffered from constricting pains, headaches, and tumours in the abdomen after falling down from a tree. Nothing much came out of the healing efforts made by native doctors. An elder monk (thera) even pronounced, “Liver failure, incurable.” The complexion of his whole body was very sickly. He came to the Yeikthā and while meditating felt something inside the abdomen, like a top spinning. It also ached. After about ten days a sound like “gayoke” came from the abdomen. “It’s burst open,” he thought. At the same time a rotten smell emitted from his mouth. There was saliva and heat. On another day he felt light and relieved. When he could be mindful in either one of the sitting or standing postures for a continuous stretch of six hours, all the illnesses vanished. He was also able to be mindful sitting for six hours followed by another six of lying down at a stretch. Later he became a sāmaṇera and until today (14th waning day of Tabodwe, 1338 BE, i.e. around February 1976) he is still residing in Taw Gu Yeikthā.

16. Mentally deranged boy

A boy named Maung Than Win from Moulmein became mentally deranged, speaking and doing as he liked. An exorcist could not help him. The Psychiatric Hospital was no help either. In spite of taking medicine prescribed by the doctor from the General Hospital, there was no improvement in his condition. He finally came to meditate at Taw Gu Yeikthā. Gradually his mind calmed down. When he could stay mindful in a single posture for about six hours, he was completely cured of his condition. Right now, i.e. l4th waning day of Tabodwe, 1338 BE [around February 1976], he is still a sāmaṇera.

17. Miscellaneous cases

- Ma Kyin Myaing of Moulmein was cured of piles while noting mindfully and continuously in the four postures, as instructed by the teacher.

- Daw Pyone of Mu Done Town was cured of deafness while meditating.

- Maung Me of Taw Gu Village was cured of hydrocele and constricting pains in the abdomen while noting for four hours in the sitting and standing postures. He had suffered from these ailments for three and ten years respectively. He no longer needs massage as in the past.

- U Hnyunt, a gentleman from Kawk Pi Daw Village, had suffered from hydrocele for about ten years when he came to the Yeikthā to meditate. He could be mindful in the standing and sitting postures for three hours. Within seven days, he was cured of the affliction.

- Ma Kun Me, a lady from Naing Hlone Village, had suffered from partial paralysis of the leg and high blood pressure for about ten years. She came to the Yeikthā, meditated and as a result, was cured of these ailments.

- Daw Them Tin of Kawk Pi Daw Village was cured of her month-long partial paralysis of the leg through mindfulness, within a week after arriving at the Yeikthā.

- Daw Dhammavatī, a nun from Ka Lawk Thawk Village, came to meditate at the Yeikthā. She was mindful through all the four postures, and could note observantly for as long as twelve hours in the standing and sitting positions. She was cured of the piles, which had afflicted her.

- Sixty-year old U Waw of Taung Bawk Village came to meditate at the Yeikthā. Before seven days, he was cured of partial paralysis of the leg, a condition which he had suffered from for about five years.

Note by Ven Mahāsi Sayādaw

The above report (nos. 1 ‒ 17) was submitted to Mahāsi Sayādaw by U Nandiya of Mahāsatipaṭṭhāna Yeikthā, Taw Gu Village, Mu Done Township in the month of Tabodwe, 1338 BE [February 1976]. Sayādaw U Nandiya himself was able to remain continuously mindful while standing or sitting for more than twelve hours at a stretch, and in the lying posture, he could remain mindful for twenty-four to twenty-six hours continuously. It is said that until he got up from the bed there was no shifting of body and limbs, his body posture remaining just as when he first lay down.

Yogis who came to him were also typically instructed to prolong their observant noting, following his own example. Especially typical were instructions to maintain observant noting while standing for three hours initially, then progressively prolong the time. Presently he is already ninety years old with thirty-two Rains, still healthy and able to move about. In his foregoing report only cases of healing were given. Occurrences of special insight knowledge were not described. However, it should be noted that the healing of serious illnesses comes about through the power of strong [i.e. highly developed] enlightenment factors associated with knowledge of arising and passing away (udayabbayañāṇa) and subsequent insights occurring in yogis who are able to maintain unbroken mindfulness in a single posture for prolonged periods of three hours and more.

