Mahāsi Sayādaw

Mahāsi Sayādaw

A Discourse on the Wheel of Dhamma

Download the » PDF file (2.09 Mbytes) to print your own booklets.

Contents

Contents

The Practice of Self-mortification

Elaboration of the Eightfold Path

Suffering as the Five Aggregates

Suffering Because of the Five Aggregates

The Truth of the Origin of Suffering

The Truth of the Cessation of Suffering

Knowing the Four Truths Simultaneously

Before the Buddha Claimed Enlightenment

After the Buddha Claimed Enlightenment

Records of the First Buddhist Council

Editor’s Foreword

Editor’s Foreword

As with my other editions of the translated works of the late Venerable Mahāsi Sayādaw, I have removed many of the Pāḷi words or moved them to parentheses for the benefit of those who are not familiar with Pāḷi technical terms. Where Pāḷi passages are explained word by word, using the Nissaya method, a Pāḷi word or phrase is highlighted in blue, followed by its translation in English.

The original translation was published in Rangoon in December 1981, about nineteen years after the Sayādaw gave the Dhamma talks, which spanned a period of several months. To transcribe and translate many hours of tape-recordings is a huge task, but one productive of great merit as it enables a much wider audience to benefit from the late Sayādaw’s profound talks.

This edition aims to extend the audience further still by publishing the book on the Internet. Since my target audience may be less familiar with Buddhism than most Burmese Buddhists, and many may know little about the late Mahāsi Sayādaw, I have added a few footnotes by way of explanation.

References are to the Pāḷi text Roman Script editions of the Pali Text Society — in their translations, these page numbers are given in the headers or in square brackets in the body of the text thus [254]. This practice is also followed by modern translations, like that below:

Thus a reference to M.i.162 would be found on page 162 of volume one in the Pāḷi edition, but on page 254 of Bhikkhu Bodhi’s translation. It would be on a different page in Miss I.B. Horner’s translation, but since the Pāḷi page reference is given, it can still be found. In the Chaṭṭha Saṅgāyana edition of the Pāḷi texts on CD, the references to the pages of the PTS Roman Script edition are shown at the bottom of the screen, and can be located by searching.

I have attempted to standardise the translation of Pāḷi terms to match that in other works by the Sayādaw, but it is impossible to be totally consistent as the various translations and editions are from many different sources. In the index you can find the Pāḷi terms in brackets after the translations, thus the index also serves as a glossary.

The Dhammacakka Sutta, being the Buddha’s First Discourse, is of great significance and importance. However, being given to the five monks who had accompanied the Bodhisatta on his strenuous search for the truth, it is also profound and not easily understood by the average lay person who is still addicted to sensual pleasures, and unfamiliar with meditation practice. The group of five monks had, in fact, been practising meditation even longer than the Bodhisatta. Some Commentaries say that they were the royal astrologers who were present at his birth, others say that they were their sons, but either way they had renounced household life to become ascetics, with firm confidence in the imminent awakening of the Bodhisatta to Buddhahood in the not too distant future.

So, these five ascetics were exceptionally gifted individuals, with many years of prior experience in meditation when they listened to the Buddha’s First Discourse. Nevertheless, only one of them, the Venerable Koṇḍañña, realised the Dhamma and attained nibbāna, thus becoming a Stream-winner at the end of this brief discourse. The other four all had to practise meditation under the personal guidance of the Buddha for one, two, three, and four days respectively, before gaining the Path of Stream-winning. They had to strive very hard too, probably not even pausing to sleep, while the group of six including the Buddha lived on the almsfood brought back by two or three of them.

These days, it is hard to find meditators who are willing to strive hard in meditation. Although I schedule fortnightly one-day retreats, only rarely does anyone attend. These retreats are only twelve hours, so they are, in fact, only half-day retreats — not even a full one-day retreat as practised by the Venerable Vappa to gain the Path.

As the Sayādaw stresses in the last of this series of discourses, in A Matter for Consideration, the realisation of the Dhamma can only come about through actual practice, not merely by listening to discourses (nor by reading books). Yet, some do a great disservice to the Buddha’s practical teaching by discouraging the practice of concentration and insight meditation. I have heard two extreme views: one that listening to discourses is sufficient so there’s no need to practice, and the other that nibbāna cannot be attained in this era, so there’s no point in practising. These very dangerous wrong views should be dismissed, and one should practise meditation earnestly in the expectation of developing the path of insight leading to nibbāna.

Bhikkhu Pesala

September 2021

A Discourse on

A Discourse on

the Wheel of Dhamma

Part One

Delivered on Saturday, 29th September, 1962.¹

Preface to the Discourse

Namo Tassa Bhagavato Arahato Sammāsambuddhassa

Today is the new-moon day of September. Beginning from today, I will expound the the Blessed One’s first discourse, namely the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta — the Great Discourse on the Wheel of Dhamma.

Being the first discourse ever delivered by the Blessed One, it is the most straightforward of his teachings. Rare is the person, among the laity of this Buddhist country of Burma, who has not heard of this discourse. Numerous are those who have committed this Sutta to memory. In almost every town and village, there are religious groups under the name of “The Wheel of Dhamma Reciting Society,” devoted to the recitation of the Sutta and listening to it. Buddhists regard this Sutta with great esteem, and venerate it because it was the first teaching of the Blessed One.

There are numerous Nissaya or other forms of translation, explaining and interpreting the Pāḷi of the Sutta in Burmese. However, there is scarcely any work that explicitly shows what practical methods are available from the Sutta and how they could be utilised by ardent, sincere meditators who aspire to gain the Path and its Fruition. I have expounded this Sutta on numerous occasions, emphasising its practical application to meditation. I formally opened this (Rangoon) Meditation Centre with a discourse of this Sutta and have repeatedly delivered the discourse here. Elsewhere too wherever a new meditation centre was opened, I always employed this Sutta as an inaugural discourse.

The Buddhist Canon has three main divisions — the three baskets or Tipiṭaka in Pāḷi. These are the Sutta Piṭaka — the collection of discourses, the Vinaya Piṭaka — the rules of discipline, and the Abhidhamma Piṭaka — the Analytical teachings. The Discourse on the Wheel of Dhamma is included in the Sutta Piṭaka, which consists of five sections (nikāya): the Dīghanikāya, the Majjhimanikāya, the Saṃyuttanikāya, the Aṅguttaranikāya, and the Khuddakanikāya. The Saṃyuttanikāya is divided into five groups (vagga): a) Sagāthāvagga, b) Nidānavagga, c) Khandhavagga, d) Saḷāyatanavagga, and e) Mahāvagga. The Mahāvagga is divided into twelve chapters such as the Maggasaṃyutta, the Bojjhaṅgasaṃyutta, the Satipaṭṭhānasaṃyutta, the last of which is the Saccāsaṃyutta. The Wheel of Dhamma appears as the first discourse in the second group of the Saccāsaṃyutta and was recited as such in the proceedings of the Sixth Buddhist Council (Saṅgāyana). In the Sixth Buddhist Council edition of the Tipiṭaka, it is recorded on pages 368-371 of the third volume of the Saṃyutta Piṭaka.² There, the introduction to the Discourse reads: “Evaṃ me sutaṃ, ekaṃ samayaṃ… Thus have I heard. At one time…” These were the introductory words uttered by the Venerable Ānanda when interrogated by the Venerable Mahākassapa at the First Buddhist Council held just over three months after the passing away of the Blessed One. The Venerable Mahākassapa said to the Venerable Ānanda:–

“Friend Ānanda, where was the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta delivered? By whom was it delivered and on whose account? And how was it delivered?” The Venerable Ānanda answered, “Venerable Mahākassapa, thus have I heard:–

“At one time the Blessed One was staying at the Sage’s Resort, the Pleasance of Isipatana, (where Pacceka Buddhas and Enlightened Ones alighted from the sky), in the Deer Sanctuary, in the township of Benares. Then the Blessed One addressed the group of five monks. ‘These two extremes, monks, should not be followed by one who has gone forth from the worldly life.’

The Date of the Discourse

The Date of the Discourse

This introduction lacks a definite date of delivery of the discourse. As in all other Suttas, the date was mentioned merely as “At one time.” Precise chronological data as to the year, month, and day on which each discourse was delivered would have been very helpful. However, chronological details may have been an encumbrance to committing the Suttas to memory, and to their recitation. Thus it is not easy to place a precise date for each the Suttas. It should, however, be possible to work out the exact date on which the Dhammacakka Sutta was delivered because it was the first discourse of the Blessed One, and also because reference could be made to internal evidence provided in other Suttas and the Vinaya Piṭaka.

The Buddha attained Supreme Enlightenment on the night of the full-moon of May in the year 103 of the Great Era. Then he taught this Dhammacakka Sutta in the early evening of the full-moon day of the following July. It is exactly 2,506 years now in this year 1324 of the Burmese Era since the Buddha’s final parinibbāna took place. Adding on the 45 years of the dispensation before the parinibbāna, it would total 2,551 years. Thus it was on the first watch of the full-moon of July, 2,551 years ago that this first discourse was delivered by the Blessed One. Western scholars regard this estimation as 60 years too early. According to their calculation, it was only 2,491 years ago that the first discourse was taught. As the event of the Turning of the Wheel of Dhamma took place in the East, I would prefer to go by the oriental calculation and regard the first discourse as being taught 2,551 years ago.³

The deer park, in which deer were given sanctuary, must have been a forested area with deer roaming about freely. At present, however, the area has been depleted of forest trees and has become an open plain with cultivated patches surrounding human habitations. In ancient times, Paccekabuddhas travelled through the sky by supernormal powers from the Gandhamādana mountain and descended to earth at this isolated place. Likewise, the Enlightened Ones of the distant past came here by psychic powers and alighted on this same spot to teach their first discourse. Hence the name, “The Sage’s Resort.”

The introduction to the Sutta says that the Blessed One taught the first discourse to the group of five monks while he was staying in the pleasance of the deer sanctuary in the township of Benares. That is all the information that could be obtained from the introductory statement, which is bare and inadequate. It needs some elaboration, which I propose to provide by drawing on material from other Suttas.

Three Kinds of Introduction

The introduction to a Sutta explains on whose account it was taught by the Buddha. Introductions are of three kinds.

1) An introduction that gives a background story of the remote past. This provides an account of how the Bodhisatta, the future Buddha, fulfilled the perfections required of an aspirant Buddha, beginning from the time of prophecy proclaimed by Dīpaṅkara Buddha to the time when he was reborn in the Tusita heaven as a king of the deities named Setaketu. There is no need, nor enough time, to deal more with this background story of the distant past.

2) An introduction touching on the background story of the intermediate period. This deals with the account of what passed from the time of existence in the Tusita heaven to the attainment of Full Enlightenment on the Throne of Wisdom. I will give attention to this introduction to a considerable extent.

3) An introduction that tells of the recent past, just preceding the teaching of the Dhammacakka Sutta. This is what is learnt from the statement, “Thus have I heard. At one time…” quoted above. I will deal now with relevant extracts from the second category of introductions, drawing material from the Sukhumāla Sutta ⁴ of the Tikanipāta, Aṅguttaranikāya; the Pāsarāsi or Ariyapariyesanā Sutta,⁵ and Mahāsaccaka Sutta ⁶ of the Mūlapaṇṇāsa, Majjhimanikāya; Bodhirājakumāra Sutta ⁷ and Saṅgārava Sutta ⁸ of Majjhimapaṇṇāsa, Majjhimanikāya; Pabbajjā Sutta,⁹ Padhāna Sutta ¹⁰ of the Suttanipāta, and many other Suttas.

The Bodhisatta and Worldly Pleasures

After the Bodhisatta had passed away from the Tusita heaven, he entered the womb of Mahāmāyā Devī, the Principle Queen of King Suddhodana of Kapilavatthu. The Bodhisatta was born on Friday, the full-moon day of May in the year 68 of the Great Era, in the pleasure-grove of Sal trees called the Lumbinī Grove and was named Siddhattha. At the age of sixteen, he was married to Yasodharā Devī daughter of Suppabuddha, the Royal Master of Devadaha. Thereafter, surrounded by forty thousand attendant princesses, he lived in enjoyment of royal pleasures in great magnificence. While he was thus wholly given over to sensual pleasure amidst pomp and splendour, he came out one day accompanied by attendants to the royal pleasure-grove for a garden feast and merry-making. On the way to the grove, the sight of a decrepit, aged person gave him a shock and he turned back to his palace. As he went out on a second occasion he saw a person who was sick with disease and returned greatly alarmed. When he sallied forth for the third time, he was agitated in heart on seeing a dead man and hurriedly retraced his steps. The agitation that set upon the Bodhisatta are described in the Ariyapariyesanā Sutta.

The Ignoble Search

The Bodhisatta pondered thus; “When oneself is subject to aging to seek and crave for what is subject to aging is not befitting. What are subject to aging? Wife and children, slaves, goats and sheep, fowl and pigs, elephants, horses, cattle, gold and silver, all objects of pleasures and luxuries animate and inanimate are subject to aging. Being oneself subject to aging, to crave for these objects of pleasures, to be enveloped and immersed in them is improper.”

“Similarly, it does not befit one, when oneself is subject to disease and death, to crave for sensual objects that are subject to disease and death. To go after what is subject to aging, disease, and death is improper, and constitutes an ignoble search (anariyāpariyesanā).”

The Noble Search

“Being oneself subject to aging, disease, and death, to go in search of that which is not subject to aging, disease, and death constitutes a noble search (ariyāpariyesanā).”

That the Bodhisatta himself was engaged at first in the ignoble search was described in the Sutta as follows:-

“Now bhikkhus, before my Enlightenment while I was only an unenlightened Bodhisatta, being myself subject to birth I sought after what was also subject to birth; being myself subject to aging I sought after what was also subject to aging.”

This was a denunciation of the life of pleasure he had lived with Yasodharā amidst the happy society of attendant princesses. Then, having perceived the wretchedness of such a life, he resolved to go in search of the peace of nibbāna, which is free from birth, aging, disease, and death. he said, “Having perceived the wretchedness of being myself subject to birth, aging, it occurred to me it would be fitting if I were to seek the incomparable, unsurpassed peace of nibbāna, free from birth and aging.”

Thus it occurred to the Bodhisatta to go in search of the peace of nibbāna, which is free from aging, disease, and death. That was a very laudable aim and I will consider it further to see clearly how it was so. Suppose there was someone who was already old and decrepit. Would it be wise for him to seek the company of another man or woman who, like himself, was aged and frail; or of someone who though not advanced in age yet would surely be old in no time? No, it would not be wise at all. Again, for someone who was himself in declining health and suffering, it would be quite irrational if he were to seek the companionship of another who was afflicted with a crippling disease. Companionship with someone who though, enjoying good health presently, would soon be troubled with illness, would not be prudent either. There are those who, hoping to enjoy each other’s company for life, got married and settled down. Unfortunately, one of the partners soon becomes a bed-ridden invalid, imposing on the other the onerous duty of looking after their stricken mate. The hope of a happy married life may be dashed when one of the partners passes away leaving only sorrow and lamentation for the bereaved. Ultimately both of the couples would be faced with the misery of aging, disease, and death.

Thus it is extremely unwise to pursue sensual pleasures, which are subject to aging, disease, and death. The most noble search is to seek out what is not subject to aging, disease, and death. Here at this meditation centre, it is gratifying that the devotees, monks, and laymen, are all engaged in the noble search for the unaging, the unailing, and the deathless.

On his fourth excursion to the pleasure grove, the Bodhisatta met a monk. On learning from the monk that he had gone forth from the worldly life and was engaged in spiritual endeavour, it occurred to the Bodhisatta to renounce the world, become a recluse and go in search of what is not subject to aging, disease, and death. When he had gained what he had set out for, his intention was to pass on the knowledge to the world so that others would also learn to be free from misery of being subject to aging, disease, and death. A noble thought indeed, a noble intention indeed!

On that same day, about the same time, a son was born to his consort Yasodharā Devī. When he heard the news, the Bodhisatta murmured, “An impediment (Rāhula) has arisen, a fetter has been born.” On learning this remark of the Bodhisatta, his father King Suddhodana had his newborn grandson named as “Rāhula” (Prince Impediment), hoping that the child would prove to be an impediment to the Bodhisatta and hinder his plan of renunciation.

However, the Bodhisatta had become averse to the pleasures of the world. That night be remained disinterested in the amusements provided by the entertainers and fell into an early slumber. The discouraged musicians lay down their instruments and went to sleep there and then. The sight of recumbent, sleeping dancers that met him on awakening in the middle of the night, repulsed him and made the magnificent apartment seem like a cemetery full of corpses.