Some Remarkable Cases: Sayādaw U Paṇḍita

Some Remarkable Cases: Sayādaw U Paṇḍita

1. Old ailments healed within a month

IFTY-year-old Daw Khin Sein of 32, Race Course South Side, Ta Mwe, Rangoon, had been afflicted by a lump in the abdomen from the age of forty-five. This caused painful stiffness in the upper chest (epigastrium), headache, giddiness, dyspepsia and other disorders. These symptoms would be aggravated if she ate food that was difficult to digest. Treatment with traditional, western and various medicines had no effect.

IFTY-year-old Daw Khin Sein of 32, Race Course South Side, Ta Mwe, Rangoon, had been afflicted by a lump in the abdomen from the age of forty-five. This caused painful stiffness in the upper chest (epigastrium), headache, giddiness, dyspepsia and other disorders. These symptoms would be aggravated if she ate food that was difficult to digest. Treatment with traditional, western and various medicines had no effect.

Finally her own son, a doctor, suggested that surgery might be necessary. However, because Daw Khin Sein was frightened by the thought of having to undergo an operation, or perhaps because the desire to meditate had just arisen, she arrived at the Yeikthā on the 8th waxing day of Hnaung Tagu, 1337 BE [April 1975].

After a few days of meditation, she suffered a serious attack of the symptoms caused by the lump. “Coming to the Yeikthā was a mistake,” she lamented then, and even thought of fleeing the Yeikthā. Besides, the symptoms of an old injury in her big toe caused by a tough sundri ³⁵ log during her younger days recurred, bringing her to the point of tears. An ache in the upper arm which she had suffered from two years ago also recurred, quite intensely too.

Although the recurrence of these old ailments tormented her severely, she carried out the teacher’s instructions with diligent effort. Then, while engaged in intent mindfulness, the old wound caused by the log and the pain in the upper arm completely vanished. Her body felt cool and comfortable, without any sign of those ailments. So there was an increase in enthusiasm for meditation, and on the twenty-eighth day into the retreat, the large lump which had gone right up till the upper chest and caused so much discomfort, moved downwards. It then disintegrated with a ‘phyoke!’ sound, and dissolved. Consequently, the blood discharged from the disintegration of the large lump soiled her lower garments, so that they had to be frequently changed in the next few days.

Thus she also had a penetrative insight into the heavy burden of the body. And though she had thought that this great discharge of blood would make her weak; on the contrary, she felt surprisingly much stronger than before. She felt comfortable and experienced clarity of mind and body.

With the disintegration of the large tumour, the accompanying ailments were completely cured too. So apart from expressing her thanks to the Sayādaws she was also filled with boundless gratitude for her husband who had allowed her to meditate. After that she continued meditating with keen faith to the satisfaction of the Sayādaws and attained extraordinary vipassanā insights. Though in the past she had to be careful about her choice of food, from that time on she could eat as desired, no longer having to be selective. Within ten days after returning home, she went for a medical checkup and was informed that an operation was no longer necessary Till today [1977], Daw Khin Sein is still healthy, managing social and spiritual affairs much better than ever before.

2. Hypertension of 29 years cured in a single retreat

Fifty-nine-year-old Daw Than, who lived in the Labourer Quarters at Mahāsi Meditation Centre, Rangoon, had suffered from hypertension since the age of thirty. Treatment with traditional, western and all sorts of medicines gave some relief, but did not result in a total cure. As the hypertension was persistent, she had to check her blood pressure daily. She experienced much body and mental suffering. Though there was a desire to meditate, she did not do so, thinking that with her bad state of health she would not be able to be mindful.