Thus at midnight the Bodhisatta went forth on the Great Renunciation riding the royal horse Kanthaka and accompanied by his groom Channa. When they came to the river Anomā, he cut off his hair and beard while standing on the sandy beach. Then after discarding the royal garments, he put on the yellow robes offered by the brahmā god Ghaṭikāra and became a monk. The Bodhisatta was only twenty-nine then, an age most favourable for the pursuit of pleasures. That he renounced with indifference the pomp and splendour of a sovereign and abandoned the solace and comfort of his consort Yasodharā and retinue at such a favourable age, while still blessed with youth, is really awe-inspiring.

Approaching the Sage Āḷāra

At that time the Bodhisatta was not yet in possession of practical knowledge of leading a holy life. So he made his way to the famous ascetic Āḷāra. He was no ordinary person; of the eight stages of mundane jhānic attainments, he had personally mastered seven stages up to the absorption dwelling on nothingness (ākiñcaññāyatana jhāna) and was imparting this knowledge to his pupils.

Before the appearance of the Buddha, such teachers who had achieved jhānic attainments served as trustworthy masters giving practical instructions on the method to attain jhāna. Āḷāra was famous like a Buddha in those times. The Theravāda literature is silent about him, but in the Lalitavistara, a biographical text of the northern School of Buddhism, it was recorded that the great teacher had lived in the state of Vesāli and that he had three hundred pupils learning his doctrine.

Taking Instructions from Āḷāra

How the Bodhisatta took instructions from the sage Āḷāra is described thus: “Having gone forth and become a recluse in pursuit of what is holy and good, seeking the supreme, incomparable peace of nibbāna, I drew to where Āḷāra Kālāma was and addressed him thus: ‘Friend Kālāma, I wish to lead the holy life under your doctrine and discipline.’ When I had thus addressed him Āḷāra replied. ‘Friend Gotama is welcome. Of such a nature is this doctrine that in a short time, an intelligent man can realise for himself and abide in what his teacher has realised as his own.” After these words of encouragement, Āḷāra gave him practical instructions on the method.

Reassuring Words

Āḷāra’s statement that his doctrine, if practised as taught, could be realised soon by oneself was very reassuring, and inspired confidence. A pragmatic doctrine is trustworthy and convincing only if it could be realised by oneself, and in a short time. The sooner the realisation is possible, the more heartening it will be. The Bodhisatta was thus satisfied with Āḷāra’s words, and this thought arose in him. “It is not by mere faith that Āḷāra announces that he has learned the Dhamma, Āḷāra has surely realised the Dhamma himself, he knows and understands it.”

That was true. Āḷāra did not cite any texts as authority. He did not say that he had heard it from others. He clearly stated that he had realised himself what he knew personally. A meditation teacher must be able to declare his conviction boldly like him. Without having practised the Dhamma personally, without having experienced and realised it in a personal way, to claim to be a teacher in mediation, to teach and write books about it, after just learning from the texts on meditation methods, is most incongruous and improper. It is like a physician prescribing medicine not yet clinically tested and tried by him, and which he dare not administer on himself. Such teachings and publications are surely undependable and uninspiring. However, Āḷāra taught boldly what he had realised himself. The Bodhisatta was fully impressed by him, and the thought arose in him. “Not only Āḷāra has faith, I also have faith; not only Āḷāra has energy, mindfulness, concentration, wisdom, I also have them.” Then he strove for the realisation of that Dhamma that Āḷāra declared he had learned and realised for himself. In no time he learned the Dhamma that led him as far as the jhānic stage of nothingness.

He then approached Āḷāra Kālāma and asked him whether the realm of nothingness, which he had claimed to have realised himself and live in possession of, was the same stage that the Bodhisatta had now reached. Āḷāra replied, “This is as far as my teaching leads, which I have declared to have realised and abide in the possession of it, the same stage as friend Gotama has reached.” Then he uttered these words of praise. “Friend Gotama is a supremely distinguished person. The realm of nothingness is not easily attainable. Yet you have realised it in no time. It is truly wonderful. Fortunate we are that we should meet such a distinguished ascetic as your reverence. As I have realised the Dhamma, so you have realised it too. As you have learnt it, so I have learnt to the same extent as you. Friend Gotama is my equal in Dhamma. We have a large community here. Come, friend, let us together direct this company of disciples.”

Thus Āḷāra, the teacher, set up the Bodhisatta, his pupil as a complete equal to himself and honoured the Bodhisatta by delegating to him the task of guiding one hundred and fifty pupils, which was exactly half of the disciples under his instruction.

However, the Bodhisatta stayed there only for a short time. While staying there, this thought occurred to him, “This doctrine does not lead to aversion, to the abatement and cessation of passion, to quiescence for higher knowledge and full enlightenment nor to nibbāna, the end of suffering, but only as far as the attainment of the realm of nothingness. Once there, a long life of 60,000 world cycles follows and after expiring from there, one reappears in sensual realms, and undergoes suffering again. It is not the doctrine of the undying that I seek.” Thus becoming indifferent to the practice that led only to the jhānic realm of nothingness he abandoned it and departed from Āḷāra’s meditation centre.

Approaching the Sage Udaka

After leaving that place, the Bodhisatta was on his own for some time, pursuing the supreme path of tranquillity to reach the deathless nibbāna. Then the fame of Udaka Rāmaputta, (the son of Rāma, the disciple of the sage Rāma) reached him. He came to where Udaka was and sought to lead the religious life under the dhamma and discipline of the sage Rāma. His experiences under the guidance of Udaka, how Udaka explained the dhamma, how the Bodhisatta was impressed with that doctrine, and practised it, how he realised the dhamma and recounted to Udaka what he had gained, is described in almost exactly the same words as before.

We have, however, to note carefully that Udaka Rāmaputta, as his name implied, was a son of Rāma or a disciple of Rāma. The sage Rāma was accomplished to go through all the eight stages of jhāna and reached the highest jhānic realm of neither perception nor non-perception. However, when the Bodhisatta reached where Udaka was, the old sage Rāma was no more. Therefore in asking Udaka about Rāma’s attainments, he used the past tense pavedesi. “How far does this doctrine lead concerning which Rāma declared that he had realised it for himself and entered upon it?”

Then there is the account of how this thought occurred to the Bodhisatta: “It is not only Rāma who had faith, industry, mindfulness, concentration, and wisdom. I also have them.” There is also this passage where it was stated that Udaka set him up as a teacher. “You know this doctrine and Rāma knew this doctrine. You are the same as Rāma and Rāma was the same as you. Come, friend Gotama, lead this following and be their teacher.” Again the passage where the Bodhisatta recounted “Udaka, the disciple of Rāma, although my companion in the holy-life, set me up as his teacher.”

These textual references make it clear that the Bodhisatta did not meet the sage Rāma, but only with Rāma’s disciple, Udaka who explained to him the doctrine practised by Rāma. The Bodhisatta followed the method as described by Udaka and was able to realise the stage of neither perception nor non-perception. Having learnt the doctrine himself and realised and entered upon the realm of neither perception nor non-perception like the sage Rāma, he was invited by Udaka to accept the leadership of the company.

Where Udaka resided and how big his following was, is not mentioned in the Theravāda literature. However, the Lalitavistara, the biography of the Buddha of Northern Buddhism, states that Udaka’s centre was in the district of Rājagaha and that he had a company seven hundred strong. It is to be noted that at the time of meeting the Bodhisatta, Udaka himself had not yet attained the jhāna of neither perception nor non-perception. He explained to the Bodhisatta only what Rāma had achieved. So when the Bodhisatta proved himself to be the equal of his master by realising the stage of neither perception nor non-perception, he offered the Bodhisatta the leadership of the whole company. According to the Subcommentary (Ṭīkā) he later strove hard, emulating the example set by the Bodhisatta, and finally attained the highest jhānic stage of neither perception nor non-perception.

The Bodhisatta remained as a leader of the company at the centre only for a short time. It soon occurred to him, “This doctrine does not lead to aversion, to absence of passion nor to quiescence for gaining knowledge, supreme wisdom, and nibbāna, but only as far as the realm of neither perception nor non-perception. Once there, a long life of 84,000 world cycles is enjoyed only to come back again to the sensual realm, and be subject to much suffering. This is not the doctrine of the deathless that I seek.” Then becoming indifferent to the doctrine, which leads only to the realm of neither perception nor non-perception, he gave it up and departed from Udaka’s centre.

Extreme Austerities in the Uruvela Forest

After he left the centre, the Bodhisatta wandered about the land of Māgadha, searching on his own the peerless path of tranquillity, the deathless nibbāna. During his wanderings he came to the forest of Uruvela near the large village of Senānigama. In the forest he saw clear water flowing in the river Nerañjarā. Perceiving a delightful spot, a serene dense grove, a clear flowing stream with a village nearby, which would serve as an alms resort, it occurred to him: “Truly this is a suitable place for one intent on striving,” and he stayed on in the forest.

At that time the Bodhisatta had not yet worked out a precise system of right struggle. austere practices were, of course, widely known and in vogue throughout India at that time. Concerning these practices three similes came to the mind of the Bodhisatta.

A log of sappy wood freshly cut from a sycamore tree and soaked in water cannot produce fire by being rubbed with a similar piece of wet sappy wood or with a piece of some other wood. Just so, while still entangled with objects of sensual desires such as wife and family, while delighting in passionate pleasures and lustful desires are not yet silenced within, however strenuously someone strives, he is incapable of wisdom, insight, and incomparable full awakening. This was the first simile that occurred to the Bodhisatta.

Even if the sycamore log is not soaked in water, but is still green and sappy being freshly from the tree it will also not produce any fire by friction. Just so, even if he has abandoned the objects of sensual desires such as wife and family and they are no longer near him, if he still delights in thoughts of passionate pleasures, and lustful desires still arise in him, he is incapable of wisdom, insight, or full awakening. This is the second simile.

According to the Commentary this simile has a reference to the practices of the Brahmadhammika ascetics. Those Brahmins led a holy ascetic life from youth to the age of forty eight when they went back to married life in order to preserve the continuity of their clan. Thus while they were practising the holy life, they would have been tainted with lustful thoughts.

The third simile concerns a dry sapless log not soaked in water. A log of dry wood will kindle fire when rubbed against another. Similarly, having abandoned objects of sensual desires and weaned himself of lustful thoughts and cravings, he is capable of attaining wisdom, insight, and full awakening, whether he practises extreme austerity or whether he strives painlessly without torturing himself.

Extreme Austerity of Crushing the Mind

Of the two methods open to him according to the third simile, the Bodhisatta considered following the path of austerity, “What if, with my teeth clenched and my tongue cleaving the palate, I should press down, constrain, and crush the naturally arising thoughts with my mind.”

The Pāḷi text quoted here corresponds with the text in the Vitakkasaṇṭhāna Sutta.¹¹ However, the method of crushing the thought with the mind as described in the Vitakkasaṇṭhāna Sutta was one prescribed by the Buddha after attaining Enlightenment. As such, it involves banishment of a lustful thought that arises of its own accord by noting its appearance as an exercise of insight meditation in accordance with the Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta and other similar texts. The method of crushing the thought with the mind as described here refers to the practical exercises performed by the Bodhisatta before he attained the knowledge of the Middle Path and is, therefore, at odds with the Satipaṭṭhāna method.

However, the Commentary’s interpretation implies suppression of evil thoughts with moral thoughts. If this interpretation is correct, this method, being in accord with the Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta and other texts, would have resulted in Enlightenment for the Bodhisatta. Actually, this method led him only to extreme suffering and not to Buddhahood. Other austere practices taken up afterwards also merely led the Bodhisatta into wrong paths.

The austere practices followed by the Bodhisatta at that time appear to be somewhat like that of mind annihilation being practised nowadays by followers of a certain school of Buddhism. During our missionary travels in Japan, we visited a large temple where a number of people were engaged in meditation exercises. Their meditation method consists of blotting out the thought whenever it arises. Thus emptied of mental activity, the end of the road is reached, namely, nothingness. The procedure is as follows:-

Young Mahāyāna monks sat cross-legged in a row, about six in number. The abbot went round showing them the stick with which he would beat them. After a while he proceeded to administer one blow on the back of each meditator. It was explained that while being beaten it was possible that mind disappeared altogether resulting in nothingness. Truly a strange doctrine. This is, in fact, annihilation of thought by crushing it with mind, presumably the same technique employed by the Bodhisatta to crush the thought with the mind by clenching the teeth. The effort proved very painful for him and sweat oozed from his armpits, but no superior knowledge was attained.

Absorption Restraining the Breath

Then it occurred to the Bodhisatta, “What if I control respiration and concentrate on the breathless jhāna.” With that thought, he restrained the in and out breaths through the mouth and nose. With the holding of respiration by the mouth and nose, there was a roar in the ears due to the rushing out of the air just like the bellows of a forge making a roaring noise. There was intense bodily suffering, but the Bodhisatta was relentless. He held his breath, not only of the mouth and nose, but also of the ears. As a result, violent winds rushed up to the crown of the head, causing pains as if a strong man had split open the head with a mallet, as if a powerful man were tightening a rough leather strap around the head. Violent winds pushed around in the belly causing pain like being cut by a sharp butcher’s knife. There was intense burning in the belly as if roasted over a pit of live coals. The Bodhisatta overcome physically by pain and suffering, fell down in exhaustion and lay still. When the deities saw him lying prone, they said, “The monk Gotama is dead.” Other deities said, “The monk Gotama is neither dead nor dying. He is just lying still, dwelling in the state of Arahantship.” In spite of all these painful efforts no higher knowledge was gained.

Extreme Austerity of Fasting

So it occurred to him, “What if I strive still harder entirely abstaining from food.” Knowing his thoughts, the deities said, “Please, dear Gotama, do not entirely abstain from food, if you do so, we will infuse heavenly nourishment through the pores of your skin. You can live on that.” Then it occurred to the Bodhisatta, “If I claim to be fasting completely, but these deities should thus sustain me, that would be for me a lie,” thus the Bodhisatta rejected the deities’ offer, saying that he refused to be infused with divine nourishment.

So it occurred to him, “What if I strive still harder entirely abstaining from food.” Knowing his thoughts, the deities said, “Please, dear Gotama, do not entirely abstain from food, if you do so, we will infuse heavenly nourishment through the pores of your skin. You can live on that.” Then it occurred to the Bodhisatta, “If I claim to be fasting completely, but these deities should thus sustain me, that would be for me a lie,” thus the Bodhisatta rejected the deities’ offer, saying that he refused to be infused with divine nourishment.

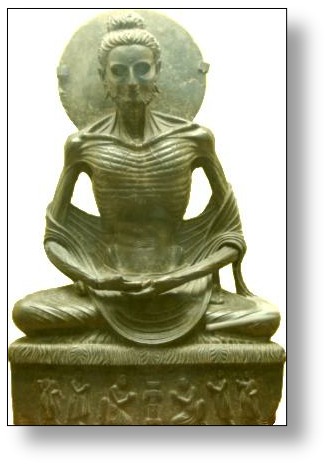

Then he decided to take less and less nourishment, only as much bean soup as will fit the hollow of one hand. Living, thus, on about five or six spoonfuls of bean soup each day, the body reached a state of extreme emaciation. The limbs withered, only skin, sinews, and bones remained. The vertebrae protruded. The widely separated bones jutted out, presenting an ungainly, ghastly appearance just as in images of the Bodhisatta undergoing extreme austerity.¹² The eyes, shrunk down in their sockets, looked like the reflection from water sunk deep in a well. The scalp had shrivelled up like a gourd withered in the sun. The emaciation was so extreme that if he attempted to feel the belly skin, he touched the spine; if he felt for the spine, he touched the belly skin. When he attempted to evacuate the bowels or make water, the effort was so painful that he fell forward on his face, so weakened was he through this extremely scanty diet.

Seeing this extremely emaciated body of the Bodhisatta, people said, “The monk Gotama is black.” Others said, “The monk Gotama is dark brown.” Others said, “The monk Gotama has the brown blue colour of a torpedo fish.“ So much had the clear, bright, golden colour of his skin deteriorated.

Māra’s Persuasion

While the Bodhisatta strove hard and practised extreme austerity to subdue himself, Māra came and addressed the Bodhisatta persuasively in beguiling words of pity. “Friend Gotama, you have gone very thin and assumed an ungainly appearance. You are now in the presence of death. There is only one chance in a thousand for you to live. Friend Gotama! Try to remain alive. Life is better than death. If you live, you can do good deeds and gain merits.”

The meritorious deeds mentioned here by Māra have no reference whatsoever to the merits accruing from acts of charity and observance of precepts, practices which lead to the path of liberation; nor to merits that result from the development of insight and the attainment of the Path.