However in the month of Kasone, 1337 BE [May 1975], because the desire became very strong, she strove for vipassanā Dhamma at the Yeikthā, which was also her own home. Nothing very significant occurred at the beginning, but about five days into the retreat, her blood pressure was so very high that she was unable to lift up her head. And when her children from home called to take her for medical treatment she thought, “It would be much better and nobler for me to die while meditating.” So she did not return home, but continued to strive on.

While sitting mindfully, she swayed, leaning as though about to fall over. The whole body was heavy and sluggish. Thus engaged in being continuously mindful of whatever was occurring—following the teacher’s instructions not to allow any slip in mindfulness—she felt something burst within her chest. Lights emitted from her whole body which was was engulfed in heat. After that her meditation was very good. At the beginning she had to try quite hard to sit mindfully even for an hour. However, after that incident, for the later part of her retreat, she could sit mindfully for as long as two and a half hours; yet it felt as if she had been sitting joyfully and comfortably for only a short moment without any tiredness at all. The whole body felt light and painful sensations were absent for they had been extinguished. She continued striving to the satisfaction of the Sayādaws till she ended the retreat and upon leaving the meditation centre no hypertension was detected. Previously her face was slightly swollen and the head always felt heavy; now there was no longer such discomfort. Upon checking, she found no indication of hypertension. In a written statement Daw Than declared that she was completely cured of hypertension through the ‘grace’ of vipassanā Dhamma. Presently, she is as healthy and well as ever.

3. Heart surgery bypassed in ten-day retreat

Daw Myint Myint Kyi of 11 Shan Lein Road, San Kyaung Section, Rangoon, had been tormented by heart disease since the age of twenty-three. In the year 1328 BE [1966] she went for a medical check-up and was informed that she had to undergo an operation in fourteen days’ time. Aiming to be established in the Three Refuges—should she die while being operated on—she invited the Saṅgha headed by Mahāsi Sayādaw for a meal. She offered gifts, took refuge and precepts and performed the water ritual in the dedication ceremony.³⁶ At that time, Mahāsi Sayādaw remarked that it would be good if she could meditate before going for the operation. So she came to the meditation centre and after five days she felt as though the whole body was filled with pus. Her heart ached. Since she could not be mindful while sitting, she walked mindfully. Then after four to five hours of walking mindfully she sat to meditate at 10.00 pm. About twenty minutes later she was startled by an explosive sound; she felt her heart burst apart and her arms and legs flung open awkwardly. She also ‘saw’ a marble-sized lump bursting. After that though she continued observant noting, except for a good feeling in her posture, nothing else happened. Meditating for another five days proved to be just as good.

After only ten days of meditating, she had to go back for a medical check-up whereupon the doctor declared that there was no longer any need for an operation. After that whenever the slightest pain occurred, mere mindfulness of it would result in it disappearing. This April (1977) when she went for a medical check-up at the hospital, the doctor said that the hyper tension had been cured completely. Daw Myint Myint Kyi herself also said that she felt really good without the slightest discomfort. Her hypertension had been completely cured by mere observant noting, without having to go through any surgery.

Special Cases of Cures: Sayādaw U Saṃvara

Special Cases of Cures: Sayādaw U Saṃvara

1. Leg injury of six years cured within a month

AW Thein Khyit of 119, 27th Street, Rangoon, fractured her ankle ³⁷ while nursing her grandchild when the rope of the swing she was sitting on snapped. The doctor inserted screws in her leg. However because of her injury, she could not bend her legs properly and so she had to suffer much discomfort. It seemed that this condition had been so for six years. Then she came to the meditation centre and on the twentieth day into her meditation retreat which she had started on the 8th waxing day of Kasone, 1339 BE [May 1977], she could bend her leg and sit as desired; for with the deepening of mindfulness the injury was totally healed. Presently [in the month of Nayone (June)] she is still meditating in the meditation centre.