Māra knew only about merits gained by leading a holy life, abstaining from sexual intercourse and worshipping holy fires. These practices were believed in those times to lead to a noble, prosperous life in future existences. However, the Bodhisatta was not enamoured with the blessings of existences, so he replied to Māra, “I do not need even an iota of the merits of which you speak. Go and talk of merit to those who need it.”

A misconception has arisen concerning this utterance of the Bodhisatta that he was not in need of any merits. It is that “meritorious deeds are to be abandoned, not to be sought for nor carried out by one seeking release from the cycle of existences like the Bodhisatta.” A person once approached me and sought elucidation on this point. I explained to him that when Māra was talking about merit, he did not have in mind the merits accrued from acts of charity, observance of precepts, the development of insight through meditation or attainment of the Path. He could not know of them. Nor was the Bodhisatta in possession then of precise knowledge of these meritorious practices; only that the Bodhisatta was then engaged in austerities, taking them to be noble. Thus when Bodhisatta said to Māra, “I do not need any merit,” he was not referring to the meritorious practices that lead to nibbāna, but only to such deeds as were then believed to assure pleasurable existences. The Commentary supports this view. It states that in saying, “I do not need any merit,” the Bodhisatta meant only the merit of which Māra spoke, namely, acts of merit that are productive of future existences. It can thus be concluded that no question arises of abandonment of meritorious practices that will lead to nibbāna.

At that time the Bodhisatta was still working under the delusion that austere practices were the means of attaining higher knowledge. Thus he said, “This wind that blows can dry up the waters of the river. So while I strive strenuously why should it not dry up my blood? When the blood dries up, bile and phlegm will run dry. As the flesh gets wasted too, my mind will become clearer — mindfulness, concentration, and wisdom will be more firmly established.”

Māra was also under the wrong impression that abstention from food would lead to liberation and higher knowledge. It was this anxiety that motivated him to coax the Bodhisatta away from following the path of starvation. With the same wrong notion, the group of five ascetics waited upon him, attending to all his needs, hoping that this abstemious practices would lead to Buddhahood and intending to be the first recipients of his teaching on liberation. It is clear therefore that it was a universal belief in those days that extreme self-mortification was the right path to Enlightenment.

Right Reasoning

After leading the life of extreme self-mortification for six years without any beneficial results, the Bodhisatta began to reason thus: “Whatever ascetics or brahmins in the past had felt painful, racking, piercing feeling through practising self-mortification, it may equal this suffering, but not exceed it. Whatever ascetics or brahmins in the future will feel painful, racking, piercing feeling though the practice of self-mortification, it may equal this suffering, but not exceed it; whatever ascetics or brahmins in the present feel painful, racking, piercing feelings through the practice of self-mortification it may equal this suffering, but not exceed it. However, by this gruelling asceticism I have not attained any distinction higher than ordinary human achievements. I have not gained the Noble One’s knowledge and vision, which could uproot the defilements. Might there be another way to Enlightenment apart from this path of self-mortification?

Then the Bodhisatta thought of the time when, as an infant, he sat alone under the shade of a rose-apple tree, entering and absorbed in the first jhānic stage of meditation, while his father King Suddhodana was engaged in the ceremonial ploughing of the nearby fields. He wondered whether this method might be the right way to truth!

Absorption While an Infant

The Bodhisatta was born on the full moon of May. It appeared that the royal ploughing ceremony was held sometime in June or July a month or two later. The infant child was laid down on a couch of magnificent cloths, under the shade of a rose-apple tree. An enclosure was then formed by setting up curtains around the temporary nursery, with royal attendants respectfully watching over the royal infant. As the royal ploughing ceremony progressed in magnificent pomp and splendour, with the king himself partaking in the festivities, the royal attendants were drawn to the splendid scene of activities going on in the nearby fields. Thinking that the royal baby had fallen asleep, they left him lying secure in the enclosure and went to enjoy the ceremony. The infant Bodhisatta, on looking around and not seeing any attendant, sat up from the couch and remained seated with his legs crossed. By virtue of habit-forming practices throughout many life-times, he instinctively started contemplating the incoming and outgoing breathes. He was soon established in the first absorption, which is characterised by five factors: initial application, sustained application, joy, bliss, and one-pointedness.

The attendants had been gone for some time, lost in the festivities. When they returned, the shadows of the trees had moved with the passage of time. However, the shade of the rose-apple tree under which the infant was left lying was found to have remained steadfast without shifting. They saw the infant Bodhisatta sitting motionless on the couch. King Suddhodana, when informed, was struck by the spectacle of the unmoving shadow and the still, sitting posture of the child and in great awe, he made obeisance to his son.

The Bodhisatta recalled the experience of absorption in breathing meditation he had gained in childhood, and thought, “Might that be the way to the truth?” Following up that memory, there came the realisation that method was the right way to Enlightenment.

The jhānic experiences were so pleasurable that the Bodhisatta thought to himself. “Am I afraid of the pleasures of jhāna?” Then he thought: “No, I am not afraid of such pleasures.”

Resumption of Normal Meals

Then it occurred to the Bodhisatta: “It is not possible to attain absorption with a body so emaciated. What if I take some solid food, like I used to take. Thus physically nourished and strengthened, I will be able to work to attain the absorptions.” Seeing him partaking of solid food, the group of five ascetics misunderstood his actions. They were formerly royal astrologers who had predicted, at the time of his birth, that he would become a Fully Enlightened Buddha.

There were eight royal astrologers at his birth. When asked to predict what the future held for the royal infant, three of them raised two fingers each and made pronouncements that the infant would grow up to be a Universal Monarch or an Omniscient Buddha. The remaining five raised only one finger each to give a single interpretation that the child would undoubtedly become a Buddha.

According to the Pāsarāsi Sutta Commentary,¹³ these five court astrologers forsook the world before they got enchained to the household life and took to the forest to lead a holy life. However, the Buddhavaṃsa Commentary and some other texts stated that seven astrologers raised two fingers each giving double interpretations while the youngest Brahmin, who would in time become the Venerable Koṇḍañña, raised only one finger and made the definite prediction that the child was a future Buddha.

This young Brahmin together with the sons of four other Brahmins had gone forth from the world and banded together to form the group of five ascetics, who were awaiting the Great Renunciation of the Bodhisatta. When news reached them that the Bodhisatta was practising extreme austerities in the Uruvela forest, they journeyed there and became his attendants, hoping that when he achieved Enlightenment, he will share his knowledge with them, and they would be the first to hear the message.

When the five ascetics saw the Bodhisatta partaking of solid food, they were disappointed. They thought, “If living on a handful of pea soup has not led him to higher knowledge, how could he expect to attain that by eating solid food again?” They misjudged that he had abandoned the struggle and reverted to the luxurious way of life to gain riches and personal glory. Thus they left him in disgust and went to stay in the deer sanctuary in the township of Benares.

The Enlightenment

The Enlightenment

The departure of the five ascetics afforded the Bodhisatta the opportunity to struggle for final liberation in complete solitude. The Commentary on the Mahāsaccaka Sutta¹⁴ gives a description of how, working alone with no one near him, for a full fortnight, seated on the throne of wisdom, under the tree of Enlightenment, he attained Omniscience, the Enlightenment of a Buddha.

The Bodhisatta had gone forth at the age of twenty-nine and spent six years practising extreme austerity. Now at the age of thirty-five, still youthful and in good health, within fifteen days of resuming regular meals, his body recovered its former strength, and he regained the thirty-two physical characteristics of a great man. Having thus regained his strength through normal nourishment, the Bodhisatta practised the in-breathing and out-breathing meditation, and remained absorbed in the bliss of the first jhāna, which was characterised by initial application, sustained application, joy, bliss, and one-pointedness. Then he entered the second jhāna, which was accompanied by joy, bliss, and one-pointedness. At the third stage of jhāna, he enjoyed only bliss and one-pointedness, and at the fourth stage, only equanimity and one-pointedness.

Early on the full moon day of May in the year 103 of the Great Era i.e. 2,551 years ago counting back from 1962, he sat down under the Bodhi Tree near the market town of Senānigama awaiting the hour of going for alms. At that time, Sujātā, the daughter of a rich man from the village, was making preparations to give an offering to the tree-spirit of the Bodhi tree. She sent her maid ahead to tidy up the area under the spread of the sacred tree. At the sight of the Bodhisatta seated under the tree, the maid thought that the deity had made himself visible to receive their offering in person. She ran back in great excitement to inform her mistress. Sujātā put the milk-rice that she had cooked early in the morning in a golden bowl worth a hundred thousand pieces of money, covering the same with another golden bowl. She then proceeded with the bowls to the foot of the Banyan tree where the Bodhisatta remained seated and put the bowls into the hands of the Bodhisatta saying, “May your wish succeed as mine has.” So saying she departed.

Sujātā, on becoming a maiden, had made a prayer at the banyan tree; “If I get a husband of equal status with myself and if my first born is a son, I will make an offering.” Her prayer had been fulfilled and her offering of milk-rice that day was intended for the tree deity in fulfilment of her promise. However, later when she learnt that the Bodhisatta had gained Enlightenment after taking the milk-rice offered by her, she was overjoyed with the thought that she had done a noble deed of the greatest merit.

The Bodhisatta then went down to the river Nerañjarā to bathe. After bathing, he formed the milk-rice offered by Sujātā into forty-nine morsels and ate it. The meal over, he discarded the golden bowl in the river saying, “If I am to become a Buddha today, let the bowl go upstream.” The bowl drifted upstream for a considerable distance against the swift flowing current, and on reaching the abode of the nāga-king Kāla, sank into the river below the bowls of the three previous Buddhas (tiṇṇaṃ buddhānaṃ thālāni ukkhipitvā aṭṭhāsi).

The Bodhisatta rested the whole day in the forest glade near the bank of the river. As evening fell, he went towards the Bodhi tree, meeting on the way a grass-cutter named Sottiya who gave him eight handfuls of grass. In India, holy men used to prepare a place to sit and sleep on by spreading sheaves of grass. The Bodhisatta spread the grass under the tree on the eastern side. Then with the solemn resolution, “I will not stir from this seat until I have attained supreme wisdom,” he sat down cross-legged, facing east.

At this point Māra appeared and contested for the seat under the Bodhi tree with a view to oppose his resolution and prevent him from attaining Buddhahood. By invoking the virtues he had accumulated through ages, fulfilling the ten perfections such as charity, he overcame the obstruction made by Māra before the sun had set. After thus vanquishing Māra, the Bodhisatta acquired through jhāna, in the first watch of the night, the knowledge of previous existences; in the middle watch of the night, the divine eye; and in the last watch of the night he contemplated the law of Dependent Origination followed by the development of insight into the arising and ceasing of the five aggregates of attachment. This insight gave him in succession the knowledge pertaining to the four Paths, finally resulting in full Enlightenment or Omniscience.

Having become a Fully Enlightened One, he spent seven days on the throne of wisdom under the Bodhi tree and seven days each at six other places, forty-nine days in all, enjoying the bliss of the Arahantship and pondering his newly discovered Dhamma.

Extreme Austerity Is a Form of Self-mortification

The fifth week was spent under the Goat-herd’s Banyan tree (Ajapāla) and while there he reflected on his abandonment of the austere practices:- “Delivered am I from the austere practices that cause physical pain and suffering. It is well that I’m delivered of that unprofitable practice of austerity. How delightful it is to be liberated and have gained Enlightenment.”

Māra, who had been closely following every thought and action of the Bodhisatta, ever alert to accuse him of any lapses, immediately addressed the Buddha, “Apart from the austere practices, there is no way to purify beings; Gotama has deviated from the path of purity. While still defiled, he wrongly believes that he has achieved purity.”

The Buddha replied, “All the extreme practices of austerity employed with a view to achieve the deathless are useless, unprofitable much as oars, paddles, and pushing poles are useless on sand banks. Fully convinced that they are unprofitable, I have abandoned all forms of self-mortification (attakilamathānuyoga).”

The Commentary also mentions that extreme practices such as fasting or nakedness constitute self-mortification. That extreme austerity is a form of self-mortification should be carefully noted here for better comprehension of the Dhammacakka Sutta when we deal with it.

Considering to Whom to Give the First Discourse

Having spent seven days each at seven different places, he went back to the Goat-herd’s Banyan tree on the fiftieth day. Seated under the tree, he considered, “To whom should I first teach the Dhamma? Who would quickly comprehend it?” Then it occurred to him, “There is Āḷāra Kālāma who is learned, intelligent, and wise. He has long been a person with little dust of defilement in his eye of wisdom. If I teach the doctrine to Āḷāra Kālāma first he would quickly comprehend this Dhamma.

It is significant that the Buddha tried to seek out someone who would understand his teaching quickly. It is vital to inaugurate new meditation centres with devotees who are endowed with faith, energy, energy, mindfulness, and wisdom. Only such devotees as possess these virtues can achieve insight quickly and become shining examples for others to follow. Devotees lacking ability or enfeebled in mind and body through age can hardly be a source of inspiration to others. When I first started teaching Satipaṭṭhāna Vipassanā Meditation, I was fortunate in being able to start with three persons (my relatives actually) endowed with exceptional faculties. They acquired the knowledge of arising and passing away (udayabbaya-ñāṇa) within three days of practice and were overjoyed with seeing lights and visions accompanied by feelings of rapture and bliss. Such speedy attainment of results has been responsible for the world-wide dissemination of the Mahāsi Vipassanā Meditation technique.

Thus the Buddha thought of first teaching someone who would quickly grasp it. When he considered Āḷāra Kālāma, a deity addressed him, “Venerable sir, Āḷāra Kālāma passed away seven days ago.” Then knowledge and vision arose to the Buddha that Āḷāra had indeed passed away seven days ago and had by virtue of his jhānic achievements reached the realm of nothingness, (ākiñcaññāyatana).

Missing the Path and Fruition by Seven Days

“Great is the loss to Āḷāra the Kālāma,” thought the Buddha. Āḷāra was developed enough to readily understand. Had he heard the teaching he could have gained the Path and attained Arahantship instantly. However, his early death has deprived him of this opportunity. In the realm of nothingness, where only mental states exist without any forms, he could not benefit even if the Buddha had gone there and taught him the Dhamma. The life-span in the realm of nothingness is also very long being sixty thousand aeons. After expiring there, he would be reborn in the human realm, but would miss the teachings of the Buddha. Thus as a common worldling, he would remain in the cycles of existence, sometimes sinking to the nether world to face great sufferings. Thus the Buddha saw that the loss to Āḷāra was very great.

It is possible in present times that there are people deserving of higher attainments, passing away without the opportunity of hearing about the Satipaṭṭhāna meditation method, or though having heard it taught, who have not yet made the effort to practise it. The good people assembled here now listening to what I am teaching should be careful that a rare opportunity for their spiritual development is not wasted.

Missing the Great Chance by One Night

Then the Buddha thought of teaching the first discourse to Udaka, the son (pupil) of the great sage Rāma. Again a deity addressed the Buddha, “Venerable sir, Udaka Rāmaputta passed away last night.” Knowledge and vision arose to the Buddha that the hermit Udaka had indeed died last night in the first watch and by virtue of his jhānic achievements had reached the realm of neither perception nor non-perception, (nevasaññānāsaññāyatana). This realm is also a state of immateriality, a formless state and its life-span extends to eighty-four thousand world cycles. This is the noblest, the loftiest of the thirty-one planes of existence, but the Dhamma cannot be heard there. On appearing again in the human world, Rāmaputta was already so highly developed that he could instantly attain Arahantship if he could but listen to the Dhamma. However, he would get no such opportunity, having missed it by dying one night too early. The Buddha was thus moved again to utter in pity, “Great is the loss to the hermit Udaka, the son (pupil) of the great sage Rāma.”

The Buddha thought again to whom he should give his first discourse. The group of five ascetics appeared in his divine vision and he saw them living then in the deer sanctuary in the township of Benares.

Journey to Give the First Sermon

The Blessed One set out to go there. Some previous Enlightened Ones had made the same journey by means of psychic powers. However, our Buddha, Gotama, proceeded on foot for the purpose of meeting, on the way, the naked ascetic Upaka to whom he had something to impart.

The Buddhavaṃsa and Jātaka Commentaries state that the Blessed One started the journey on the full-moon of July. However, as the deer sanctuary, Benares, was eighteen leagues (yojana) or about 144 miles away from the Bodhi tree and as the Blessed One was making the journey on foot, the distance could not have been covered in one day unless done with the help of psychic powers. It would be appropriate, therefore, if we fixed the starting date on the sixth waxing of July.

Meeting Upaka the Naked Ascetic

The Blessed One had not gone far from the Bodhi Tree on the way to Gāyā (6 miles) when he came upon the naked ascetic Upaka, a disciple of the naked ascetic Nigaṇṭha Nāṭaputta. On seeing the Blessed One he addressed him, “Your countenance friend, is clear and serene, your complexion is pure and bright, in whose name have you gone forth? Who is your teacher? Whose teaching do you profess?” The Blessed One replied:-

“Sabbābhibhū sabbavidūhamasmi,

sabbesu dhammesu anūpalitto.