AW Thein Khyit of 119, 27th Street, Rangoon, fractured her ankle ³⁷ while nursing her grandchild when the rope of the swing she was sitting on snapped. The doctor inserted screws in her leg. However because of her injury, she could not bend her legs properly and so she had to suffer much discomfort. It seemed that this condition had been so for six years. Then she came to the meditation centre and on the twentieth day into her meditation retreat which she had started on the 8th waxing day of Kasone, 1339 BE [May 1977], she could bend her leg and sit as desired; for with the deepening of mindfulness the injury was totally healed. Presently [in the month of Nayone (June)] she is still meditating in the meditation centre.

2. Childhood ‘wind’ ailment cured in two weeks

Sixty-four-year-old Daw Nu of l Hsin Hla Road, Ah Lone Section, Rangoon, had suffered from ‘wind’ since the age of fourteen or fifteen. Often recurring every two or three months, it felt as though the chest and the back were pressing against each other, giving rise to much discomfort. On the 14th waxing day of Hnaung Tagu she arrived at the meditation centre and meditated. About a week later the illness recurred. Her chest was constricted and the belly swelled up so tightly that she thought she was about to fall over. While noting mindfully according to her teacher’s instructions, she expelled phlegm after which she felt at ease. Three or four days later the symptoms reappeared as she was noting. She felt something moving gently within her back. As a result of unrelenting mindfulness, she was completely cured. She persevered in her meditation till she qualified for Nyanzin. Presently she is still around, happy and in good health.

3. Chronic pains of twenty-one years cured in a retreat

Seventy-year-old Daw Hla of 118, 5th Lane, off Sekkawut Road, North Okkalapa, had suffered for twenty-one years from pain in the nape and stinging, pricking numbness that extended from the temple to the eye sockets. She always had to have ointments and medicated oils with her so that she could apply them whenever needed. Eventually one of her eyes was ruined. She had to avoid offensive singeing smells ³⁸ and was carefully selective in her diet. On stooping (or nodding) she would feel stinging pain in the head. On the 1st waning day of Tagu, 1338 BE [April 1976], she came to the meditation centre to meditate. Three days later she felt stinging pains within her nape. Though she noted mindfully they did not go away. However, she persevered according to her teacher’s instructions, and just as a firmly fixed wedge is extracted, the painful sensations vanished. As she continued to meditate, her concentration and insight deepened. While previously she had to see the doctor monthly, now she doesn’t need to; she has done away with all the ointments and medicated oils too. With those ailments completely cured, she is now very happy.

4. Cured of burning constrictions

Sixty-six-year-old Daw Tha of 421 Dhamma Yone Road, Section 16, South Okkalapa, was afflicted with ever-present painful constrictions in the back of the shoulder and back and her breathing was affected. Massage gave only momentary relief. If she sat down quietly for ten to fifteen minutes she would feel burning constrictions within her back as if being jabbed with a burning stick. On the 4th waning day of Kasone, 1339 BE [around May 1977], she came to the meditation centre to meditate. She carefully and mindfully noted rising-falling-sitting-touching-constricting, according to her teacher’s instructions. As a result of such mindfulness the constriction vanished. Two or three days later it recurred, but disappeared again when she noted intently only to appear another time, constricting unbearably. She persisted in noting and it steadily decreased in intensity in stages. Then all at once it completely vanished. Breathing became easy and comfortable. Even now she is still happily meditating.

5. Stiff thigh of five years cured

Sixty-three-year-old Daw Nyan Ein of 108 Anawratha Road, Rangoon, suffered from stiffness of the right thigh for about five years. When she walked the thigh would become taut. When bowing down before the Buddha image, she could not sit properly. She had to sit in a most awkward position, propped on one knee. She needed massage twice or thrice a month, but it did not help much. Though many had urged her to meditate, she had not dared to since she could not even sit properly. Finally on the eve of Thingyan,³⁹ the 10th waning day of Hnaung Tagu, 1338 BE [April 1976], she came to the meditation centre. As a result of serious observant noting according to the teacher’s instructions, a month later she was able to sit normally. Then with continued observant noting, the stiffness in the thigh completely disappeared. She recovered her health and she persevered meditating mindfully until she qualified for Nyanzin. Presently she is still meditating.

6. Cured of asthmatic bronchitis of four years