Sabbañjaho taṇhākkhaye vimutto,

sayaṃ abhiññāya kamuddiseyyaṃ.”

“I am one who has overcome all,¹⁵

One who knows all, I am detached from all things;

Having obtained emancipation by the destruction of desire.

Having by myself gained knowledge.

Whom should I call my master?”

The Blessed One made known his status more emphatically as follows:-

“Na me ācariyo atthi, sadiso me na vijjati.

Sadevakasmiṃ lokasmiṃ, natthi me paṭipuggalo.”

“I have no teacher, one like does not exist,

In the world of men and gods, none is my counterpart.”

Upon this Upaka wondered whether the Blessed One had gained Arahantship. The Buddha replied:-

“Ahañhi arahā loke, ahaṃ satthā anuttaro.

Ekomhi sammāsambuddho, sītibhūtosmi nibbuto.”

“I, indeed, am the Arahant in the world.

A teacher with no peer,

The sole Buddha, Supreme, Enlightened.

All passions extinguished, I have gained the peace of nibbāna.”

Upaka then asked the Blessed One where he was going, and on what purpose.

“Dhammacakkaṃ pavattetuṃ, gacchāmi kāsinaṃ puraṃ.

Andhībhūtasmiṃ lokasmiṃ, āhañchaṃ amatadundubhi”nti.

“To set in motion the Wheel of Dhamma,

I go to the town of Kāsi (Benares).

In the world of blind beings,

I will beat the drum of the Deathless.”

Upon this Upaka asked:- “By the way in which you profess yourself are you worthy to be called an infinite conqueror (anantajino)?” The Buddha replied:-

“Mādisā ve jinā honti, ye pattā āsavakkhayaṃ.

Jitā me pāpakā dhammā, tasmāhamupaka jino”ti.

“Those are conquerors who, like me, have reached the extinction of cankers. I have vanquished all thoughts, ideas, and notions of evil (sinfulness). For that reason, Upaka, I am a conqueror, a victorious one.” ¹⁶

Upaka belonged to a sect of naked ascetics under the leadership of Nāṭaputta who was addressed by his disciples as “The Conqueror.” The Blessed One in his reply was explaining that only those who have really extinguished the cankers, eradicated the defilements, like him, are entitled to be called a conqueror.

Truth Is Not Seen if Blinded by Misconception

After this declaration by the Blessed One that he was truly an infinite conqueror, the naked ascetic Upaka muttered, “It may be so, friend,” shook his head, and giving way to the Blessed One continued his journey.

It is important to note carefully this event of Upaka’s meeting with the Buddha. Here was Upaka coming face to face with a Fully Enlightened Buddha, but he did not realise it. Even when the Blessed One openly declared that he was indeed a Buddha, Upaka remained sceptical because he was holding fast to the wrong-views of the naked ascetics. In these days too there are people who, following wrong paths, refuse to believe when they hear about the right method of practice. They show disrespect to, and talk disparagingly about, those practising and teaching the right method. Such misjudgements arising out of false beliefs should be carefully avoided.

Even though he did not express complete acceptance of what the Buddha said, Upaka seems to have departed with some faith in the Buddha, as he returned after some time. After leaving the Buddha, he later got married to Cāpā, a hunter’s daughter, and when a son was born of the marriage, he wearied of the household life and became a recluse under the Blessed One. Practising the Buddha’s teaching, he became a Once-returner (anāgāmi). On passing away he reached the Pure Abode of Avihā, where he soon attained Arahantship. Foreseeing this beneficial result that would accrue out of his meeting with Upaka, the Blessed One set out on foot on the long journey to Benares and answered all of the questions asked by Upaka.

Arrival at Isipatana

When the group of five ascetics saw the Blessed One at a distance coming towards them, they made an agreement among themselves saying, “Friends, here comes the monk Gotama who has become self-indulgent, who has given up the struggle, and reverted to a life of luxury; let us not pay homage to him, nor greet him, and relieve him of his bowl and robes. However, as he is of noble birth, we will prepare a seat for him. He will sit down if he is so inclined.”

However, as the Blessed One drew near, because of his illustrious glory, they found themselves unable to keep to their agreement. One went to greet him and receive the bowl, a second took his robe, a third prepared a seat for him, a fourth brought water to wash his feet, while the fifth arranged a foot stool. However, they all regarded the Blessed One as their equal and addressed him as before by his name Gotama and irreverently with the appellation “Friend (āvuso).” The Blessed One sat on the prepared seat and spoke to them.

“Monks, do not address me by name as Gotama nor as friend. I have become a Perfect One, worthy of the greatest reverence. Supremely accomplished like the Buddhas of former times, and Fully Enlightened. Listen, monks! The Deathless has been gained, the Immortal has been won by me. I will teach you the Dhamma. If you practise as instructed by me, in no long time, in the present life, you will, through your own direct knowledge, realise, enter upon, and abide in Arahantship, the ultimate and noblest goal of the holy life for the sake of which clansmen of good families go forth from household life into homelessness.”

Even with this bold assurance, the group of five monks remained incredulous and retorted: “Friend Gotama, even with the abstemious habits and stern austerities that you practised before, you did not achieve anything beyond the attainments of ordinary men nor attain the sublime knowledge and insight of the Noble Ones, which alone can destroy the defilements. Now that you have abandoned the austere practices and are working for gains and benefits, how will you have attained such distinction, such higher knowledge?”

This is something to ponder. These five monks were formerly court astrologers who were fully convinced and had foretold, soon after his birth, that the Bodhisatta would definitely attain Supreme Enlightenment. However, when the Bodhisatta gave up privations and stern exertions, they wrongly thought that Buddhahood was no longer possible. It could be said that they no longer believed in their own prophecy. They remained incredulous now that the Blessed One declared unequivocally that he had won the Deathless, had become a Fully Enlightened One, because they held to the wrong notion that extreme austerity was the right way to Enlightenment. Likewise, nowadays, too, once a wrong notion has been entertained, people hold fast to it and no amount of explaining the truth will sway them and make them believe. They even turn against those who try to bring them to the right path and speak irreverently and disparagingly of their well-wishers. One should avoid such errors and self-deception.

With great compassion for the group of five monks the Blessed One spoke to them thus:- “Monks, the Perfect One, like those of former times, is not working for worldly gains, he has not given up the struggle, nor abandoned the true path that eradicates the defilements; he has not reverted to luxury,”and declared again that he had become a Perfect One, worthy of great reverence, supremely accomplished and Fully Enlightened. He urged them again to listen to him.

A second time, the group of five monks made the same retort; and the Blessed One, realising that they were still suffering from illusion and ignorance, and out of great pity for them gave them the same answer for the third time.

When the group of five monks persisted in making the same remonstrations, the Blessed One spoke thus, “Monks, ponder upon this. You and I are not strangers, we lived together for six years and you waited on me while I was practising extreme austerities. Have you ever known me speak like this?” The five monks reflected on this. They came to realise that he had not spoken thus before because he had not attained Higher Knowledge then. They began to believe that he must have acquired the Supreme Knowledge now to speak to them thus. They replied respectfully, “No. venerable sir (bhante), we have not known you speak like this before.”

Then the Buddha said, “Monks, I have become a Perfect One worthy of the greatest respect (Arahaṃ), supremely accomplished like the Buddhas of former times (Tathāgata) by my own effort I have become Fully Enlightened (Sammāsambuddha), I have gained the Immortal, the Deathless (amatamadhigataṃ). Listen, monks, I will instruct you and teach you the Dhamma. If you practise as instructed by me, you will in no time and in the present life, through your own direct knowledge, realise, enter upon, and abide in Arahantship, the ultimate and the noblest goal of the holy life for the sake of which clansmen of good families go forth from the household life into homelessness.” Thus the Blessed One assured them again.

The five monks became receptive and prepared to listen respectfully to what the Buddha would say. They awaited with eagerness to receive the knowledge to be imparted to them by the Blessed One.

What we have stated so far constitutes events selected from the second type of introduction, from the intermediate period. We now come to events of the recent past, introduced with the words, “Thus have I heard,” which gives an account of how the Blessed One began to set in motion the Wheel of Dhamma by giving the first discourse.

The time was the evening of the full moon of May 2,551 years ago counting back from this year of 1962. The sun was about to set, but still visible as a bright, red sphere; the bright full-moon was rising in the East. The Commentary on the Dhammacakka Sutta in the Saṃyuttanikāya mentions that the first discourse was given while both the sun and the moon were simultaneously visible in the sky.¹⁷

The audience consisted of only the five monks from the human world. However, there were 180 million brahmās, and innumerable deities, according to the Milindapañha. Thus when the five monks together with brahmās and deities, who were fortunate enough to hear the first discourse, were respectfully awaiting with rapt attention the Blessed One began teaching the Dhammacakka sutta with the words: “Dve me, bhikkhave, antā pabbajitena na sevitabbā.”

“Monks, one who has gone forth from the worldly life should not indulge in these two extreme parts.”

Here, “antā,” according to the Commentarial interpretations, connotes grammatically “koṭṭhāsa” or “bhāga,” which means a share or portion of things. However, in view of the doctrine of the Middle Path taught later in the discourse, it is appropriate to render “antā” as extreme. Again “Part or portion of things” should not be taken as any part or portion of things, but only those parts that lie on the two extremes. Hence our translation as two extreme parts. The Sinhalese and Siamese Commentaries render it as “Lammaka Koṭṭhāsa” meaning “bad part,” which is somewhat similar to the old Burmese translation of “bad thing or practice.” Thus it should be noted first that one who has gone forth from the worldly life should not indulge in two extreme parts or practices.

“Katame dve? Yo cāyaṃ kāmesu kāmasukhallikānuyogo hīno gammo pothujjaniko anariyo anatthasaṃhito, yo cāyaṃ attakilamathānuyogo dukkho anariyo anatthasaṃhito.”

“What are the two extreme practices? Delighting in desirable sense-objects, one pursues sensual pleasure, makes efforts to produce such pleasures and enjoys them. This extreme practice is inferior; vulgar, being the habit of villagers; common and worldly, being indulged in by ordinary individuals; ignoble, hence not pursued by the Noble Ones; profitless and not pertaining to one’s true welfare. Such pursuit of sensual pleasures is one extreme practice to be avoided.”

Pleasurable sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and touches constitute desirable sense-objects. Taking delight in such objects and enjoying them physically and mentally, one pursues sensual pleasures. This practice, which forms one extreme practise, is low, vulgar, common, ignoble, and unprofitable. It should, therefore, not be followed by one who has gone forth from household life.

The other extreme practice is concerned with inflicting torture on oneself, which can result only in suffering. Abstaining from food and clothing, which one is normally used to, is a form of self-mortification and is unprofitable. Being ignoble, this practice is not pursued by the Noble Ones. Neither does it pertain to one’s true welfare. Thus the practice of self-mortification, being another extreme practice, should also be avoided. Avoiding these two extremes, one arrives at the true path known as the Middle Path. Thus the Blessed One continued:–

“Ete kho, bhikkhave, ubho ante anupagamma, majjhimā paṭipadā Tathāgatena abhisambuddhā, cakkhukaraṇī ñāṇakaraṇī upasamāya abhiññāya sambodhāya nibbānāya saṃvattati.”

“Bhikkhus, avoiding these two extreme practices, the Tathāgata has gained the higher knowledge of the Middle Path, which produces vision and knowledge, leads to tranquillity (the stilling of defilements), to higher knowledge, and nibbāna (the end of all suffering).”

Avoiding these two extremes, by rejecting wrong paths, the Middle Path is reached. By following this true path, Enlightenment is gained, and nibbāna realised.

How the Middle Path, which is also known as the Noble Eightfold Path, produces vision and knowledge, and how it leads to tranquillity and Enlightenment will be dealt with in my discourse next week.

May all good people present in this audience, by virtue of having given respectful attention to this Great Discourse on the Turning of the Wheel of Dhamma, with its introductions, be able to avoid the wrong path, namely, the two extremes and follow the Noble Eightfold Path, thereby gaining vision and higher knowledge which will soon lead to the realisation of nibbāna, the end of all suffering.

Sādhu! Sādhu! Sādhu!

Part Two

Part Two

Delivered on Saturday, 6th October, 1962.¹⁸

This discourse was delivered beginning on the new-moon of September. The introduction to the discourse took most of my time on that occasion. I could deal only with the opening lines of the Sutta. Today I will pick up the thread from there.

Avoiding the Two Extremes

“Dveme, bhikkhave, antā pabbajitena na sevitabbā.”

“Monks, these two extreme practices should not be followed by one who has gone forth from household life.”

Why shouldn’t they be followed? Because the main purpose of one who has gone forth from household life is to rid himself of defilements such as lust and anger. This objective could not be achieved by indulging in these two extreme practices, because they will tend to promote further accumulations of lust and anger.

What are the two extreme practices? Delighting in desirable sense-objects, pursuing and enjoying sensual pleasures constitutes one extreme practice. This practice is inferior; vulgar, being the habit of villagers; common and worldly, being indulged in by ordinary individuals; ignoble, hence not pursued by the Noble Ones; profitless and not pertaining to one’s true welfare. Such pursuit of sensual pleasures is an extreme practice that should be avoided.

There are five kinds of desirable sense-objects: namely pleasurable sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and touches; in brief, all the material objects, animate or inanimate, enjoyed by people in the world. Delighting in a seemingly pleasurable sight and enjoying it constitute the practice and pursuit of sensuality. Here the sense-object of sight means not merely a source of light or colour that comes into contact with the eye, but the man, woman, or the whole of the object that forms the source or origin of that sight. Similarly all sources of sound, smell, and touch, whether a man, woman, or material objects constitute sensual objects. As regards taste, not only the various foods, fruits, and delicacies, but also men and women who prepare and serve them are classified as objects of taste. Listening to a pleasant sound, smelling a fragrant smell are as sensual as enjoyment of good, delicious food, the luxury of a comfortable bed or physical contact with the opposite sex.

Sensual Indulgence Is Inferior and Vulgar

Delighting in sensual pleasures and relishing them is regarded as a vulgar practice because such enjoyments lead to the formation of base desires, which are clinging and lustful. It promotes conceit, with the thought that no one else is in a position to enjoy such pleasures. At the same time one becomes oppressed with thoughts of avarice, not wishing to share the good fortune with others, or overcome by thoughts of jealousy or envy, i.e. wishing to deny similar pleasures to others.

It arouses ill-will towards those who are thought to be opposed to oneself. Flushed with success and affluence, one becomes shameless and unscrupulous, bold and reckless in one’s behaviour, no longer afraid to do evils. One begins to deceive oneself, with the delusion (moha) of well-being and prosperity. The uninformed worldling (puthujjana) may also come to hold a wrong-view of a living soul (atta) or entertain disbelief in the effects of one’s own actions. Since these are the outcome of delighting in and relishing sensual pleasures, they are regarded as inferior and vulgar.

Furthermore, indulgence in sensual pleasures is the habitual practice of lower forms of beings such as animals or hungry ghosts. Bhikkhus and recluses, who belong to a higher class of existence should not stoop so low as lower forms of life in the vulgar practice of base sensuality.

The pursuit of sensual pleasures does not lie within the province of one who has gone forth. It is the concern of the town and village folks, who regard sensual pleasures as the greatest bliss; the greater the pleasures, the greater the happiness. In ancient times, rulers and wealthy people engaged in the pursuit of sensual pleasures. Wars were waged and violent conquests made, all for the gratification of sense-desires.

In modern times too, similar conquests are still being made, in some areas, for the same objectives. However, it is not only the rulers and the wealthy who seek sensual pleasures; the poor are also ardent in the pursuit of worldly goods and pleasures. In fact, as soon as adolescence is reached, the instinct for mating and sexual gratification makes itself felt. For the householder who is oblivious to the Buddha’s teaching, the gratification of sense desires appears to be the pinnacle of happiness and enjoyment.

The Doctrine of Ultimate Bliss in This Very Life

Even before the time of the Buddha, there were people who held the belief that heavenly bliss could be enjoyed in this very life. (diṭṭhadhamma nibbāna vāda). According to them, sensual pleasure was blissful, and there was nothing to surpass it. Sensual pleasure was to be enjoyed in this very life. It would be foolish to let precious moments for enjoyment pass, waiting for bliss in a future life, which does not exist. The time for full gratification of sensual pleasure is in this very life. Such is the belief of diṭṭhadhamma nibbāna vāda. This is one of the sixty-two wrong-views expounded by the Buddha in the Brahmajāla Sutta, the first discourse of the Dīghanikāya.